Putting the "Robinson" back in "Robinson's Arch"

The pioneering American explorer's interpretation of Josephus was widely accepted before being disproved. Let's relive the genesis of "Robinson's Arch" and explore the popularity of Robinson's theory.

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

In 1838 the American scholar Edward Robinson made an important visit to Ottoman Palestine with Eli Smith, Robinson’s former student and a talented Arabist. Their journey, which has been written about extensively, was prompted by a desire to explore the land of the Bible and recover the locations of biblical cities that, in many cases, had been lost for millennia. Although they were mainly occupied with exploring ruins located outside major cities, Robinson spent significant time making observations in Jerusalem during his stay there. Today scholars still associate his memory with three major “discoveries”1 in the city, the most famous of which is undoubtedly the spring of an arch which continues to be called “Robinson’s Arch” in his memory.

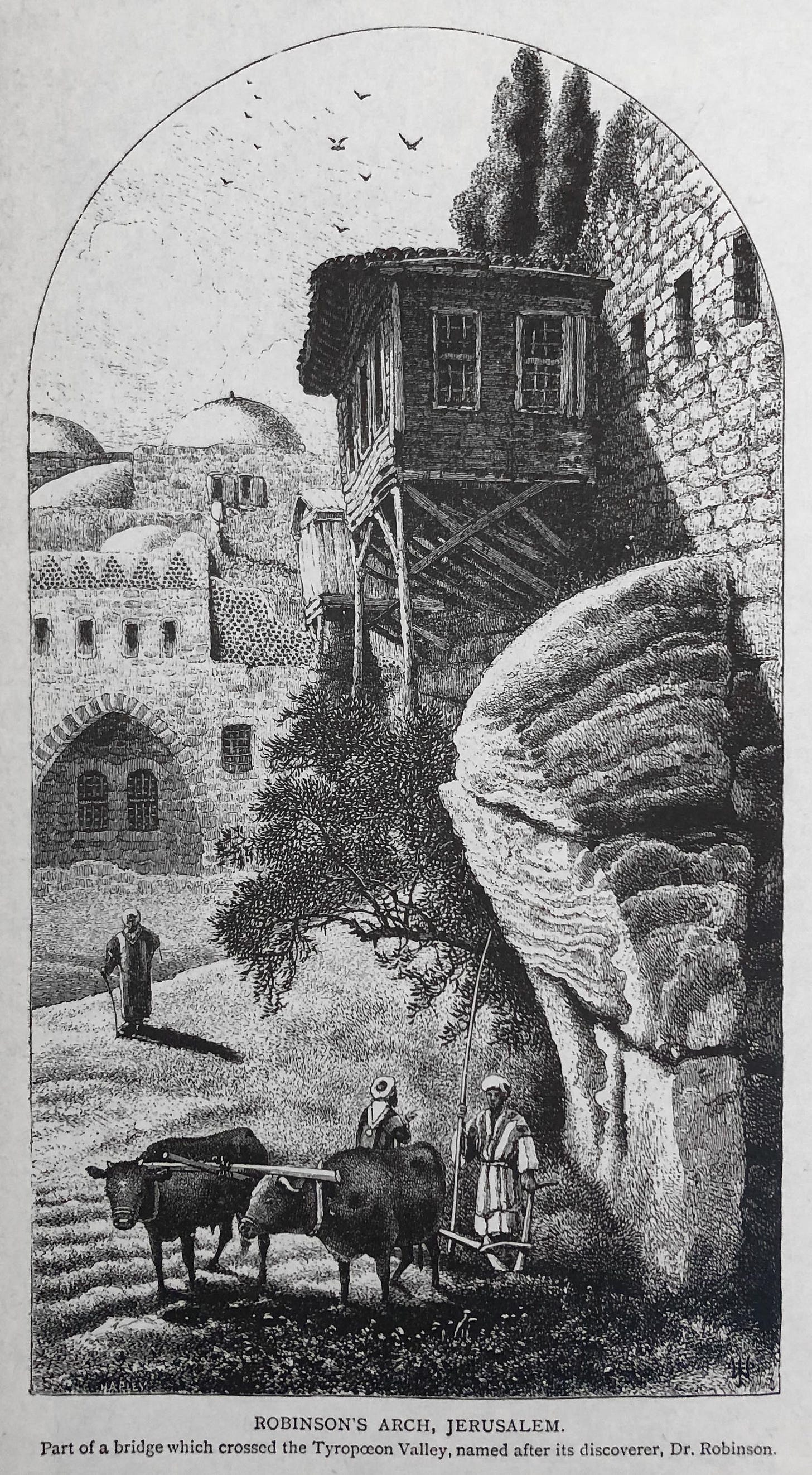

If you have visited Jerusalem, chances are good that at some point you stood underneath this line of projecting stones on the southwestern corner of the Herodian Temple Mount walls. Today the arch is understood to have been part of a monumental stairway that led down from the Temple Mount into the valley below. That interpretation, based on excavations that took place following 1967, is quite different from Robinson’s original theory about the arch which transformed it into his architectural namesake. In this edition of the newsletter, I want to review some forgotten details in the story of Edward Robinson’s most well-known contribution to the topography of Jerusalem.

Robinson Stumbles upon an Arch

In his typically meticulous journal entry for Monday April 16th, 1838, Robinson describes walking through the streets of the Moroccan Quarter to the area of its nearby agricultural fields. Here he mused briefly over a row of stones projecting from the wall of the Noble Sanctuary at ground level:

“The stones in the lower part of the wall of the area at the S. W. corner, are of immense size; and on the western side, at first view, some of them seem to have been started from their places, as if the wall had burst and was about to fall down. We paid little attention to this appearance at the time; but subsequent examination led here to one of our most interesting discoveries.” (BRIP I:351; emphasis mine)

In a later entry, Robinson discusses the significance of these stones. It is worth quoting the following paragraph in full in order to make several observations:

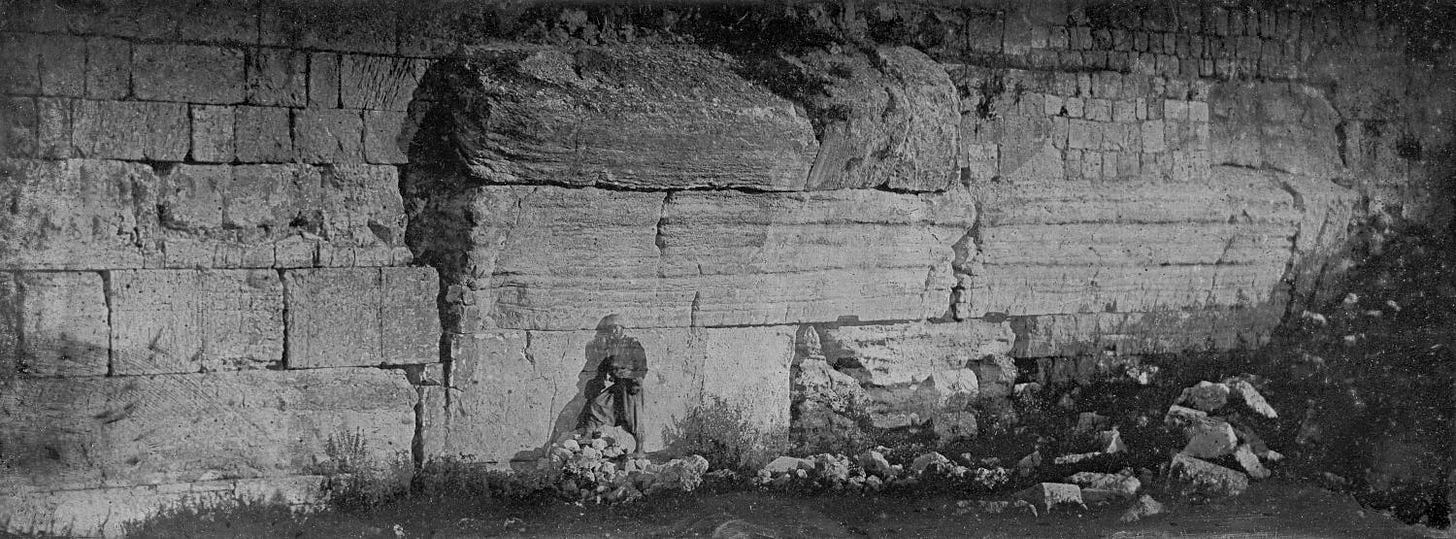

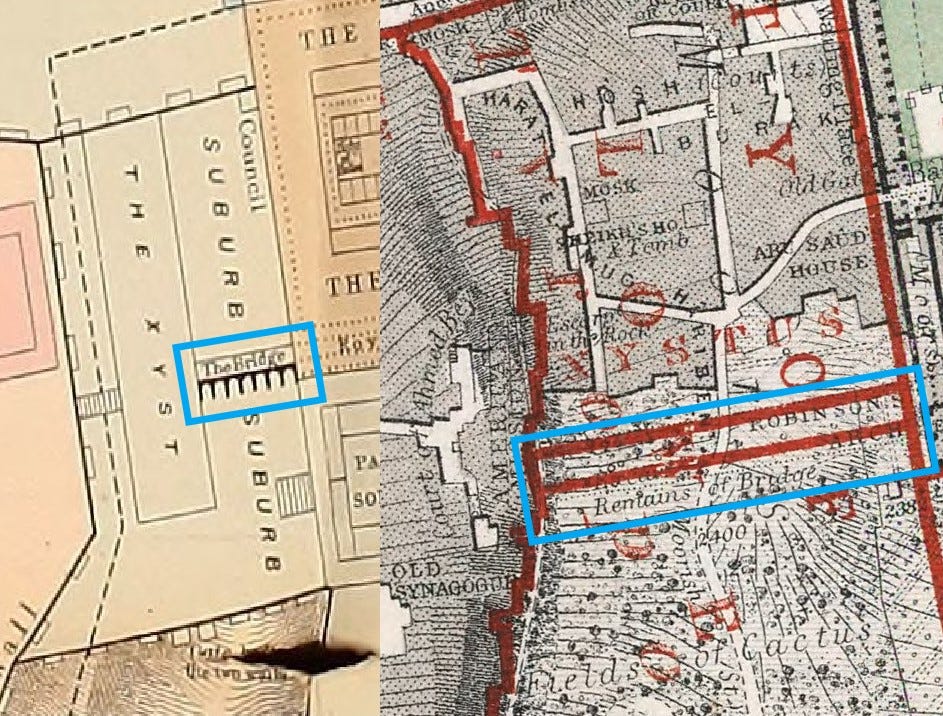

"I have already related in the preceding section, that during our first visit to the S. W. corner of the area of the mosk, we observed several of the large stones jutting out from the western wall, which at first sight seemed to be the effect of a bursting of the wall from some mighty shock or earthquake. We paid little regard to this at the moment, our attention being engrossed by other objects but on mentioning the fact not long after in a circle of our friends, we found that they also had noticed it; and the remark was incidentally dropped, that the stones had the appearance of having once belonged to a large arch. At this remark a train of thought flashed upon my mind, which I hardly dared to follow out, until I had again repaired to the spot, in order to satisfy myself with my own eyes, as to the truth or falsehood of the suggestion. I found it even so! The courses of these immense stones, which seemed at first to have sprung out from their places in the wall in consequence of some enormous violence, occupy nevertheless their original position ; their external surface is hewn to a regular curve; and being fitted one upon another, they form the commencement or foot of an immense arch, which once sprung out from this western wall in a direction towards Mount Zion, across the Valley of the Tyropoeon. This arch could only have belonged to which according to Josephus led from THE BRIDGE, and it this part of the temple to the Xystus on Zion ; proves incontestably the antiquity of that portion of the wall from which it springs.” (BRIP I:424-425)

Here Robinson tells us what he believed to be the significance of his contribution regarding this arch, and it is not that he claimed to be the one who discovered it.2 Other westerners who had passed through Jerusalem (and undoubtedly, many locals over the centuries) had already noticed it and also surmised that it had formed the beginning of an ancient arch.3 In fact, he tells us that if he were not informed of the curved stones by others, he may never have had reason to return to the spot. Rather, Robinson believed his innovation was found in his interpretation of the arch, that it constituted a long-lost bridge mentioned by Josephus which ran from the Herodian Temple Mount across the Tyropoeon Valley (Central Valley) to the Western Hill.4

For readers who may not be familiar with this passage in Josephus, here is how the Jewish historian describes the four western entrances to the Herodian Temple Mount in his own day. I have bolded the portion discussing the entrance that led Robinson to his interpretation.

“In the western part of the court (of the temple) there were four gates. The first led to the palace by a passage over the intervening ravine, two others led to the suburb, and the last led to the other part of the city from which it was separated by many steps going down to the ravine and from here up again to the hill….” (Antiquities of the Jews XV.410)

Robinson repeated and fiercely defended his idea in future publications, including articles in the journal Bibliotheca Sacra which he founded. His continued tenacity in the matter probably accounts for why a toponym with his name was created for the arch. For example, in Later Biblical Researches in Palestine, the publication of his second journey to the Holy Land with Eli Smith in 1852, he writes a long and staunch defense of his interpretation that includes the following excerpt:

“…so strongly does the massive fragment of an arch yet remaining suggest of itself such a bridge ; and so thoroughly does it correspond in character and position with the notices of Josephus ; that all those travellers who may be regarded as the best judges on such a subject, artists, architects and engineers, and who have as yet made public their views, have with one voice united in identifying this arch with the bridge of Josephus.” (1856:224)

After the name “Robinson’s Arch” became attached to the line of projecting stones, it was naturally assumed that Robinson had claimed to be its discoverer. Already in 1868, Rob Roy, a visitor to Charles Warren’s excavations in front of the bridge (see below), wrote that the stones “…by their curved edge projecting, show that once an arch was there. Dr. Robinson was the first traveller to remark this, so it is called “Robinson’s Arch.”5 Since Robinson was indeed the first person to write about it extensively, this shift is somewhat understandable but incorrect.

Robinson’s idea that the arch could be connected with the bridge mentioned by Josephus benefitted from early archaeological excavations that seemed to confirm his claim. In 1865, just two years after Robinson died, the British Royal Engineer Charles Wilson conducted The Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem and created the first “scientific” map of the city which included accurate elevations above sea level. One little-discussed aspect of this project was a series of shafts Wilson’s team sunk in 14 places throughout the city. One of them was carried out to a depth of 37 feet in front of Robinson’s Arch in an effort “to try and discover one of the piers” (Wilson 1865:75). The team finally hit a wall made up of masonry blocks oriented in the same direction as the Haram wall which they suggested could be the western face of the pier.

Two years later, another British Royal Engineer named Charles Warren came to Jerusalem as an official member of the newly established Palestine Exploration Fund. He also sunk shafts in the area of Robinson’s Arch (many more than Wilson) and, after some initial hesitation, claimed to have discovered the first pier of the bridge. He wrote in a letter to the PEF that “The discoveries of the pier of Robinson's Arch and the fallen arch stones have created no small stir in Jerusalem ; and all classes wishing to go down to see them” (PEFQst 1870 Supplement:57).

Summarizing the energy generated by Warren’s contribution to Robinson’s theory, W. Simpson wrote in 1868:

“Dr. Robinson's first and most natural conclusion, that this arch had been a bridge, was doubted by some of the highest authorities upon the topography of Jerusalem. But when Mr. Warren sunk a shaft at this place and came upon the pier which supported the other end of the Arch, every doubt was set at rest. A fact was attained and a point settled.” (PEFQst I:46)

Popularization of Robinson’s Arch as “THE BRIDGE”

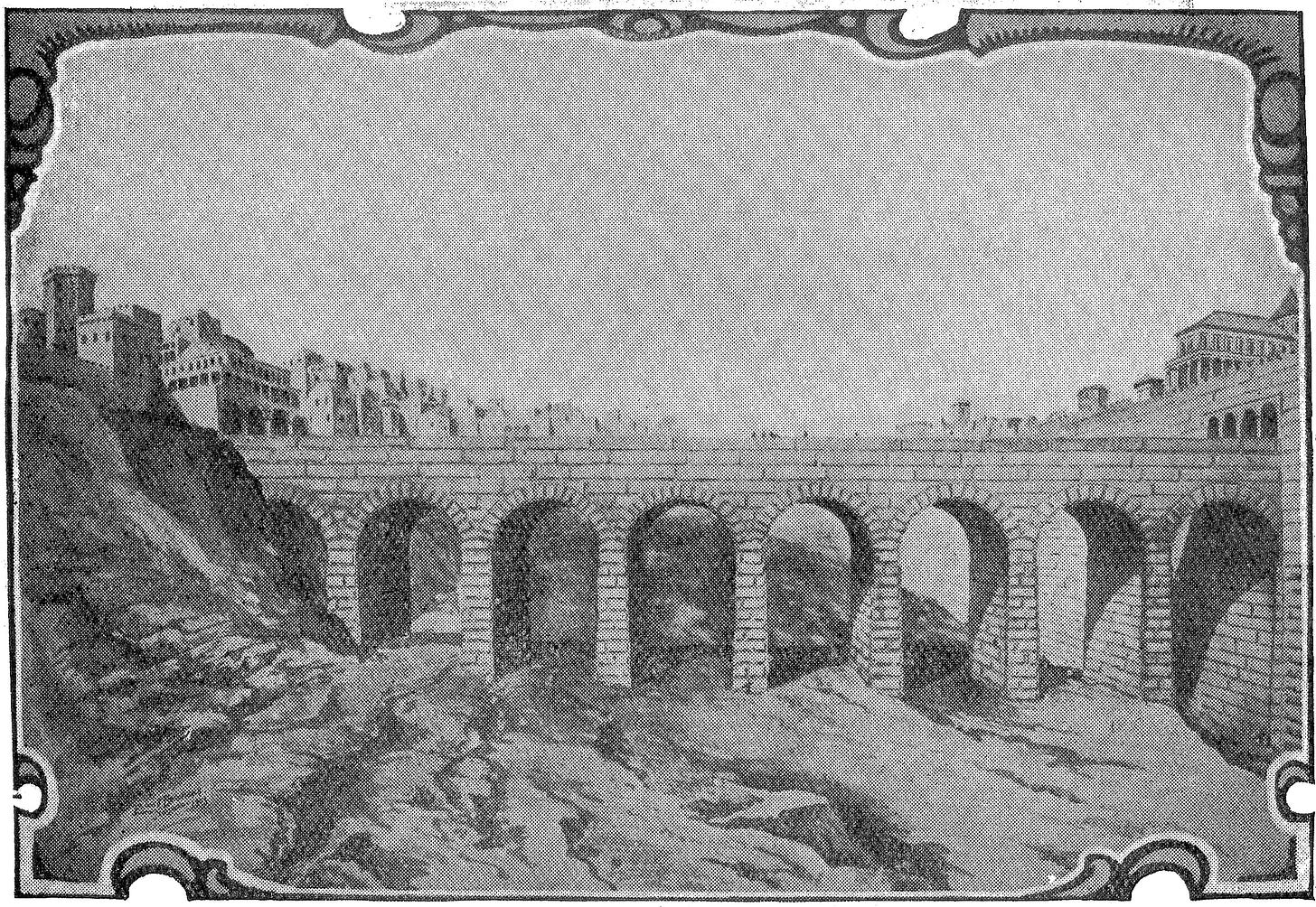

It is worth perusing some historical sources to see just how widely accepted Robinson’s theory about the bridge became during the 19th and 20th centuries. Several models of Jerusalem from that time demonstrate the adoption of Robinson’s bridge. This can been seen clearly in the model of Johann Tenz which is kept at the Christ Church museum just inside Jaffa Gate (see photo below). It is also shown in at least two models built by Conrad Schick, the 19th-century German architect and explorer. One is kept in the basement of the Schmidt Schule in East Jerusalem and the other in the small museum of the German Protestant Institute of Archaeology in the Augusta Victoria. The supposed bridge is also mentioned in guidebooks and Bible dictionaries, shown on a number of maps, and of course was the subject of discussion in scholarly literature.

Although Robinson’s theory was very popular, there were some naysayers. John Simons, in his masterful 1952 book Jerusalem in the Old Testament, offered compelling reasons to reject Robinson's idea.6 Robinson's most vocal opponent in his own day was George Williams, who served as the Chaplain to Bishop Alexander at Christ Church. His 1845 book The Holy City was, in many ways, a response to Robinson’s work on the topography of Jerusalem. Williams pointed out the fact that no piece of the bridge had been found on the western side of the Central Valley where it should have terminated at the Western Hill. He also offered the compelling topographical argument that such a bridge would have been too low in elevation to do much good if the main purpose was to lead to the much higher palace area as Josephus says. But such dissent did not sway the opinion of the field away from Robinson.

The End of an Era

After the events of 1967, which included the forced eviction and demolition of the Moroccan Quarter, the entire area adjacent to Robinson’s Arch was systematically excavated for the first time by Benjamin Mazar and Meir Ben-Dov.7 They uncovered the same pier that had been found a century prior by Wilson and Warren. Influenced by Robinson's theory that was still dominant, Mazar and Ben-Dov fully expected to uncover the remaining piers of the bridge.8 However, it soon became clear that they simply did not exist.

What they unearthed instead was evidence that, a large stepped walkway landed on the first pier, bent toward the south, and led into the valley below over several flights of steps. This entrance to the Herodian Temple Mount still found a reference in Josephus,9 but it surprisingly could not be the bridge on which Robinson had famously staked his claim. In this way, a majority view and archaeological dogma that featured across diverse genres of sources about Jerusalem for 130 years was eviscerated.

Processing their tendency to assume Robinson’s theory in the face of evidence to the contrary, Ben-Dov later wrote:

"In retrospect, it is difficult to understand why the investigators (ourselves included) clung with such tenacity to the notion of a horizontal [bridge across the valley] which is precisely the opposite of the written evidence." (1982:131)

Perhaps this is at least partly not so difficult to understand when we consider the components that made up the interpretation of the bridge: the charismatic figure of Edward Robinson, the apparent early archaeological confirmation, and the ways Robinson’s theory had been baked into so many sources related to the study of ancient Jerusalem.

Today, although Robinson’s name remains attached to the arch, his original theory and its dominance in the literature has mostly faded from memory. With hindsight, we can see that the models, maps, dictionaries, guidebooks, and sketches that adopted Robinson’s interpretation were only projecting his imagination onto the landscape of ancient Jerusalem. Perhaps this example may help us to hold current prevailing ideas about the city with an open hand, even the most sacred that have been cast by scholarly giants.

Discoveries is in quotes here because, although he is widely credited this way, he is probably better thought of instead as a popularizer. The other two “discoveries” are the Siloam Tunnel, which he and Smith were allegedly the first to crawl through in its entirety, and the line of the so-called Third Wall of Josephus.

In a later passage, Robinson notes that Bonomi and Catherwood had already seen these stones in 1833 and understood that they were the spring of an arch. But he writes that they “had no suspicion of their historical import” (BRIP I:427n1).

In his fantastic biography of Robinson, Jay G. Williams notes that even the idea the Robinson innovated may not be correct. The missionary and scholar H. A. Homes claims to have not only led Robinson to the very spot on that day in 1838 but also to have told him of “the probability that it was the bridge mentioned in history as going from the temple to Mount Zion.” He continues, “Ever after I had much personal satisfaction in reflecting that I had been the instrument in introducing Dr. R to a ruin of so much importance.” (Williams 1999:234)

See also Ben-Dov 1982: “Among the salient and fascinating finds [Robinson] uncovered in his work here were vestiges of a huge destroyed arch, which he first discerned from telltale signs in an otherwise undistinguished vegetable plot in Jerusalem” (121; emphasis mine).

See pages 423-428.

To the best of my knowledge, this excavation remains unpublished aside from popular books and preliminary reports.

After the second excavation season, Mazar wrote: “Between this [royal] stoa and the palaces of the Upper City to the west, Herod built a bridge – of which only ‘Robinson’s Arch’ remains today...” (1969:3; see also Plate IX).

This is the fourth entrance listed in the quote from Josephus’s Antiquities above

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous editions of this newsletter or follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.