Jerusalem in Brief (No. 13)

Jerusalem on the Madaba Map and a new book about Christian pilgrimage in the pre-Crusader city

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription and receive unique Jerusalem-related benefits.

Jerusalem Visualized

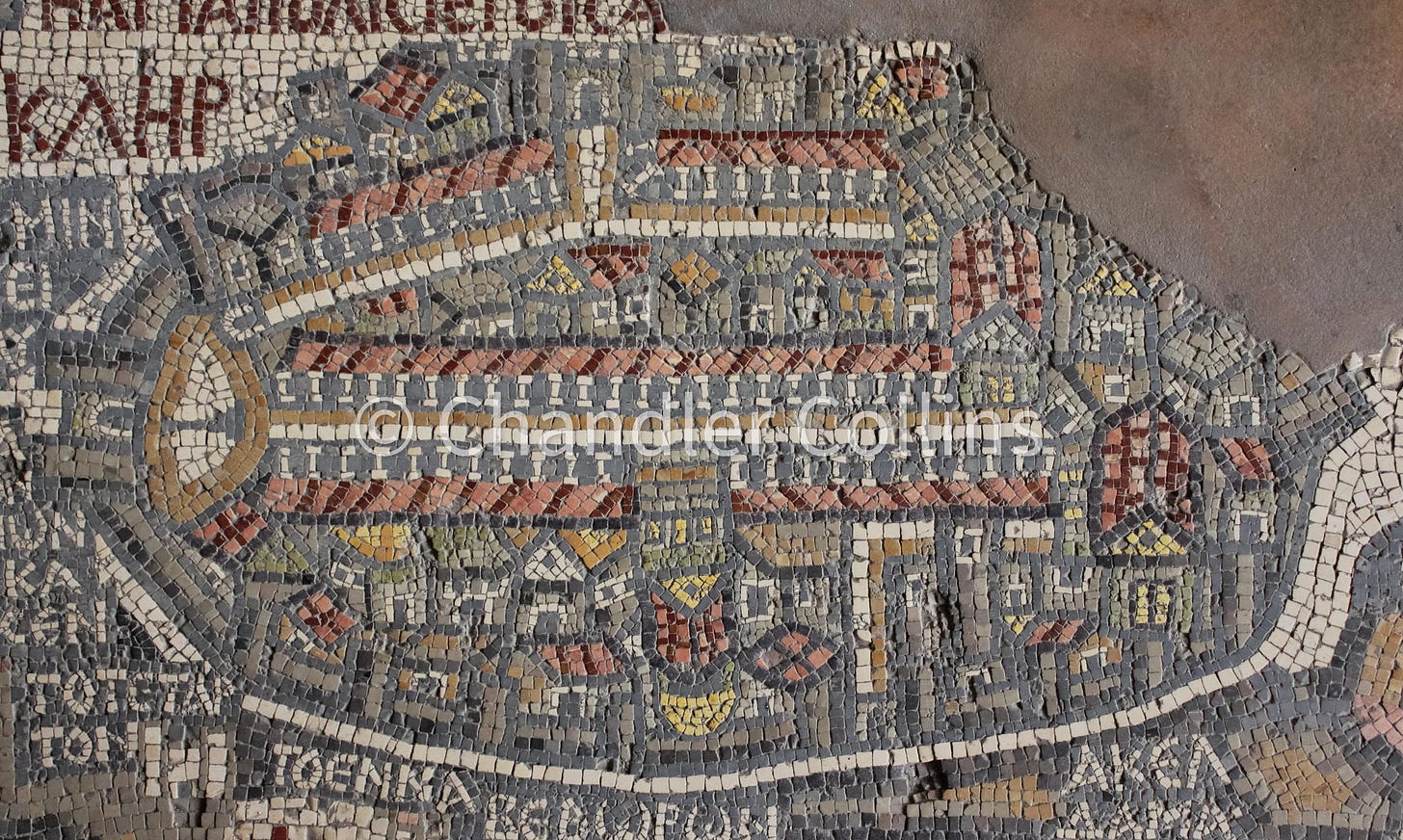

The photo above shows a mosaic depiction of Jerusalem on the Madaba Map. This mosaic map was found in 1884 among the ruins of a Byzantine Church in Madaba, Jordan during the construction of a new church there (Donner 1992:11). It is generally thought to date to the mid-late 6th century CE and originally illustrated the entire Eastern Mediterranean. The Madaba Map is a treasure of late antiquity, depicting cities, holy sites, geographical features, flora and fauna, and aspects related to travel. It also provides a window into biblical interpretation during the Byzantine Period. Some sections were destroyed over the centuries and, unfortunately, subsequent to the discovery as well (Donner 1992:15). Thankfully, the portion which shows Jerusalem is almost entirely intact, with only minimal damage to the southeast corner of the city. In this post, we will take a look at some major features of Jerusalem that appear on the Madaba Map.

The city is pictured in the center of the mosaic and was made extraordinarily large, more so than any other, to indicate its theological importance. Jerusalem (and the entire map) is oriented toward the east, as was sometimes the case prior to the popularization of the compass. It is often observed that the artist(s) chose to depict the city from a bird’s eye view but faced the difficulty of how to illustrate its interior buildings. The angle they selected may be compared to the view above a freshly scoured loaf of sourdough bread just prior to going in the oven. Imagine the cut of the dough running along the main north-south street in the center (known as the Cardo Maximus), with its sides falling open in lateral directions to the east and west. The roofs of buildings above the Cardo and its eastern colonnades all point upward (eastward). The lower (western) colonnade points in the opposite direction, but the buildings below the Cardo are not consistently oriented, with some facing down and others facing up.

As many have observed, the artist probably chose to adopt this framing due to the orientation of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (Resurrection), which is shown prominently in the center of the map. The entrance to the church was accessed by a monumental staircase coming directly off of the Cardo. The golden dome of this building, shown on the map below its red-roofed basilica, sat over the traditional Tomb of Christ. This urban plan resulted in a church building that was unusually oriented toward the west, rather than the typical east.

An oval-shaped wall surrounds the city with gates and towers. Two large gates with flanking towers can been seen at the top center and just right of center at the bottom. These were probably built near Lions’ Gate and Jaffa Gate of today’s Old City wall respectively. The largest gate on the Jerusalem mosaic is located at the far left (north), on the site of today’s Damascus Gate. It also features two flanking towers which are shown on the map. Their remains can be seen in the exposed area in front of the Ottoman Period gate when visiting today, which were also used as a foundation for its construction.

Inside the northern gate is a white oval plaza with a black pillar, usually thought to have originally held a statue of Emperor Hadrian (Magness 2024:302-303, 347). The modern Arabic name of Damascus Gate (Bab al-’Amud = “The Gate of the Pillar”) is widely regarded as preserving this historical reality (Arnon 1992:61n17).

Several streets can be seen on the map, including the Cardo Maximus which runs from the oval plaza in the north to another large basilica on the southeast known as the Nea Church (more info here). The Cardo Maximus is the largest visible street in the mosaic, and several sections of it have been recovered archaeologically. The most publicly accessible parts are displayed in the modern Jewish Quarter (more info here). Salvage excavations at various places in the Old City have also uncovered small pieces of the Cardo, including one that was recently published. A secondary Cardo (the “Eastern Cardo”) is shown at the top of the map running in an angled direction southeast from the oval plaza and then straight south. Sections of this street have also been uncovered in excavations (more info here).

One other interesting observation (among many that could be mentioned) is that the map shows a large rectangular freestanding tower just inside the western gate (red X on photo below). It also seems that another shorter tower is depicted standing next to it on the left (blue X on the same photo). If this is the case, it indicates that two of the three towers built north of Herod’s palace (mentioned in the writings of Josephus) were still standing during this time (see more here). It is also possible that all three stood but that the artist did not have adequate room to illustrate them. One of the towers shown on the map, likely the taller of the two, must be the one known today as Tower of David, and it seems to have already gained that name by the time the map was originally created (Donner 1992:93). In another post, I argued that the Tower of David should almost certainly be identified with the ancient tower of Hippicus built during the days of Herod. The other tower shown on the map (perhaps Mariamne) fell sometime after.

Jerusalem’s depiction on the Madaba Map attests to a familiarity with the built environment of the city during the 6th century CE. However, it is also a theological creation. The landscape is full of disproportionately large churches, so that much of Jerusalem’s terrain is covered by them. It is also conspicuous that the Herodian Temple Mount is not pictured, though it has been suggested that a single line of dark stones may allude to the presence of its ruins (Avi-Yonah 1954:59; Donner 1992:94). The complete (or near-complete) omission of this ca. 35-acre monument and prominent positioning of the Holy Sepulcher seems to have been a deliberate anti-Jewish artistic decision, meant to demonstrate the supersession of Christianity. It is interesting that the artist did not decide instead to show the ruins of the Temple Mount in a more obvious way, as a reminder of Jesus’ prophecy about its pending destruction (Matt. 24:2; Mark 13:2; Lk. 19:44; 21:6). The ruined Temple Mount area would be later rebuilt as the Noble Sanctuary, after the Christian city fell into the hands of the Muslims during the 7th century.

Recent Arrivals

I was intrigued when I discovered Rodney Aist’s new book Walking the Jerusalem Circuit: In the Footsteps of Pilgrims before the Crusades and immediately ordered a copy. Aist serves as the Course Director at Saint George’s College in Jerusalem and has published several other works on Christian pilgrimage. In this book, he aims to provide insight into, and promote participation in, the pilgrimage circuit in Jerusalem that was established near the end of the Byzantine Period and used during the Early Islamic Period until the Crusades. The work is equal parts primary source overview, historical reconstruction, pilgrimage primer, and logistical guidebook.

Aist reconstructs a pre-Crusader pilgrimage route in Jerusalem on the basis of four historical writings which date from the early 7th century-870 CE:

Sophronius

an Armenian guide by an unknown author

Willibald

Bernard the Monk

He provides background information and a short overview for each source (pgs. 11-19). They dovetail nicely with the depiction of Jerusalem on the Madaba Map, which we just discussed (6-7). Aist notes that the pilgrimage circuit fluctuated over time and was never fully standardized, so the specific progression is slightly different in each source. However, they display an overall similarity in their direction of route. Willibald’s recording of his circuit in Jerusalem was made more than 50(!) years after his visit, suggesting that repetition of the itinerary while in Jerusalem ingrained its progression into his memory (5-6, 16).

According to Aist’s evaluation of the sources, the pre-Crusader pilgrimage circuit in Jerusalem began at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and ended on top of the Mount of Olives, overlooking the city after a visit to Eleona or the Church of the Ascension (7-11). From the Sepulcher, pilgrims arrived at the Church of Holy Zion via the southern extension of the Cardo Maximus. They then descended the slopes of modern Mount Zion, accessing the Eastern Cardo near today’s Dung Gate, and walked around the ruins of the Herodian Temple Mount (and later, Noble Sanctuary) in a counterclockwise manner. This facilitated stops at several sites, including the Pool of Bethesda. Pilgrims then exited the city in the area of today’s Lions’ Gate and experienced sites in the Kidron Valley (including Gethsemane) before ascending the Mount of Olives.

Having established the pre-Crusader pilgrimage circuit in Jerusalem, the author invites readers to join in participation. This is not a call to peel away the layers of contemporary Jerusalem in order to engage directly with the New Testament city via archaeological material (35-36). Rather than walking where Jesus walked, Aist envisions walking “in the footsteps of those who walked in the footsteps of Jesus” (1). Neither does the book aim recreate the Byzantine experience and mentally jettison the modern context (1). Such an exercise would not be possible anyway, as he mentions, due to variations in pilgrim accounts and the unknown locations of several stops on the circuit (8-9). Instead, he invites participants to immerse themselves in the circuit’s itinerary while simultaneously engaging Jerusalem’s rich historical layering, diverse living communities, its complications, suffering, and heavenly associations (22-23).

The final three-fourths of the book contains a blow by blow entry for each station on the circuit. This is prefaced by helpful information about safety, food, bathrooms, timing, structure, and other logistical issues (24-34). Aist breaks the circuit down into 16 stations. He offers a checklist of action items to aid in the commemoration of each station. They promote both inward reflection and engagement with the physical space of the station. Each entry also includes background information, as well as relevant excerpts from pre-Crusader sources and, when possible, the New Testament. Aist encourages participants in the circuit to engage creatively with the stations, going off script when and how they feel the urge to do so (xiii). A bibliography of ancient and modern sources for further reading concludes the work.

This little book provides an approachable entry point into Christian pilgrimage in Jerusalem during the Byzantine and Early Islamic Periods. Readers will gain a clear understanding of important ancient sources and see them actualized on the city’s landscape. It will be a valuable addition for Christian pilgrims traveling to Jerusalem and anyone of any background who is interested in its history.

Upcoming Events

Oct 22-23: The annual New Studies in the Archaeology of Jerusalem and Its Surroundings conference in person, in Jerusalem.

29 Oct 17:00 JT - Book launch for Walking the Jerusalem Circuit by Rodney Aist at the Albright Institute. In person only. More info here.

Nov 19-22: The annual meeting of the American Schools of Overseas Research (ASOR) will feature a session on “Jerusalem and the Archaeology of the Sacred City.”

Paid Supporters

The next Approaching Jerusalem livestream for paid supporters will take place on December 9 from 8:00-9:30pm ET).

During these events, I discuss excavations, publications, pop media articles, and developments relevant to historical Jerusalem. I also share resources and occasionally present original research. Participants have the opportunity to ask questions. Paid subscribers also get access to the archive of previous livestreams, which is currently about 17 hours of watch time.

This material was 100% human composed. We do not use AI at any stage of research or writing.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee. Less than 1% of readers do this, and it makes an enormous difference.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View the newsletter archive and follow Approaching Jerusalem on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.

The interpretation of the Madaba map is very original, especially the use of the sourdough bread image to orient the viewer. Its supercessionary intent is intriguing. The review of Aist's book provided a very grounded itinerary and human experience of early Medieval pilgrimage. Thank you.