Did a Mass of Israelite Refugees Flee to Ancient Jerusalem? The Development of an Idea

Magen Broshi's refugee hypothesis aimed to explain how Iron Age Jerusalem expanded to include the Western Hill. It has been widely accepted and developed, but some scholars question its usefulness.

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

Pick up a recent book or article covering the history of ancient Israel or the formation of the Hebrew Bible, and you will likely encounter the suggestion that a large number of refugees from the kingdom of Israel fled to Jerusalem leading up to and after 722 BCE when the capital city Samaria fell to the Assyrian Empire. Once in Jerusalem, they are thought to have settled on the Western Hill and vastly increased the city’s population. This idea is widely discussed in research, and scholars have adopted it with some variety. Today’s newsletter explores how this situation came to be, along with some challenges to the idea.

The Genesis of the Refugee Hypothesis

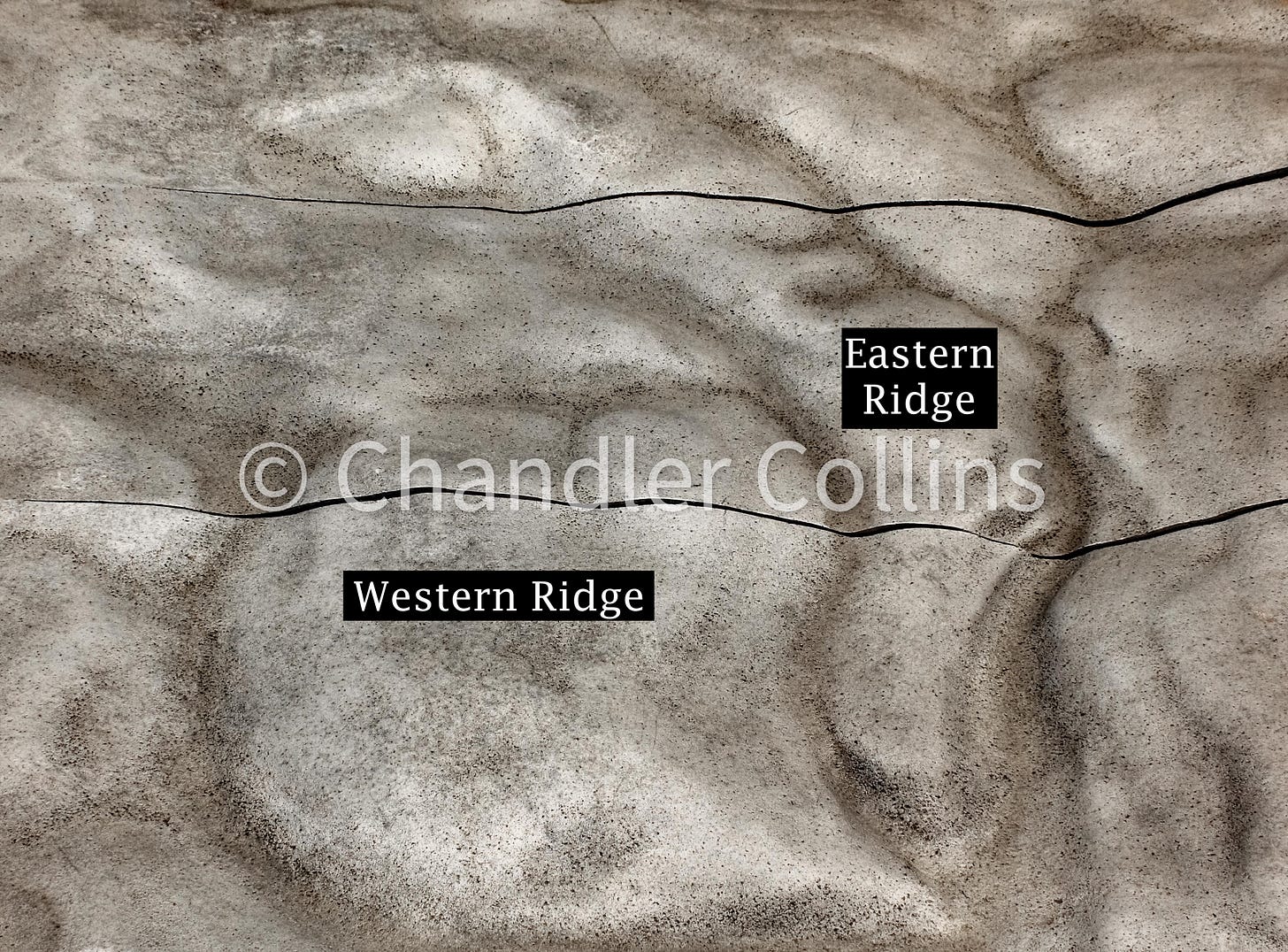

To understand how the idea of Israelite refugees in Jerusalem has become so popular, we need backtrack to the 1960s and the following decades, when several large-scale excavations first took place on Jerusalem’s Western Hill. Leading up to these excavations, scholars disagreed with each other about the size of Jerusalem during what archaeologists call the Iron Age II Period (the time of the so-called United Monarchy and later Judahite Monarchy from roughly David to Zedekiah). The vast majority of scholars believed that Iron Age Jerusalem had never extended beyond the city’s eastern ridge in any significant way. A small minority argued that the settlement of the city, and likely its walls, had indeed extended to the higher Western Hill (today including Mount Zion and the modern Armenian and Jewish Quarters).

Scholars who discussed this issue before the 1960s had to rely solely on the Bible and other ancient literature, the geography of Jerusalem, and some small remains from earlier digs on the Western Hill. New and major excavations, beginning with Kathleen Kenyon in 1961, provided fresh evidence to evaluate the issue. These digs surprisingly revealed that the Western Hill had indeed been settled during a portion of the Judahite Monarchy. Material remains from the 8th-6th centuries BCE were found in nearly all areas that were excavated, showing that ancient Jerusalem had grown to an area much larger than had been previously thought.

The most impressive of these remains was a fortification wall uncovered by Nachman Avigad and dated by him to the reign of King Hezekiah. Many readers of this newsletter will have seen remains of it that are preserved in an open-air museum in the Jewish Quarter as it was reconstructed after 1967. Based on the totality of remains that were uncovered, most scholars came to accept that the entire Western Hill had been surrounded by an extension of this same fortification wall. The question quickly turned to how this growth could be explained.

In 1974, Israeli archaeologist Magen Broshi (who himself excavated extensively on the Western Hill)1 published an article where he estimated that Jerusalem had ballooned to three or four times its size during the reigns of Hezekiah and Manasseh. He argued that this could not be accounted for through the gradual growth of the city alone and suggested that this population explosion could be explained by two waves of refugees who settled in the city. The first wave was of Israelites fleeing the Assyrian destruction of Samaria in 722 BCE, and that was followed by another wave of Judahites from the Shephelah (lowlands) fleeing Sennacherib in 701 BCE. Broshi’s ingenious idea introduced the refugee hypothesis into scholarship for the first time and gave explanatory power to the new archaeological finds. Many scholars accepted and popularized it in articles and books in the 1970s and decades following.

Shifts and Adaptions

In recent decades, Broshi’s nameless mass of refugees have taken on more tangible roles and identities within biblical studies and archaeology. One popular stream of thought understands the displaced Israelites as the conduit by which northern traditions came to be included in the Bible. J. Maxwell Miller and John Hayes are one of many examples of scholars who mention this possibility:

"Some of the northern population may have fled south to avoid deportation. Many northern traditions may have been brought south also, eventually to find their way into the Hebrew Scriptures. Among such traditions may have been some form of the royal annals, an early form of Deuteronomy, and prophetical narratives such as the Elijah and Elisha stories." (2006:390)

Among scholars who take this point of view, some believe that parts of the northern material brought by the refugees were adopted into the biblical books (perhaps in an early form of the book of Kings) very quickly. This would have been a kind of concession to the refugees by Hezekiah who wanted to incorporate them into the Judahite Kingdom. Others agree that refugees brought these northern traditions to Jerusalem but see the process by which they came to be included in the Bible as more complex.

Sometimes archaeologists will invoke the refugee hypothesis as a way to explain Israelite material that is found in Jerusalem. One example is a bulla that was unearthed in an Iron Age building (Area U) that sits above Jerusalem’s perennial spring. The bulla contains the personal name “Maʾasyahu (son of) ʾElyaqim.” The name Maʾasyahu, understood to mean “YHWH has rejected,” is a strange name for any parent to give their child. The scholars who published the bulla wonder if ‘Elyaqim may have been a northern refugee whose son’s name was inspired by the fall of Israel’s kingdom (Mendel-Geberovich et al 2020:165). Another bulla found nearby contains a surprising combination of personal names for a Jersualemite: “Aḫab son of Menaḫem.” Since both were names of Israelite kings, the excavators suggest that this person may also have been an Israelite refugee. A few other archaeological remains in Jerusalem have been connected with Israelite refugees as well.

Scholars who accept the idea that Israelite refugees fled to Jerusalem have developed different points of view about their historical background and social status. For instance, William Schniedewind assumes that a significant number of the refugees who fled to Jerusalem were literate elites (2004:95), some of whom may have even been responsible for carving the Siloam Tunnel Inscription (2010:198-199 with Gary Rendsburg). On the other hand, Israel Finkelstein seems to believe the refugees came largely from rural settings and lacked the skills to rise to the upper echelon of Judahite society (2008:509). Obviously, the historical background one assigns to the refugees will inform our understanding of how they were incorporated into the kingdom of Judah and also how we might be able to identify them in the archaeological record.

This brief review shows that since Broshi introduced the refugee hypothesis, it has been adapted by scholars in a variety of ways which are not always consistent with each other. It is also interesting that although Broshi’s theory was created to explain Jerusalem’s growth onto the Western Hill, scholars have applied it to finds in other parts of the city, such as on the Southwestern Hill. It has also been used to explain more theoretical issues, such as how northern material came to be included in the Bible.

Complicating the Consensus

Although the theory that Israelite refugees fled in mass to Jerusalem and settled on the Western Hill has become a popular one, a growing minority(?) of scholars have pointed out problems with it. The most basic is that such an event is not documented in the Bible or any other ancient text. Of course, many important historical events, people, and cities are not mentioned in the Bible for a variety of reasons, but it seems reasonable to expect some reference to these refugees if they altered the shape and life of Jerusalem itself so quickly and dramatically. Another important issue is the ability of Judah and Jerusalem to integrate the mass of refugees without being overwhelmed by them (Guillaume 2008). Nadav Na’aman, perhaps the fiercest opponent to the refugee hypothesis, has proposed an alternative explanation of the archaeological evidence in several articles. He argues that the Western Hill began to be occupied in the early 8th or even late 9th century BCE, well before Israelites would have fled Assyrian attacks (2007; 2009; 2014).

An understanding of this issue is also dependent on the population estimates that a given scholar uses for Iron Age Jerusalem. Some researchers assume that Jerusalem grew only two times its size. Others say it grew as high as ten times. Obviously, each of these assumptions will lead to very different historical reconstructions in order to account for Jerusalem’s growth. Population estimates can quickly give way to wild guesses when we experience gaps in the data, such as trying to calculate the ancient population density of the Western Hill. One interpretation of the archaeological data from this hill understands that it was packed with inhabitants, turning Jerusalem into a true metropolis. On the other hand, the fortification wall around the Western Hill may have simply followed the most defensible line, whether the areas inside were densely occupied or not. If this was the case, even though the size of the walled city greatly increased, Jerusalem’s inhabitants did not necessarily occupy all areas of it. This view would relieve the pressure to explain a supposed population explosion.

Taking a wider view at the development of the refugee hypothesis also allows us to see that Broshi formulated the idea as the first major digs on the Western Hill were still ongoing and unpublished. From its inception, then, the refugee hypothesis has been based on a very preliminary understanding of the archaeological material from the Western Hill. In a manner similar to first-to-market products, the refugee hypothesis has enjoyed the advantage of being the original explanation of Iron Age material on the Western Hill and has been repeated in scholarly literature for almost 50 years. However, major digs from the 1970s-1980s that have a direct bearing on how to interpret this issue are still being published, and the traditional understanding is now being tapered by other excavations that suggest Jerusalem experienced slower growth over time (e.g. Uziel and Szanton 2015:248).

This is an active research topic for me, but I tend to see the refugee hypothesis as the application of a single cause to what was probably a longer and more complicated settlement process. Many factors could have led to Jerusalem’s expansion onto the Western Hill: gradual growth, agricultural development, immigration to Judah’s capital, the settling down of nomads, or some combination of these and other factors. Perhaps some refugees did arrive from the Kingdom of Israel or from the Shephelah after Sennacherib’s campaign in 701 BCE, but I’m not sure we should assume they could have settled only on the Western Hill rather than in other parts of Jerusalem or its hinterland. It is also possible to interpret northern material unearthed in Jerusalem in a variety of ways. Israelite names on an artifact need not necessarily imply that an artifact was brought or produced by a refugee. It might have arrived by other processes (trade) or could simply be a reflection of the interaction between Israelites and Judahites who shared aspects of culture and geography.

These problems likely cannot be solved by the current archaeological data, so scholars continue to debate the topic. The issue certainly deserves a much longer exploration than there is space for here. In the meantime, the point of departure in my own research is to unmoor the refugee hypothesis from its pride of place and explore other historical possibilities that might explain why and how Jerusalem’s Western Hill became populated in the Iron Age.

These excavations, which took place along the western and southern Old City walls, in the Armenian Garden in the southwestern corner of the Old City, in the Armenian Convent on Mount Zion, and at Christ Church are not yet published. However, Shimon Gibson has mentioned that he is in the process of publishing them.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous editions of this newsletter or follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.

Imho, Isaiah 11 pictures the Gentile refugees living on the western hill, describing them as various dangerous animals **who weren't hurting anyone**, living right on God's "holy mountain" - Mount Zion. Josephus agrees that Mount Zion was on the western hill (Wars of the Jews Book V chapter 4). These would also have included Israelite refugees, of course, but the Gentile refugees would've been from the smaller nation-states surrounding Israel and Judah, which previously were their enemies.

Israel and Judah couldn't achieve lasting peace through military means, but God was able to create peace HIS way...a lesson that I think we should learn from today.