Jerusalem in Brief (No. 5)

A new radiocarbon study of Jerusalem and a model showing Herod the Great's three towers

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription and receive unique Jerusalem-related benefits.

New article analysis

A mammoth radiocarbon study, “Radiocarbon chronology of Iron Age Jerusalem reveals calibration offsets and architectural developments” was published two weeks ago in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA (PNAS). Shortly thereafter, popular media outlets began covering the article with headlines heralding the new chronology. An 84-page supplement was published alongside the relatively concise article (12 pages). The supplement provides details for the context of each organic sample taken from the field for testing along with other information.

What does this article discuss?

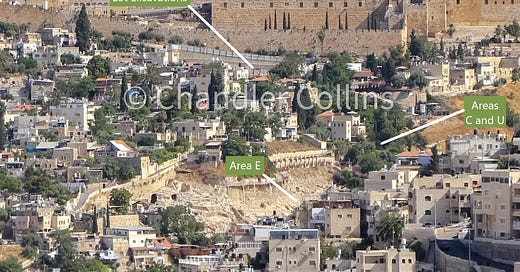

This article presents the first major radiocarbon study of Iron Age Jerusalem, discussing the results of 103 radiocarbon dates acquired from five excavation areas. These excavations are all found on the slopes of the Southeastern Hill. Two areas are located in the Givati Parking Lot on the hill’s northwestern slopes, and three areas sit on its southeastern slopes near Jerusalem’s perennial spring (Areas U, C, and Yigal Shiloh’s Area E). There are many components of the study, which I will try my best to summarize below.

Many radiocarbon dates discussed in this study fall within the Hallstatt Plateau, a period from ~770-420 BCE when Carbon-14 was not formed at consistent rates in Earth’s atmosphere (3). This situation complicates the ability of researchers to ascertain radiocarbon dates during a period which is crucial for Jerusalem’s history. The study aimed to overcome this problem by first carefully retrieving a large amount of radiocarbon samples from secure contexts and then setting them alongside additional chronological information—such as data derived from dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) or destruction uncovered from the secure 586 BCE context of the Babylonian assault on Jerusalem—in order to narrow the scope of the possible dates for each sample. This study was able to pinpoint two local radiocarbon “offsets,” time periods during which solar activity seems to have generated unexpected amounts of Carbon-14 in the Southern Levant or perhaps specifically in the Jerusalem area (9-10). This is a major achievement that can help correct the calibration curve for future radiocarbon studies.

Perhaps the most interesting archaeological context presented in this study comes from a room (Room 17063) of an Iron Age II building in Area U, located just above the spring. The room contained a series of 11 floors constructed one upon another, all dating to the 8th-7th centuries BCE. The floors yielded pottery and other remains. It is unique to find such a sequence in Jerusalem during this time, as the building projects of later periods often sunk their foundations to bedrock and disturbed earlier ones. Additionally, because Iron Age II Jerusalem escaped widespread destruction until the very end of the period, structures in the city stood undisturbed for a long time. This was the case, for instance, with Building 100 in the Givati Parking Lot which features in this study (8-9). In such structures, floors could simply be cleared and reused for decades or even hundreds of years, leaving archaeologists without much material to find apart from what was left when they were finally destroyed.

Organic samples were taken from each of the 11 floors of the Area U room and dated, demonstrating that the building was used continuously for about 100 years, from ~760 BCE until the mid-7th century (3). The article assigns dates within a few decades to each floor and discusses pottery vessels that were found on them. Some pottery types were uncovered on only one or several of the floors, suggesting that they may have been in use for short time periods. This could potentially help archaeologists date contexts where similar vessels have been found in Jerusalem or at other sites. The authors note that this is a “first step in improving the ceramic dating” in Jerusalem, recognizing the possibility that the pottery forms they encountered on these floors may simply be accidental due to the small size of the room (4). Hopefully, future work can build on their initial observations.

The study also contributes to questions about Jerusalem’s chronology during other parts of the Iron Age. Some organic material from excavations on the Southeastern Hill yielded early radiocarbon dates that fell between the 12th-10th centuries BCE (4-5). There are not many architectural remains known in Jerusalem from this time period. However, the presence of organic material suggests that a population may have existed then, even if buildings constructed by them did not survive (though this is just one possible interpretation). Other samples demonstrate that construction projects took place on both slopes of the Southeastern Hill during the 9th century BCE (8).

This article also presents evidence of destruction in several areas which the authors interpret as the result of a mid-8th century BCE earthquake. They believe this is the same earthquake mentioned in Amos 1:1 (8) and consider it to be a chronological anchor in their study (2). The key location for this destruction is found in a room of a building in Area U (Room 17130) which contained storage jars and the skeleton of a piglet(!) that were covered by collapsed stones and debris (8). A large fortification wall built east of this room, and usually associated with the building projects of King Hezekiah, is understood as part of the renovations that took place after the earthquake transpired.

While the topic of the paper is focused on questions of chronology, the wide array of archaeobotanical remains retrieved in the field is not to be missed. These include at least: barley, wheat, grape, olive, lentil, almond, smilax, pea, linen, wild vetch, sycamore fig, carob, oak, and pomoidaea.

How are these finds interpreted?

The study’s conclusions argue that we should push Jerusalem’s chronology backward in time. The authors believe their findings support the views that:

there was a “widespread occupation of yet undetermined character” during the 12th-10th centuries BCE (5)

fortification efforts typically associated with Hezekiah should now be bumped decades earlier and attributed to Uzziah (10)

urban expansion out of Jerusalem’s ancient core began in the 9th century BCE (8).

The location of the excavation areas discussed in the study demonstrate that this growth occurred on both the eastern and western slopes of the Southeastern Hill, but the tenor of the paper mainly evokes Jerusalem’s expansion onto the Western Hill. The date when this occurred has been the topic of some debate over the last 70+ years. Scholars have dated the Western Hill settlement within a 100-year time period ranging from the end of the 9th century to the end of the 8th century BCE. The mid-8th century BCE is the commonly accepted date for the beginning of the settlement on the Western Hill. The article under review here does not attempt to assign a firm date to the settlement on the Western Hill, but it implies that it may have begun as early as the 9th century BCE. Building 100 in the Givati Parking Lot is the major locus of evidence for this, as it represents—in the view of the authors—the beginning of “the city’s westward spread out of its ancient core” (10).

Critical questions

The many components presented in this article deserve serious thought and consideration that is simply not possible in this short venue. However, I will consider one issue critically here, which in no way intends to detract from this impressive body of work. The argument that Jerusalem’s westward growth began during the 9th century BCE must be tempered by the distance between the new Iron Age settlement on Western Hill and the excavation areas discussed in the article, which are located on the Southeastern Hill. Building 100, the farthest west of these Iron Age II buildings, sits quite a distance from the modern Jewish Quarter where evidence of an Iron Age settlement was uncovered in Nahman Avigad’s salvage excavations after 1967. The top of modern Mount Zion, where the Iron Age settlement also existed, is located even farther away. How should we understand the relationship between this expansive new settlement, located on elevated plateaus of the Western Hill, and the monumental Building 100 in Givati far below?

With this question in mind, it is valuable to consider the assumption contained within the phrase “Jerusalem’s expansion.” This verbiage, which appears commonly in the archaeological literature, presupposes that the large city built on Jerusalem’s two ridge lines during the time of the Judahite kings spread organically from the ancient core on the Southeastern Hill to the Western Hill opposite. This indeed may have taken place. However, other possibilities for the city’s formation exist.

For instance, Nahman Avigad believed that the Western Hill was founded as a kind of isolated daughter city that was later connected to the original city of Jerusalem by a fortification wall. If this kind of process took place, then we are mistaken to speak of an “expansion,” or to anticipate one archaeologically. The evidence from Building 100 would, then, simply reflect local construction irrelevant to the question of when or why the Western Hill was settled. Part of resolving this issue requires examining our presuppositions about how the settlements on each ridge were related to one another. Ultimately, more Iron Age material from the Western Hill is needed.

The data uncovered in this study contributes significantly to the chronology of Iron Age Jerusalem. We will wait eagerly for replies in the scholarly literature, which I assume will appear in short order (an informal one already has).

Jerusalem visualized

Michael Avi-Yonah’s well-known model of Jerusalem was originally displayed at the Holyland Hotel in West Jerusalem. It was later relocated to the Israel Museum, where many visitors view it today. The model shows the city on the eve of its destruction by the Roman army in 70 CE, largely based on information from the writings of Josephus and archaeological data that was known during the 1960s. Avi-Yonah made some updates to the model until 1974 when he passed away, but it seems that not much (if anything) has changed since then (Avi-Yonah and Tsafrir 1992:6). As such, the model reflects some older interpretations, which could be seen as a detraction. However, I find it to be of great value as a reminder that engaging with Jerusalem’s history is an exercise that is inherently limited and subjective, even if the physicality of a model suggests otherwise. Avi-Yonah’s reconstruction, therefore, provides not only a historical interpretation of Jerusalem during the first century CE but also a window into the mind of scholarship during the 1960s.

The angle of this photograph looks east from the area of today’s Jaffa Gate and is framed to highlight the three towers built to the north of Herod the Great’s palace complex. Josephus describes them with detail in book five of The Jewish War. They were named (in order of largest to smallest) after his brother (Phasael), his friend (Hippicus), and his favorite(?) wife (Mariamne). The towers both protect Herod’s palace and guard the vulnerable northern side of Jerusalem. Phasael may have also provided line of sight to Herodium, the closest of Herod’s fortresses which were built along the eastern edge of the Roman Empire.

Mariamne, the smallest and most ornate of the three, can be seen on the far right. Hippicus stands in the center of the photo, with two walls projecting from its base. This tower was built into the line of the “First Wall” or the “Old Wall,” as Josephus calls it. This fortification descends eastward toward the Herodian Temple Mount platform in the distance. Josephus’s “Third Wall,” which was completed on the eve of the revolt projects to the north and runs off the left of the photo. In the center-right stands Phasael, the largest of the three towers. Avi-Yonah identified the ancient courses in the Tower of David, located in the Citadel near Jaffa Gate, as Phasael. I have written a more detailed argument elsewhere that the Tower of David should instead be identified as Hippicus.

As far as I can tell, Avi-Yonah seems to have pioneered a triangular arrangement of Herod’s towers, with Mariamne set back from both Hippicus and Phasael. This represents one possible interpretation of their relationship to each other. Some of his contemporaries also seem to have held the triangular view (Yadin in Yadin (ed) 1976:90), and I have seen it presented in some recent books and articles. However, most scholars prefer to arrange the towers in the line of the “First Wall” one after another. The order and exact placement of each tower is quite diverse in the literature, as there is some archaeological and topographical wiggle room, and Josephus unfortunately never clarifies their exact placement in detail. I presented a paper on the topic at the SBL annual meeting a few years ago and may attempt to publish a view if time allows.

Upcoming (digital) Events

16 May 11:00 AM ET/17:00 JT- Lecture by Elisabetta Boaretto: “Radiocarbon Chronology in Historical Jerusalem and the Challenges to Reconstruct Its Urban Development.” Hosted by the Albright Institute in person and live on Zoom

10 June 11:00 AM ET/17:00 JT- Book launch panel discussing Jodi Magness’s new book Jerusalem Through the Ages. Hosted by the Albright Institute in person and live on Zoom.

Paid Supporters

The next livestream will take place on June 25 from 8:00-9:30pm ET. During these events, we discuss excavations, publications, pop media articles, and developments relevant to historical Jerusalem. I occasionally also present original research. Participants will have opportunities to ask questions. Paid subscribers get access these ongoing events, as well as the archive of recorded livestreams.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee. Less than 1% of readers do this, and it makes an enormous difference.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View the newsletter archive and follow Approaching Jerusalem on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.

a