Summary and Analysis: New Article Suggests a Sluice Gate Was Used to Control Water Levels in the Siloam Tunnel

If correct, this study claims to have identified the oldest sluice gate in the world, but the suggestion is not without significant problems

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

I recently saw Ticia Verveer share a new and interesting open-access article about the Siloam Tunnel which appeared in Archaeological Discovery: “A Sluice Gate in Hezekiah’s (Iron Age II) Aqueduct in Jerusalem: Archaeology, Architecture and the Petrochemical Setting of Its Micro and Macro Structures” by Aryeh Shimron (Geological Survey of Israel) and Vitaly Gutkin and Vadimir Uvarov (Center for Nanoscience and Nanotechnology at Hebrew University). I had a chance to read through the article and felt compelled to present a summary and analysis of it here.1

Summary

Shimron et al argue that a previously undetected sluice gate was used to control water levels in the Siloam Tunnel which was hewn as part of King Hezekiah’s preparations for the coming Assyrian campaign in the late 8th century BCE.2 If they have correctly identified this gate, it would apparently be the oldest known example from the ancient world (81). The gate was wooden and has long since deteriorated, but evidence of its presence is suggested by the remains of four nails that were found hammered into the walls of the tunnel (photo below). The nails were tested and shown to be made of wrought iron (95-97). They also contained traces of petrified wood that may be cedar and are understood by the authors to be remains of the sluice gate (98-99).

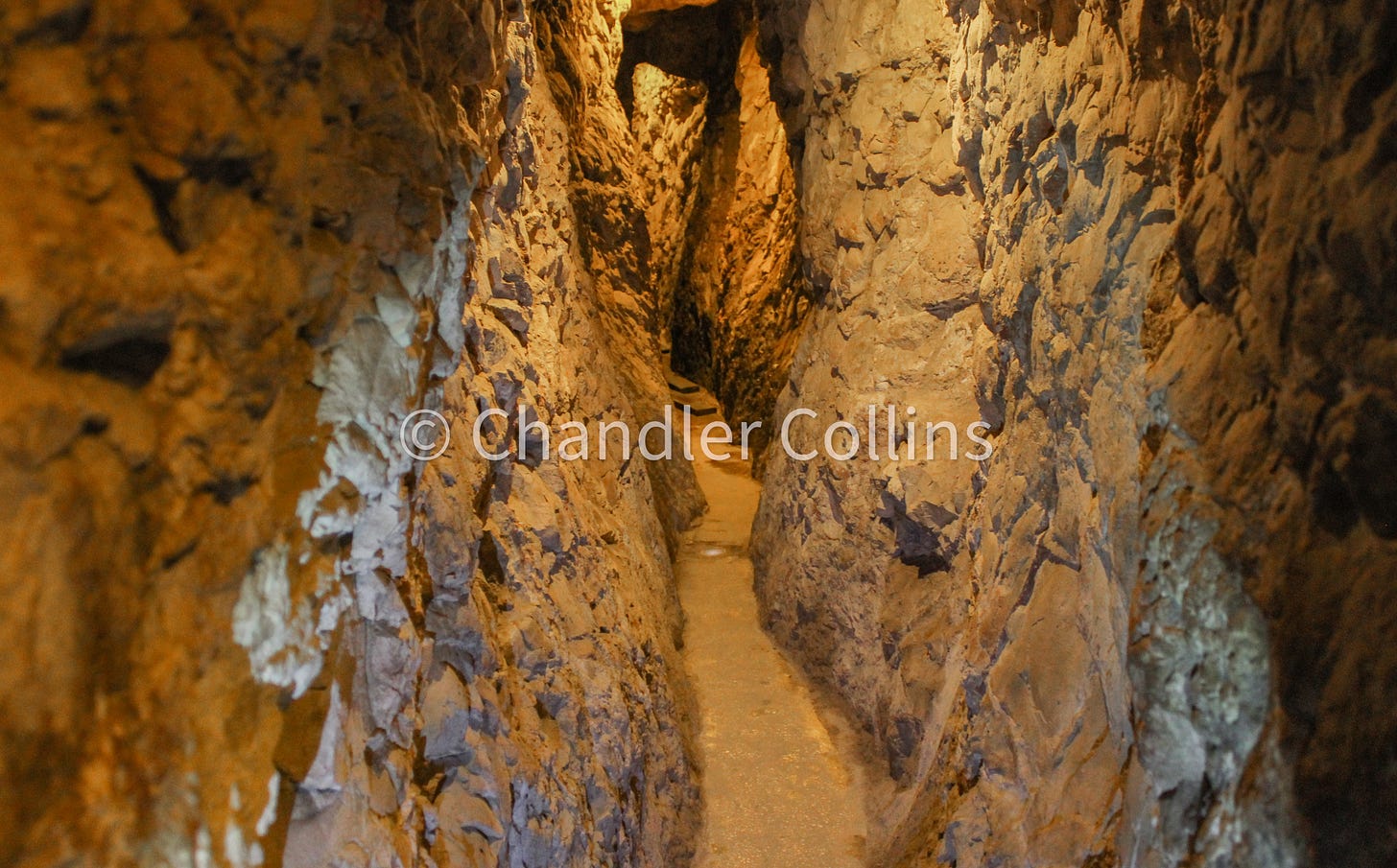

The proposed area of the sluice gate is exactly where the tunnel begins to rise dramatically toward its southern end vs. the northern portion of the tunnel which is much lower. Many who walk through this area are struck by the dramatic change in the height of the ceiling (I have to walk parts of the tunnel bent over and at this point can stand up comfortably). This theory would account in part for the sudden rise of the ceiling. Shimron et al also believe there is evidence nearby that the northwestern wall was being deliberately shaped for the “emplacement” of the Siloam Tunnel Inscription.3

The authors note that the bedrock on either side of the tunnel in the area of the gate is not symmetrically shaped for the mounting of the sluice gate (92). They suggest some later activity in the area may account for how the stone was reshaped after the Iron Age. There was some very interesting evidence of such activity from the Mamluk Period found in mortar on the nearby ceiling (91-92, 94; see below).

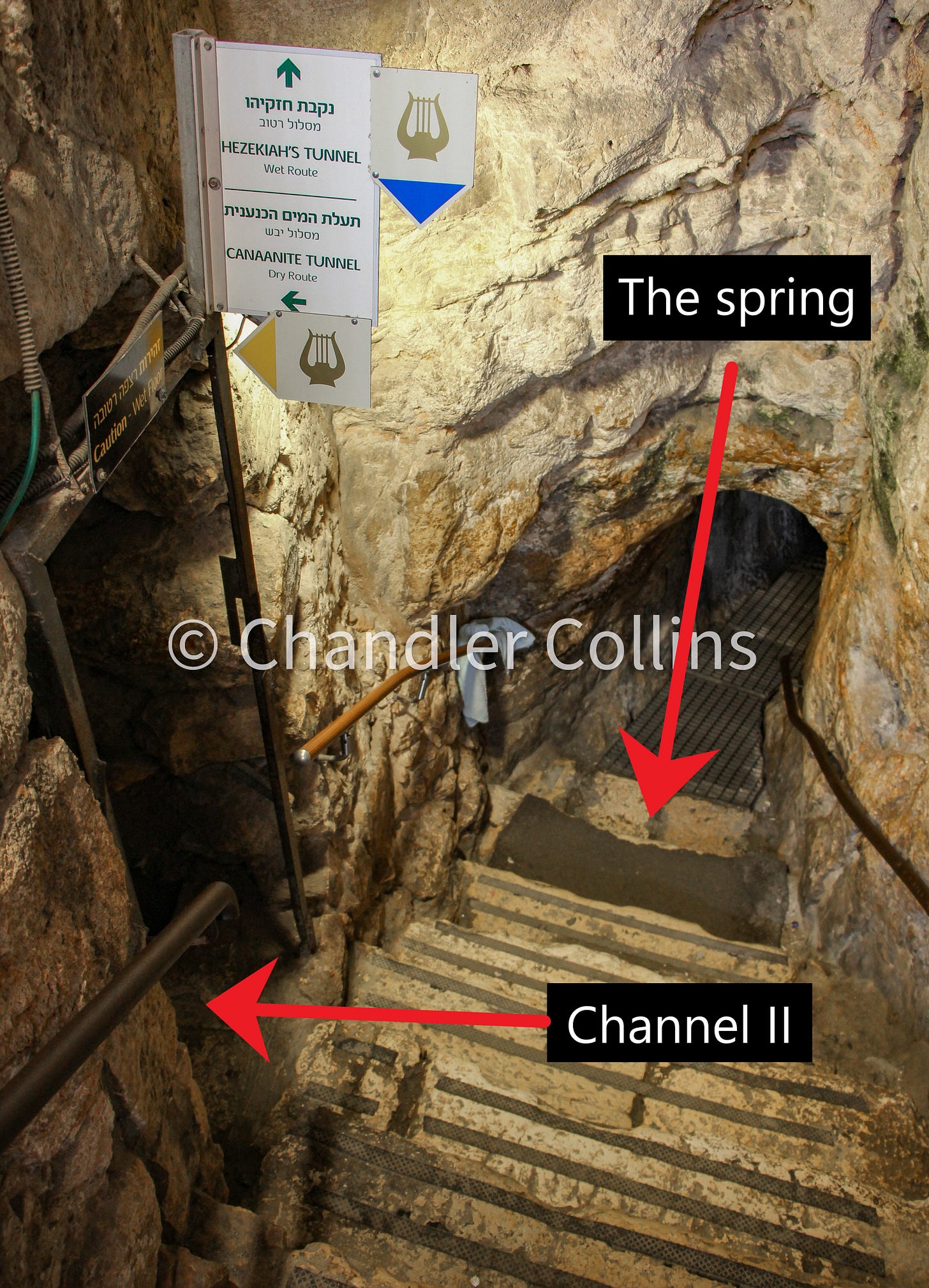

Shimron et al interpreted nearby remains on the ceiling as a bolt which may have been used to hold the cable that operated the gate. Remains of what they understand as calcified wool was found on the ceiling next to the bolt, suggesting that the cable was made of that material. It would have needed to run along the ceiling of the Siloam Tunnel to a shaft to the surface some 30 meters (98 feet) away. There they suggest the cable ran either to the surface or to the inside of Channel II where the sluice gate could be operated safely from the inside the city walls (81). The cable needed to be ca. 50 m (164 ft.) long in order for this to be possible (80-81).

The study also revealed unrelated but interesting details about the quality of the spring water. Chemical analysis of the nails and the tunnel in areas close by showed changes in the water over time. This includes a rise in the pH levels perhaps due to sewage from Jerusalem’s urban expansion (in the 19th century and following) and chlorine that was added to the water supply in the 1970s (100, 106, 109).

Now we come to some important issues related to the interpretation of the sluice gate within the context of the Jerusalem water system. The authors reason that the gate was needed because the Siloam Tunnel sits at a lower level (ca. 635 m. = 2,083 ft. above sea level) than other key areas of water access closer to the spring (ca. 637 m. = 2,089 ft.). They argue that the objective of adding a sluice gate was to raise the water level in the Siloam Tunnel in order to inundate the older elements of the water system that sat at a higher elevation level. The article pinpoints three key parts of this system which were served in this way: Channel II, the Round Chamber, and the bottom of Warren’s Shaft.

Channel II, an older Canaanite tunnel in Jerusalem’s water system, sat at a higher elevation than the Siloam Tunnel (ca. 2 m. = 6.5 ft. higher). Before the spring water flow was diverted into the Siloam Tunnel in the 8th century BCE, it probably emerged from the bedrock and, with nowhere else to go, entered Channel II where it would flow southward.4 From the Middle Bronze Age until the 8th century BCE, Channel II diverted the spring water southward along the Kidron Valley where it may have been used for irrigation or drinking.5 Later in the 8th century, Channel II was extended further south (see below). The opening up of the Siloam Tunnel at a lower elevation diverted the water away from Channel II.

A side channel coming off of Channel II, known as Channel III, brought water into a rock-cut Round Chamber that was apparently used as a bucket-drawn water reservoir by Jerusalem’s inhabitants during the Middle Bronze Age and possibly until the 8th century BCE.6 The authors of the article point out that after the cutting of the Siloam Tunnel, the diverted water would not have filled this important chamber.

The article’s authors reason that after the Siloam Tunnel was cut, water also would not as easily have reached the area at the bottom of Warren’s Shaft. Although the spring water flowed close by the area under the shaft, the opening up of the Siloam Tunnel would have had an impact on the amount of water that ended up there, limiting what could be drawn up by bucket. This assumes-as Shimron et al argue do-that the shaft was used to draw water from the top (see below).

So, to recap: the authors of this article argue that after the Siloam Tunnel was hewn and the spring was diverted there, water would no longer bubble up under sufficient pressure in order to rise 2 m. in elevation and (1) enter Channel II and run south along the Kidron Valley, (2) fill the Round Chamber via Channel II and III, or (3) sufficiently enter the area at the bottom of Warren’s Shaft so that Jerusalem’s inhabitants could draw water by bucket from the top.

What is their solution to these perceived issues? A sluice gate in the Siloam Tunnel that could temporarily raise the water level and allow the other elements of Jerusalem’s water system to fill and continue to be used:

“The king’s engineers were well aware that such a diversion [into the Siloam Tunnel] would significantly lower the water level in the northern water conduits and reservoirs (the cave beneath Warren’s Shaft, the Round Chamber and Channel II, Figures 2-4). This would mean cutting off most of the water from the bulk of the city’s population. In order to overcome such a potentially fatal threat a mechanism was needed that would allow the water level in the tunnel to be raised and lowered as and when needed. For this purpose two major precautionary steps were taken prior to allowing water flow through the tunnel: 1) the many voids in the newly exposed highly fractured and karstified tunnel walls were sealed with hydraulic plaster up to an average height (~2 m) of the tunnel ceiling… and 2) a movable damming source was constructed at a favourable location in the tunnel.” (Shimron et al 2022:72)

An ingenious solution but one that has some significant problems.

Analysis

Shimron et al are to be commended for locating previously unknown remains in an area that has been surveyed by so many scholars. Their fascinating detailed chemical analysis of the Siloam Tunnel has given us new data to work with. However, I do not believe the study justifies the author’s proposed rationale for or the supposed physical setting of the sluice gate. The biggest problem is evidence suggesting the older elements of Jerusalem’s water system ceased to be used after the Siloam Tunnel was excavated. Hence if a sluice gate was installed in the tunnel, it could not have been for the reasons suggested in the article.

For example, when Ronny Reich and Eli Shukron excavated near the Round Chamber (part of which was originally discovered and excavated by Parker and Vincent in 1909), it was found to be full of 9th-8th century BCE debris, including bullae and fish bones, with an 8th century BCE house built on top.7 Therefore, this space could not have continued to be used as a water reservoir in the 8th century when the Siloam Tunnel was hewn. The evidence suggests that it was deliberately put out of use.

As for Channel II which (via its tributary Channel III) brought water into the Round Chamber, there is also evidence that it went out of use when the Siloam Tunnel was hewn. In Reich and Shukron’s partial excavations of the channel, they found pottery dating to the 8th-7th centuries BCE in two layers on its floor.8 They suggest this indicates the date that Channel II had ceased to be properly maintained, so it was no longer used.

We can also reason that Channel II went out of use based on its termination point. A tunneling operation in the 8th century BCE-but probably earlier than the cutting of the Siloam Tunnel-extended Channel II southward toward the convergence of the Central and Kidron Valleys. It terminated at the southern end of the Southeastern Hill near where the later Pool of Siloam was built. Although a successful effort, the newly expanded channel was not used for long, perhaps because it was badly in need of repair and partially covered by massive boulders that were hard to move. For whatever reason, Jerusalem’s leaders opted to hew out the Siloam Tunnel in order to divert water from the spring southward instead. Because both Channel II and the Siloam Tunnel terminated at essentially the same place, it is hard to understand why Channel II was needed at all after the hewing of the Siloam Tunnel.

As for Warren’s Shaft, I personally doubt that it was ever used to draw water, at least not in any substantial way. This is mainly due to its shape which shows that it was naturally formed and not manmade.9 In 1952 the historian of Jerusalem John Simons wrote,

“The very inadequate shape of the cistern-shaft, one of the most vital parts of the project, is surprisingly disappointing, considering how much patience and energy was bestowed on the work as a whole.”10

If the shaft was used to draw water with a rope and bucket, we may ask with Simons why its sides were not more deliberately smoothed to better facilitate it. The deeply engrained presupposition that the shaft was used to draw water seems to be a hold-over from a time when much less about Jerusalem’s water system was known and great emphasis was placed on the function of the shaft. Recent excavations and analysis suggest an entirely new context for the water system which should deprive Warren’s Shaft of its former prestige.

Some scholars believe that a wall contemporaneous with the Siloam Tunnel was built in front of the area below Warren’s Shaft to prevent water from being diverted there and to ensure that it more directly flowed into the Siloam Tunnel. On this view, Warren’s Shaft is seen as no more than a temporary means to remove stone chips from the Siloam Tunnel as it was being hewn (the well-known stepped entrance leading to the spring today was not cut until much later).

Several other issues complicate the interpretation presented in this article. For example, the authors do not provide direct dating evidence for the sluice gate. Hinting at this problem, they write “The device, if proven to date to Iron Age II, is—to the best of our knowledge, the oldest sluice gate known and now recorded” (108, emphasis mine). They suggest an 8th century BCE date for the gate based on indirect evidence: the dating of the high water lines ca. 1.5 m. above the tunnel floor. Remains embedded within the hydraulic plaster and later deposits upon it, at the level of the water lines, were dated to between the 8th-4th centuries BCE (79). This leads the authors to suggest that there was water level control in the tunnel during this period (83). However, they cannot demonstrate a connection between the evidence of water control and the remains of the supposed sluice gate by direct dating of the nails or other nearby remains. It is also unclear why water never control would have been needed after Jerusalem’s destruction in 586 BCE. Perhaps another explanation would account for these water lines in the Siloam Tunnel.

Another potential issue is the location of the sluice gate and manner it would have been mounted. Considering that in the proposed location the gate would have needed to contain the pressure of water flow for nearly the entire tunnel, one wonders if just four nails on part of the frame were enough to hold it in place. Perhaps construction of a sluice gate closer to the spring would have better suited the objectives laid out in the article. The authors also mention that the sides of the tunnel in the area of their sluice gate lack symmetry. This seems strange given the ability shown by the Judahite engineers to cut the tunnel effectively. Surely they could have shaped the tunnel walls to hold the gate’s frame securely in place. As Shimron et al reason, maybe this area was altered later, but that is so far a suggestion without evidence.

It also seems peculiar that the shaft to the surface, through which the supposed wool cable ran that operated the sluice gate, was 30 m away. Were the engineers not capable of cutting a shaft from the area of the gate upwards in order to have more direct control over its operation? The authors make much of the fact that the location of the shaft to surface was near the point where the Siloam Tunnel and Channel II almost converge (80-81), but it is not clear what made this convergence so important or why it would have dictated the location of the sluice gate 30 m. away.

Conclusion

The ideas in this article were fascinating to read and consider. In the end I am unable to accept the understanding of the water system presented by the authors into which the proposed sluice gate was integrated. If, as Shimron et al suggest, the sluice gate was in use from the 8th-4th centuries BCE, then we must search for a new historical rationale for creating such a gate. It could not have served the older parts of the water system that went out of use after the Siloam Tunnel was hewn. Might there be another valid reason for building a sluice gate in the tunnel?

I am unsure what to do with these new and fascinating remains discovered in the Siloam Tunnel. Might there be an entirely different way to account for them? Very interestingly, mortar samples on the ceiling near the area of the supposed sluice gate contained charred wood that was dated to the Mamluk Period. The mortar also included traces of slag and metal (91-92, 109). Perhaps remains from this area, which shows such clear evidence of human alteration, was in some way related to this previously unknown evidence of smelting in the Mamluk Period.

Time and further research may help scholars better understand these obscure remains in the Siloam Tunnel. Even if unlikely, it was interesting to read yet another proposal related to this famed tunnel about which so much has already been written.

This is another discussion for another day, but I find the majority understanding (and in many ways, archaeological dogma) that Hezekiah undertook the Siloam Tunnel project as part of his preparations for Sennacherib’s campaign in 701 BCE hard to accept. The hewing of the Siloam Tunnel through hard Mizzi Ahmar limestone not only would have taken years to complete, but in the end, it terminated in nearly the same place as Channel II after it was extended southward sometime in the 8th century BCE. A supposed rush job only to divert water to the same place it was already going makes little sense to me (replacing one channel that was falling into disrepair with another one seems like a better idea). Both channels have also been shown by recent excavations to be safely protected inside the 8th century BCE city walls (Reich and Shukron 2021:171-214). In brief, I believe there are other ways to understand both the archaeological remains and biblical references to Hezekiah’s waterworks without folding the Siloam Tunnel into his preparations for the siege.

The authors appear to erroneously believe the Siloam Tunnel Inscription was written on a “tablet” that was inserted into a hole in the tunnel:

“We hypothesise [sic] that this surface was being prepared to receive the emplacement of the well known Hezekiah’s tunnel inscription tablet…Should this indeed have been the objective it was obviously not carried out as the surface does not appear to have been completed and the inscription tablet was eventually inserted into the SE wall within a few meters of the tunnel’s southern exit. We point out that a similar preparation for the emplacement of a tablet was done near the junction of Channel IV and the Rock-cut Pool…” (94; emphasis mine)

The present cave where the spring emerges seems to have been hewn out in the 8th century BCE when the Siloam Tunnel was being excavated. Reich and Shukron assume that the level of Channel II is the same level that water would have emerged from the spring during the Middle Bronze Age (Reich and Shukron 2021:189, 212-213). However, Gill assumes the water was artificially raised to reach Channel II (1991:1467).

Because of lack of evidence, scholars now doubt the longstanding idea that Channel II had “windows” that were used for irrigation (as illustrated in this drawing). Reich and Shukron suggest there may have been a Middle Bronze Age pool in the Kidron Valley while noting that such evidence has not yet been uncovered.

So interpreted by Ronny Reich (2021).

They estimated around 250 cubic meters (= more than 550,000 lbs) of debris sat inside the rock cut area (Reich 2021:199).

Simons 1952:167-168.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous editions of this newsletter or follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.

Raising the level of the flow of the water was a problem decades ago, when youth at the southern end would, for political reasons block the flow which then would raise the level when youngsters were walking the tunnel from the northern entrance, thus endangering lives.

Great read ! I was totally unaware of the sluice theory associated with the Siloam tunnel. Your summary and analysis were very helpful. Equally helpful were your explanations about the various channels and water system as a whole. Thanks so much Chandler. I look forward to reading your analysis and conclusions about the Siloam tunnel. God bless. Hope you are well.