Jerusalem in Brief (No. 1)

An Iron Age Moat on the Southeastern Hill, 19th-century photograph, and summaries of other sources about historical Jerusalem

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

This is the first post in a new series arriving the second Friday of every month titled “Jerusalem in Brief.” The goal is to engage selected media about historical Jerusalem in shorter summaries rather than devoting an entire post to one issue. Below I summarize a recent article (“New article summary”), describe some details of a historical photograph (“Jerusalem visualized”), and list a few other items of note. Future posts in this series will look similar, though some categories will change month to month.

New article summary

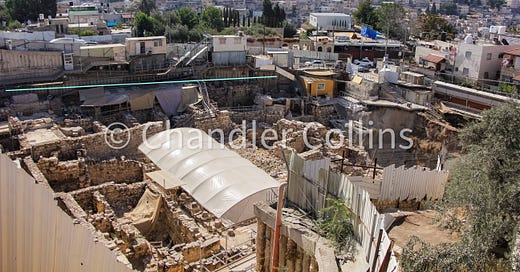

I recently listed a number of new publications about historical Jerusalem. An important article appears on this list that has also been highlighted widely in popular media: “An Early Iron Age Moat in Jerusalem between the Ophel and the Southeastern Ridge/City of David” by Yuval Gadot, Efrat Bocher, Liora Freud, and Yiftah Shalev. It was published open access in the latest issue of Tel Aviv, so you can read it and peruse the excellent maps and illustrations. The article highlights findings in the Givati Parking Lot Excavations which are located southeast of Dung Gate in the Silwan neighborhood of Jerusalem on the western slope of the Southeastern Hill. Below I’ll briefly summarize the contents of the article.

What does this article discuss?

The article presents a significant and unexpected drop (around 9 m.) in the bedrock that was exposed along the far eastern side of the Givati Parking Lot Excavations. This drop in the bedrock is understood to be evidence of a moat with two opposite scarps. The southern scarp is quite steep, while the northern scarp is more gradual and cut in steps (pgs. 153-155).

How are these finds interpreted?

The authors argue that the drop in bedrock constitutes an intentionally cut moat which they estimate was ~30 m. wide, ~6-9 m. deep, and ~75 m. long (pg. 162). The article presents only the far western profile of this moat which was exposed where the Southeastern Hill begins to slope downward toward the Central Valley. By combining data from this excavation with other more limited digs that took place on top of the hill, the authors make a case that the moat stretched across the entire width of the hill to the Kidron Valley in the east (pgs. 160-162). They describe it as a major defensive project involving the removal of ~13,000 cubic meters of rock and argue that it functioned to separate the Southeastern Hill from the ridge to the north (pgs. 162-163).

(an earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the moat was estimated to be ~30 m. deep and ~6-9 m. wide)

Date of the moat

The latest period in which the moat could have been cut (terminus ante quem) can be inferred from finds in and around it. A wall dated to the Persian Period was built into the southern scarp of the ditch, indicating that at least this side must have been cut before that time (pg. 155). The stepped northern scarp contains a horizontal segment of bedrock with several interesting rock-cut channels (Installation 7744).1 Soil inside the channels and sealed above by later deposits contained pottery from the late 9th/early 8th centuries BCE (Iron Age IIA). Other walls and buildings from the Iron Age II were also found to the west of the moat, built against its mouth. For these reasons, the excavators argue that the moat must have been cut during the Late Iron Age IIA or sometime before (pg. 160). This could apparently include any date starting in the mid-9th century BCE and going backward in time (pg. 163).

Purpose of the moat

The authors do not wager a guess at the initial reasons the moat was cut but suggest that it probably served to separate the Southeastern Hill to the south and the Ophel to the north during the 9th and 8th centuries BCE (pgs. 163-166). They leave open the possibility that the moat may have served as part of city’s northern defenses during the time of the Canaanites (Middle Bronze Age), though they think it is unlikely (pg. 165).

Critical questions

The full profile of the moat was revealed only on its far western edge where the topography slopes westward toward the Central Valley. However, we do not know much about the character of the moat on top of the hill other than that it seems to have existed. Is it as dramatically and intentionally shaped here as it is in the portion unearthed in the Givati Parking Lot? Or is it simply a more gentle dip and rise in the topography here, perhaps occasioned by pre-existing gullies formed by erosion (as suggested by Margreet Steiner; pg. 162)? This would have a bearing on our interpretation of its function and its effectiveness as a defensive barrier.

Scholarly context

As mentioned in the article’s introduction, these findings are presented in an interesting context (pgs. 147-149). Most scholars hold that the ancient core of Jerusalem was founded near the perennial spring (south of the moat). However, over the past few decades, some scholars have argued that the original city of Jerusalem stood instead on the higher ground to the north of the moat (the Ophel and Noble Sanctuary/Temple Mount area). As the authors mention in the article, it is tempting to view this moat as the northern barrier of Jerusalem, as it would fit nicely with the prevailing opinion for the ancient city’s location (pgs. 165-166). Following the conversation around the moat will be interesting. As far as I am aware, no responses have yet been published, but I am sure that they will be. The excavators also have not reached the bottom of the moat yet, so the data and their interpretations may change in the future.

Jerusalem visualized

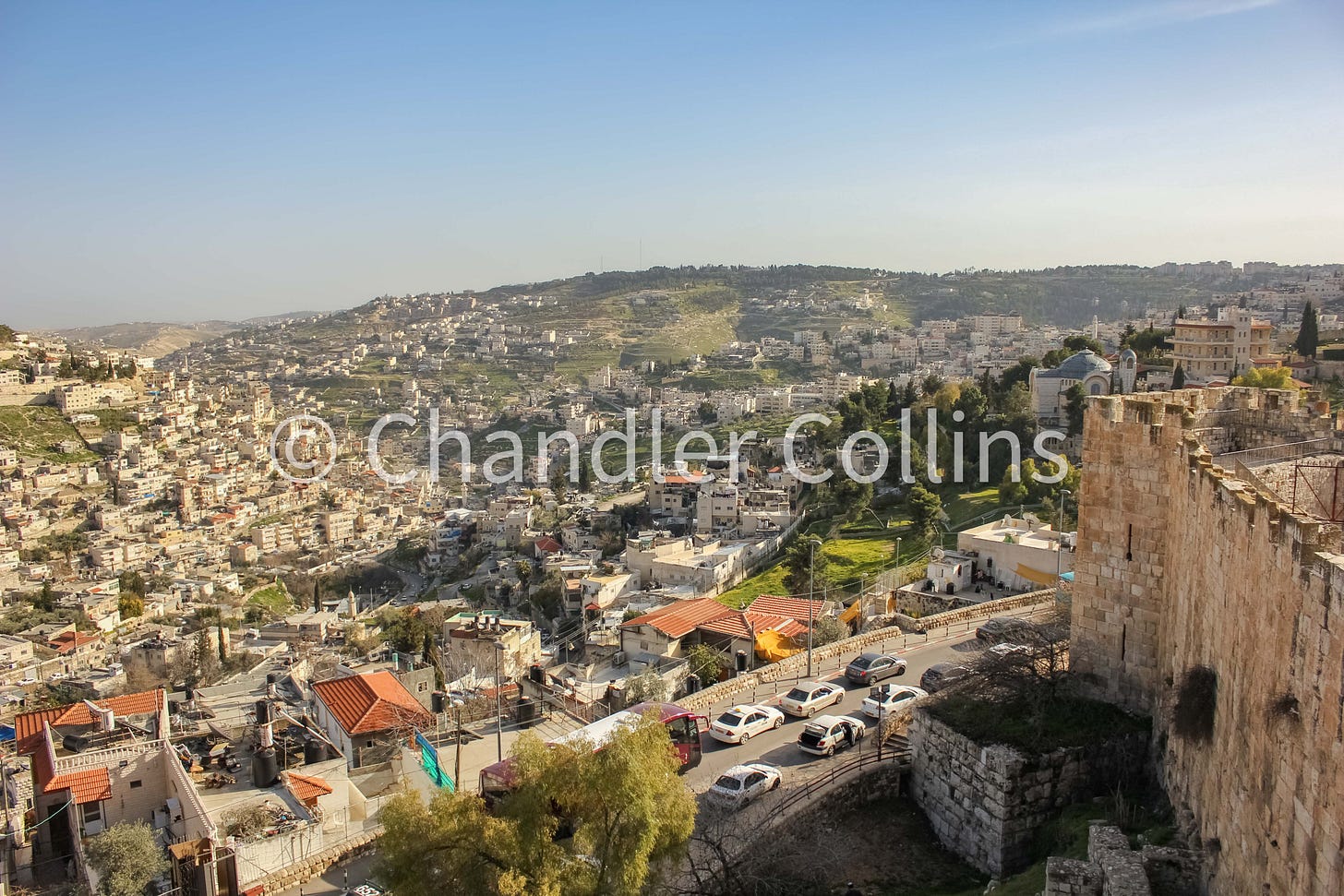

The photograph above was taken by Félix Bonfils sometime between 1867-1885. It looks to the south from the top of Jerusalem’s walls. A clipping of the wall visible on the right terminates in a projecting tower known as Burj al-Kibryt (“the Sulphur Tower”). A dirt path runs along the bottom of the walls below. Today this area has been excavated and contains ruins from many different periods that can be seen while walking between Zion and Dung Gate (Ben-Dov 1994:311-320).

This photo illustrates that until very recently Jerusalem was surrounded only by its immediate hinterland, as it had been for its entire history. Despite the lack of buildings in the photo, virtually all the immediate terrain has been carefully marked into agricultural plots which were owned and managed by locals. The photo suggests a variety of annual and perennial crops, such as the easily detectible olive trees. Several decades after this photo was taken, R. A. S. Macalister negotiated a rental contract to excavate a cauliflower plot just off this photo to the left. The Givati Parking Lot Excavation discussed in the article summary above is located in the same area.

Perhaps the most interesting features in the photo are center left, shown in the closeup view above. Two buildings circled in orange stand in the southern confluence of Jerusalem’s valley systems and mark the location of a water source known in Arabic as Bir Ayyub (“well of the fuller”). Contemporary writers described this well overflowing during the rainy season, providing drinking water and a convenient place to do laundry. Most scholars believe this was the location of the ancient water source referred to as En Rogel in the Hebrew Bible (Joshua 15:7; I Kings 1:9). Today Bir Ayyub is enshrined in a mosque.

A conspicuous depression called Birkat al-Ḥamra (“the red pool”) sits a little northeast of Bir Ayyub (marked with a green dot). A large mulberry tree circled in blue growing on the southeastern side of the pool was remembered in popular tradition as the location where the Prophet Isaiah was martyred. A bedrock outcropping sits left of the dam wall and marks the southern tip of the Southeastern Hill. Excavations in 2004 by Ronny Reich and Eli Shukron under this outcropping revealed the steps of a large pool from the Roman Period interpreted by them as the Pool of Siloam. New excavations begun in late 2022 in this area are the subject of some controversy.

All in all, the photo shows a very interesting and somewhat unique view of Jerusalem during the Late Ottoman Period. One of my recent photos is below for comparison.

Notes & quotes

Many western travelers who arrived in Jerusalem during the 19th century expressed a sense of disappointment when they first saw the city. This probably happened for many reasons, but one was their tendency to compare Jerusalem to the world’s largest urban centers where they lived or had traveled through. His own biases notwithstanding, Claude Reignier Conder’s comment below should have been required reading:

“Let like be compared with like, and not with that which is incommensurate. Compare Jerusalem with Paris or London…the result will naturally be unfavourable to scenery which is on a smaller scale ; but when, after seeing the shapeless and half-ruined villages near Jaffa, the well-built walls, the fine buildings, the battlements, archways, pillars, palms, and gardens of the capital strike the eye, the effect is certainly superior in beauty to moderate expectations.” (PEFQS 1872:155)

Upcoming (digital) events

The Yad Ben Zvi Institute is hosting two virtual lectures on aspects of Jerusalem next week which will be given in Hebrew:

14 January 2024 18:00-19:00 (JT)/11:00 AM-12:00 PM (ET) - The conquest of Jerusalem in the Bible. Register here.

15 January 2024 17:00-18:30 (JT)/10:00-11:30 AM (ET) - Beit Hamidot - a magnificent residential building from the time of the Second Temple in the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem - summary of the findings with the publication of the final report by Hillel Geva with Ronny Reich as commentator. Register here.

Paid subscribers

The next livestream for paid subscribers will take place on March 5 from 8:00-9:30 PM ET. Among other things, we’ll discuss the newest excavations at the Holy Sepulcher.

Take a look at the interactive bibliography of Jerusalem for some new items that were listed this week.

Are you having issues accessing your subscriber benefits? Reply to this email or contact me at approachingjerusalem@gmail.com to let me know.

Another set of rock-cut channels (Installation 7702) was found outside the ditch and north of it. These are the “mysterious” channels that were picked up recently in popular media. The authors argue that they were “smoothed by liquid” (pg. 155) and used for soaking an unknown product, rather than for quarrying (pg. 156).

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous posts from this newsletter and follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.