What Was the Tower of David's Ancient Name?

The Tower of David was one of three towers built north of Herod the Great's palace and described in detail by Josephus. This article explores its setting and identification.

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

Readers of this newsletter will likely be familiar with a large ancient structure known as the Tower of David that sits inside Jaffa Gate near Christ Church and the entrance to the souk on David Street. The Tower of David as we see it today has been subsumed into the Citadel (al-Qal’a) which took its present form during the Mamluk Period—or perhaps earlier—but the tower itself was originally built for a different purpose. While the golden hue of its limestone blocks suggests a relationship with the medieval walls and towers to which it is connected, the masonry style of the Tower of David clearly situates it in an earlier era. The large stone blocks that make up the tower, with their chiseled edges, resemble masonry of the Roman Period, such as the Herodian Temple Mount retaining walls or the Tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron. The tower’s name, connected with King David of renown, is one of several biblical memories that mistakenly became implanted on the Western Hill beginning in the Byzantine Period. Our tower of interest had nothing to do with David!

In a well-known passage from Josephus’s account of the Great Revolt, the first-century Jewish historian pauses his narrative as the Roman army begins their assault on Jerusalem in order to provide his readers with a detailed description of the city’s fortifications and other urban features. This important section includes some of the only written information from the ancient world about Herod the Great’s palace in Jerusalem. In it, Josephus describes three large towers that stood in the city’s northern fortification line which itself ran just north of the palace.

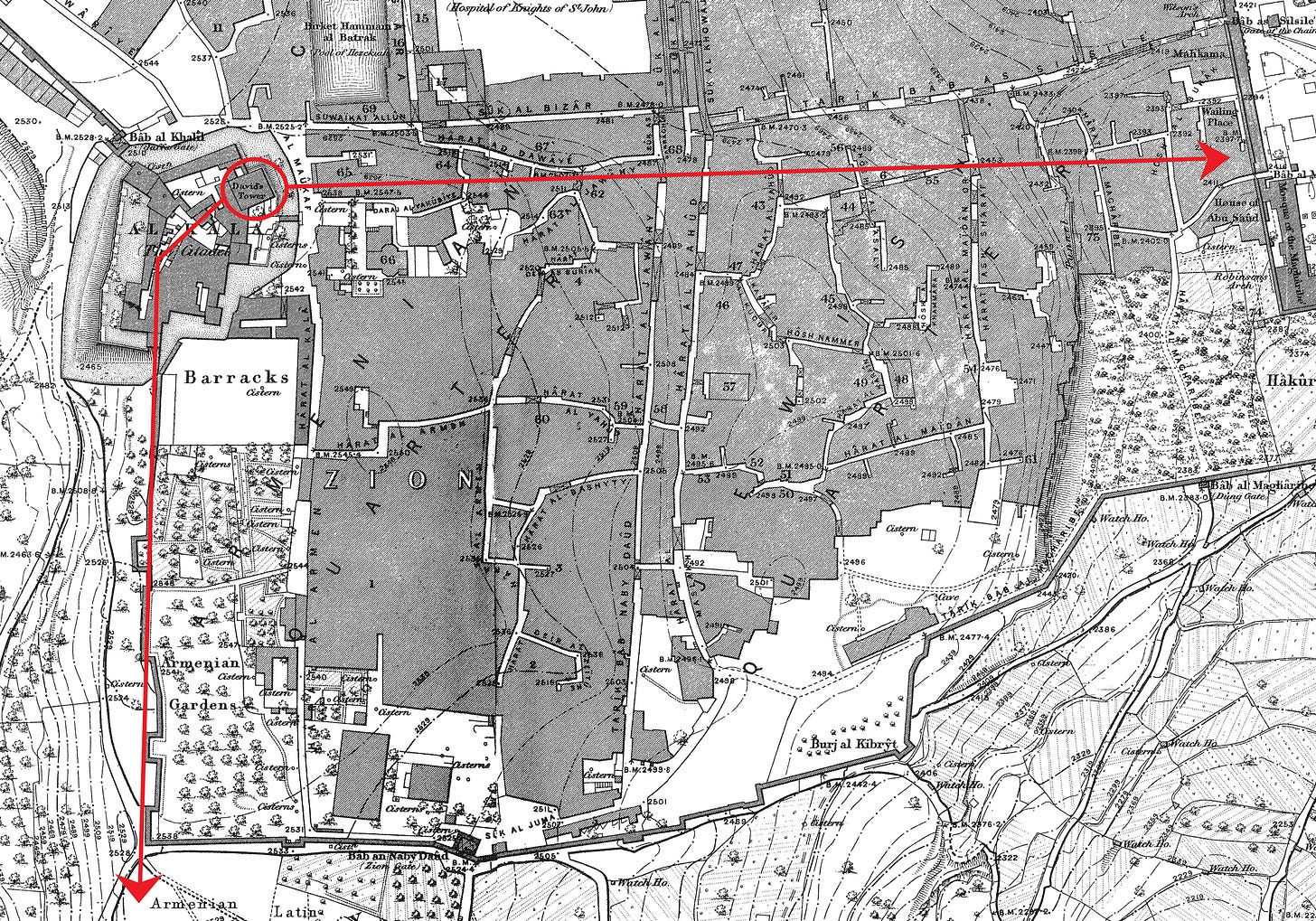

His description also includes important geographical information setting the towers in their relative location. I have written elsewhere about a natural weak point in the northwest corner of the Temple Mount which I termed the “Fortress Saddle.” The Tower of David (and perhaps the other two towers) sat on a saddle of its own that ran northward and must have also carried the line of the so-called Third Wall that protected the northernmost quarters of Jerusalem during the Great Revolt. The Tower of David, therefore, sits in a very strategic location on the precipice of the Transversal Valley which runs east-west from Jaffa Gate to the Noble Sanctuary and the Hinnom Valley (Wadi er-Rababeh) that runs north-south against Jerusalem’s Western Hill. This position magnified the height of the Tower of David, along with the other two of Herod’s towers, and increased their defensive potential.

Josephus provides the names of these towers which commemorated people who were near to Herod’s heart: his brother Phasael, his friend Hippicus, and his wife Mariamne—who Herod later had murdered in jealous rage. According to Josephus, Phasael was the largest of the three towers with a 40x40 cubit base. It stood 90 cubits high. Josephus compares the Phasael tower with Pharos, the famous lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. The base of the Hippicus tower was 25x25 cubits, and its height was 80 cubits. The Mariamne tower stood only 50 cubits high with a 20x20 cubit base, and it was the most ornate of the three.

Our question in this short article is to explore which of these three towers is the best candidate to identify with the Tower of David. No scholars that I am aware of have attempted to identify the Tower of David with the smaller and more ornate Mariamne tower. That leaves only two viable options: Phasael or Hippicus. During most of the 19th century, scholars were split between these two identifications, but the more predominant seems to have been Hippicus. That changed when the German explorer and architect Conrad Schick was allowed access to the Ottoman Citadel in 1878. He examined the Tower of David and claimed its measurements were closer to Phasael than to Hippicus. Schick’s publication of his conclusions had a strong influence on historians and scholars of Jerusalem. James Hanauer, who produced a widely read English guidebook on Jerusalem in 1910 wrote, “Though the tower…is popularly called Hippicus by local guides, it corresponds in its general plan-measurements with the description given by Josephus of the Phasaelus” (1910:6).”

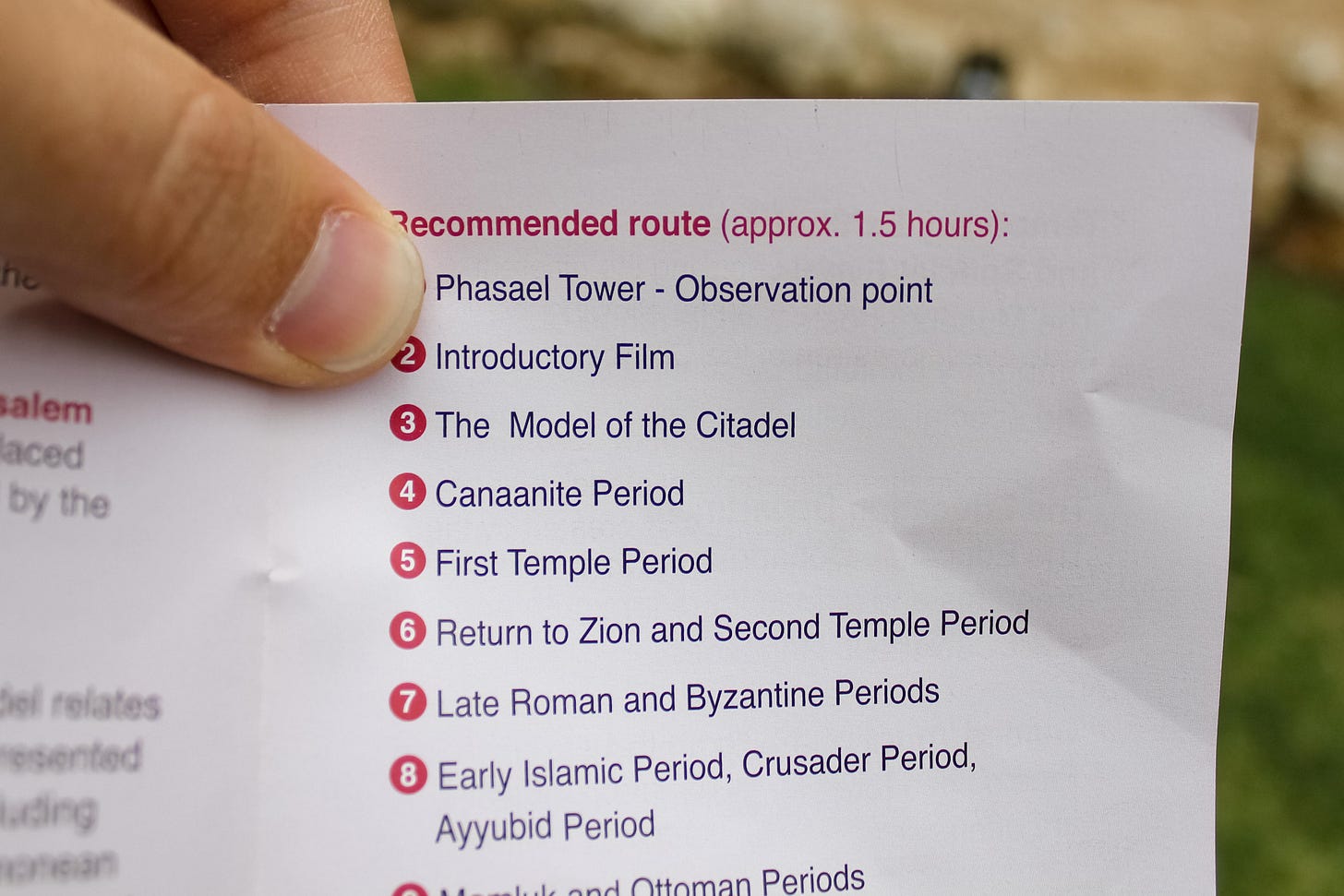

It may be no surprise that the first major excavation in the Citadel took place during the British Mandate Period. The British had a fascination with the Citadel, beginning to clear the area and prepare the adjacent ramparts walk for public consumption quite soon after Jerusalem was placed under military occupation. They later featured the Citadel on stamps and the Palestine Pound.1 The archaeologist Cedric Norman Johns began systematically digging in the Citadel in 1935. He exposed and measured the foundations of the Tower of David at bedrock for the first time. On the basis of his measurements, he boldly claimed that he had proved its equation with the ancient tower Phasael "beyond question" (1940:39). His interpretation was accepted by the majority of scholars in the 20th century, including Kathleen Kenyon, Benjamin Mazar, and Ehud Netzer, along with critical editions of The Jewish War. It is also reflected on material of the Tower of David Museum. While still the dominant view today, some scholars have begun to speak more cautiously, advancing both Hippicus and Phasael as possible options.2

What should we make of the equation between the Tower of David and Herod’s ancient tower Phasael? On closer inspection, there are some problems with the idea, the first being that it assumes Josephus’ measurements of the towers should be taken at face value. But as some scholars have pointed out, a detailed reading of this passage significantly complicates the picture. For example, Josephus writes that all three towers had square bases, but as Johns himself discovered, the base of the Tower of David is, in fact, a rectangle. The measurements given by Hillel Geva are 22.6 m. long by 18.3 m. wide (1981:57). This weakens our confidence in the precision of Josephus’ numbers.

He also grossly exaggerates the size of each limestone block in the towers: “The largeness also of the stones was wonderful…each stone was twenty cubits in length, and ten in breadth, and five in depth” (War V.172). If we take him at face value, the stones that make up the Tower of David should be far more massive in size and far less in number than what are actually preserved. Additionally, Johns’ own excavations showed that several courses of the Tower of David were already buried by the time that Josephus put pen to paper, so there was no way he could know how large the base of the tower actually was.

All this suggests that Josephus intended to speak in general and approximate terms about the size of the three towers, and the best reading of his description would not aim to take them at face value. Hillel Geva, one of the few scholars who has written about the ancient identification of the Tower of David, concludes:

“…the main evidence that we can derive from Josephus' description is the relationship in dimensions between the three towers; that is to say, Phasael was the largest of the three towers, Hippicus smaller and Mariamne the smallest.” (1981:60)

Because every scholar who identifies the Tower of David with Phasael does so solely based on the proximity of its dimensions to those given by Josephus, this identification does not rely on sound evidence. It seems best to seek a different entrypoint to determining the tower’s ancient name.

Beginning already in 1838, the great American scholar Edward Robinson deduced that the Tower of David should be identified with Hippicus based on its geographical position (1846:417). Although it became a minority view during the 20th century, this idea was revived by a handful of scholars during the 20th century, including John Simons, Hillel Geva (mentioned above), Dan Bahat, and Leen Ritmeyer. Rather than relying only on the accuracy of Josephus’ numbers in one passage, this view attempts to make the best sense of all of Josephus’ descriptions of the towers, as well as the topography near the towers.

These scholars have noted that Josephus’ descriptions of the tower Hippicus require that it stand on the northwestern corner of the so-called First Wall. This fortification wall surrounded Jerusalem’s Western Hill and in all likelihood followed the trajectory of the earlier Iron Age wall that was built six centuries earlier during the Judahite Kingdom. In his well-known and detailed description of this line of fortification, Josephus uses Hippicus as a starting point from which he describes the line of wall first running east toward the Temple Mount and then, starting with Hippicus again, running south. His general description of the wall corresponds well with both Jerusalem’s geography and what is known archaeologically about this ancient line of fortification. Josephus later tells us that Hippicus was the starting point of the so-called Third Wall from which it ran north (as mentioned above). Here is the relevant part of the description:

“Now that wall began on the north, at the tower called "Hippicus," and extended as far as the "Xistus," a place so called, and then, joining to the council-house, ended at the west cloister of the temple. But if we go the other way westward, it began at the same place, and extended through a place called "Bethso," to the gate of the Essenes” (War V.142)

As other proponents of this view have noted, the strategic location of Hippicus at the northwestern corner of the city probably accounts for why this tower is mentioned throughout The Jewish War more than any other. For instance, the Roman General Titus is said to begin his assault on the city walls with part of his troops near the tower:

“…as for Titus himself, he was but about two furlongs distant from the wall, at that part of it where was the corner and over against that tower which was called Psephinus, at which tower the compass of the wall belonging to the north bended, and extended itself over against the west; but the other part of the army fortified itself at the tower called Hippicus...” (V.133-135)

This passage suggests that both the towers Psephinus and Hippicus stood in the western line of fortifications where they would naturally be encountered by the Roman army during their approach. It is interesting that although the tower Phasael was the highest of the three according to Josephus’ measurements, it is not mentioned at all here. This suggests it was built further to the east and was not intended to fortify the western side of Jerusalem in the same way Hippicus was.

As I have already mentioned, only by locating Hippicus on the northwest corner of the First Wall can we accommodate all this data. Excavations of Johns and other archeologists in this area have revealed only one ancient line of wall in which the towers could be set (see photo above). This line bends through the Citadel and then turns south along the scarp of the Hinnom Valley. There is no other archaeological candidate for an ancient tower from the first century anywhere along this wall or anywhere west or north of the Tower of David. Therefore, the identification of the Tower of David with Phasael is very unlikely, since it would require the Hippicus Tower to be built either east or north of it. Either configuration would contradict the overall picture of the data that we have from Josephus which situates Hippicus in the northwestern corner of the city wall. Taken together, this suggests that the best candidate for the Tower of David is Hippicus rather than Phasael.

Although Josephus described three towers set in Jerusalem’s northern fortification line to the north of Herod’s palace, only the Tower of David remains standing today, and the other two have disappeared. A discussion of where they were located, how the three towers were arranged in relationship to each other, and the nature of their collective function is another set of issues that deserves its own consideration in the future.

Yair Wallach notes that these items showed only the bare walls and towers of the citadel and omitted the shops and cafes below. This framing ignored Jerusalem’s living elements in order to front the city’s antiquity (2020:128). Ironically the oldest monument in the Citadel, the Tower of David, was not depicted. A similar angle of the western portion of the Citadel is used as the logo for the Tower of David Museum today.

For example, in The Sacred Bridge, Steven Notley writes simply that "The lower portions of one of Herod's towers can still be seen today at the Citadel near Jaffa Gate" (2014:346). Orit Peleg-Barkat likewise mentions that the Tower of David is "alternatively recognized by scholars as either Hippicus or Phasael" (2019:55).

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous editions of this newsletter or follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.