Appreciating Jerusalem's "Fortress Saddle"

A small bedrock saddle projecting from the Noble Sanctuary served as the location of several strongholds in Jerusalem's history. Here's where you can see it today and why it's important.

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

Finding A Saddle

The many pilgrims and residents who walk along the Via Dolorosa pass over an unobtrusive but significant geographical feature for Jerusalem’s historical development. I did so many times myself before registering that I was actually walking over the crest of a saddle that represented the city’s historical weak point during several different periods (a good reminder to always be aware of what our feet experience as we walk in Jerusalem). This street, which runs between Lions’ Gate and the Austrian Hospice, rises to a plateau near the Ecce Homo Arch and descends from it in both directions. The plateau at the top of the saddle sits near the al-Omariya Elementary School and first two Stations of the Cross. I am not aware that any names have been given to this saddle by scholars (perhaps they have!). I have termed it the “Fortress Saddle” for the sake of an identifier and to hint at its historical function.

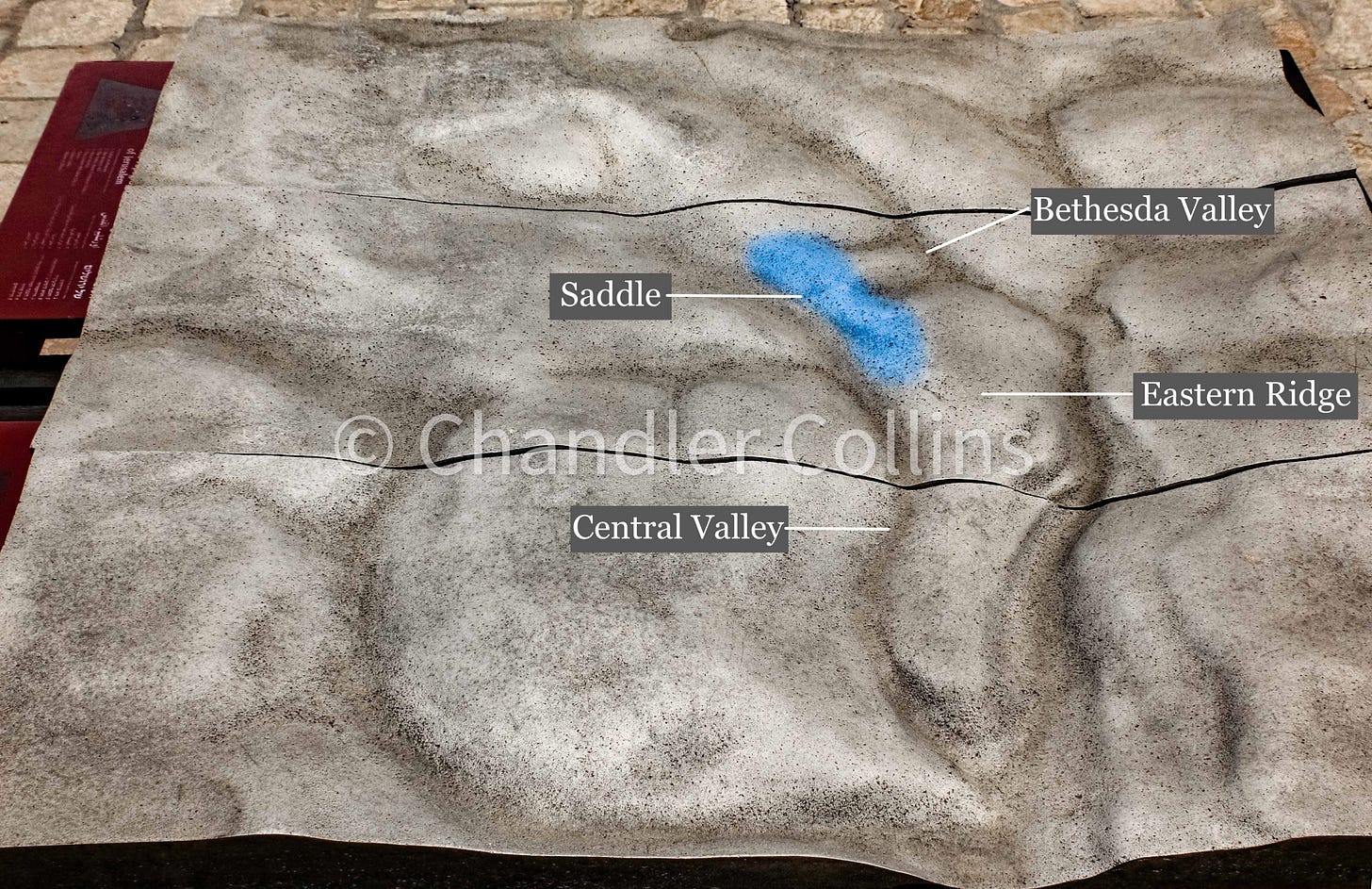

It is important to understand that this elevated saddle divides two wadi (valley) systems. The system on the west side of the saddle is called “the Tyropoeon Valley” by Josephus (John Simons later renamed it “the Central Valley,” a term which is widely used today). This valley runs along al-Wad Street (Ṭariq al-Wad) from the area north of Damascus Gate southward to the bottom of Silwan. The wadi system on the eastern side of the Fortress Saddle is a small tributary of the Kidron Valley (Wadi en-Nar) and is known by several modern names. Dan Bahat calls it the Beth Zetha Valley (2011:11-12). Others call it the Bethesda Valley, St. Anne’s Valley, or something else. Its name is not as important as understanding (1) that this valley existed (it is completely covered today) and (2) how it affected the development of ancient Jerusalem (see below). The next time you find yourself under the Ecce Homo Arch, be sure to look both directions and appreciate how the street drops into each of these wadi systems.

Other Hints

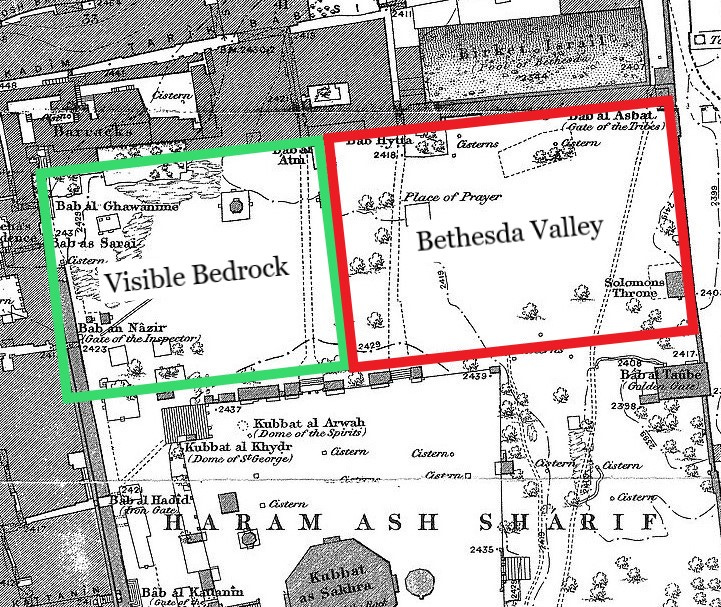

This section of the Via Dolorosa is the place where you can most clearly appreciate the existence of the Fortress Saddle, but additional hints present themselves in the visible bedrock on the Noble Sanctuary. For instance, a well-known sheer face of limestone can be seen in the northwest corner which serves as the foundation for the al-Omariya School mentioned above. The majority of scholars believe the Antonia Fortress was built atop this bedrock in the first century BCE, although their reconstructions of the size and plan of the fortress vary. Lines of bedrock can also be seen near Bab al-Ghawanima, the northwesternmost gate of the Noble Sanctuary. Here the ground also rises in elevation with the saddle.

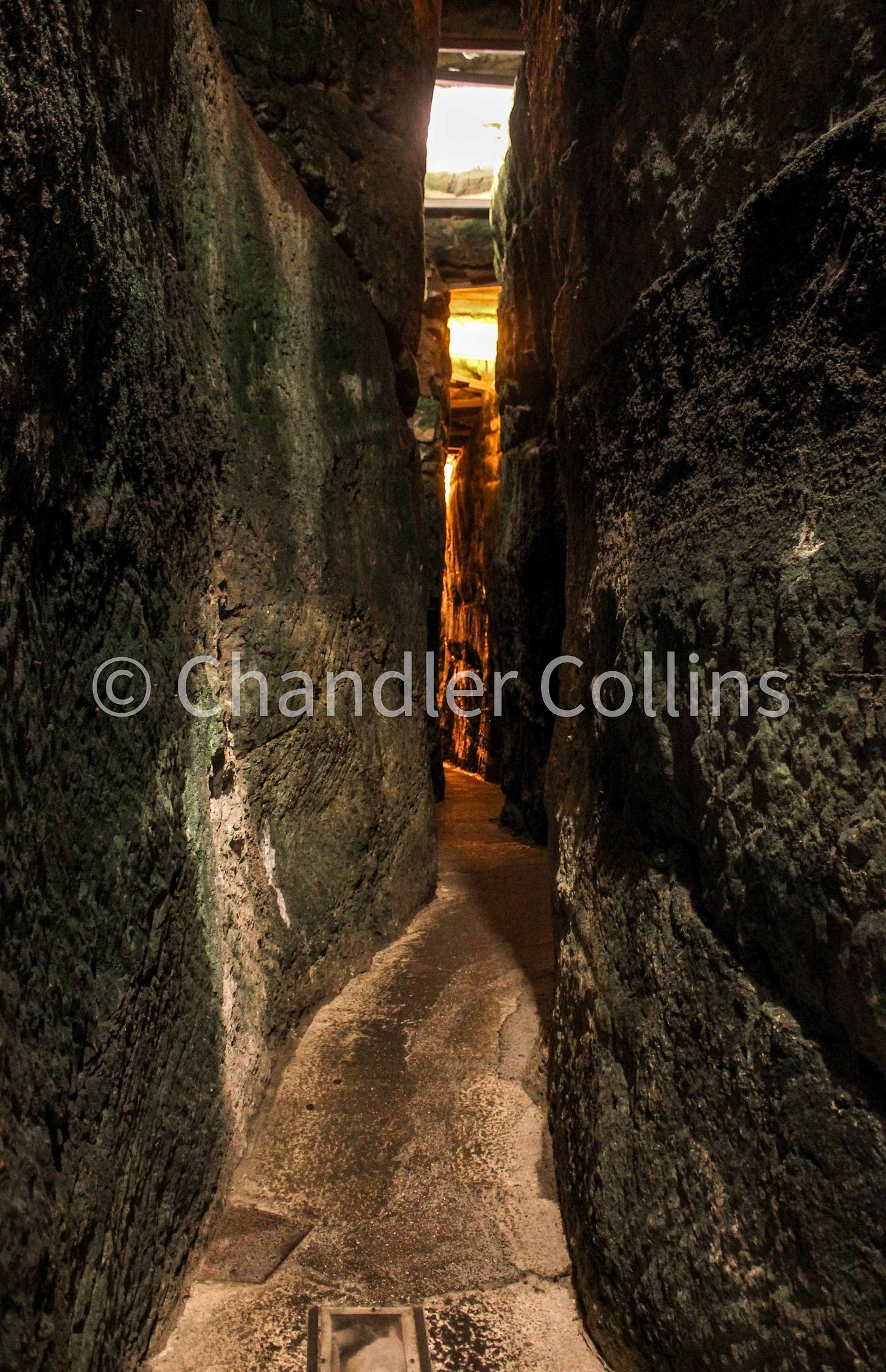

It is also helpful to notice other protrusions of bedrock within the green space to the north of the Dome of the Rock. Observant visitors walking here will find that patches of bedrock only appear in the western part of the garden (about the western third) but will see that they disappear on the eastern side. This illustrates something about the underlying topography. These patches of bedrock are in fact glimpses of the Fortress Saddle which runs through this area and projects northward to the Via Dolorosa. However, the eastern portion of this green space is artificial fill which covered part of the Bethesda Valley when it came to be included in the extension of Herod’s Temple Mount platform. Evidence of this same line of bedrock also appears below ground in the Western Wall Tunnels.1

Historical Importance

Although small, this bedrock saddle was strategically important at several periods of Jerusalem’s history. Scholars regularly emphasize that the geographical weak point of the city was its north side at nearly every phase of its development. Recall that the temple was built at the top of the eastern ridge during the time of the Kingdom of Judah. At this point, its most vulnerable area—and therefore Jerusalem’s most vulnerable area which could not be protected by deep valleys—was along the Fortress Saddle.

As mentioned above, we know that in the late first century BCE the Antonia Fortress was built along this small ridge. Josephus tells us that an earlier fortress called the Baris had been built in this area during the Hellenistic Period.2 The idea that there may have been an even earlier (Iron Age) stronghold—or at least significant fortifications—at this vulnerable point makes good geographical sense. Leen Ritmeyer, for instance, reconstructs the Tower of Hananel (Neh. 2:8; Jer.31:38; Zech. 14:10) here (2005:28-29).3 When Jerusalem was destroyed in 70 CE and the boundaries of the city were extended northward in later periods, the Fortress Saddle—once a meaningful landmark for the city’s growth and defense—lost its strategic importance and was enveloped in the mass of buildings and streets.

Applying the geography of Jerusalem, as best we can understand it, to its historical development, reveals helpful patterns that illuminate our interpretation of the city’s past. Because the topography has changed significantly since antiquity, its study will always involve some degree of creative imagination—or at least learning to internalize what our feet experience as we traverse the city today.

For archaeological evidence relating to the Western Wall Tunnels, see Bahat 2000:187-190.

For a discussion of the Baris, see Wightman 1990-1:7-35.

See a model of Ritmeyer’s reconstruction of the Towers of Hananel and Meah here.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous editions of this newsletter or follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.