Summary and Review: Jerusalem 1900, The Holy City in the Age of Possibilities by Vincent Lemire

This pioneering book invites readers to reconsider the character and trajectory of Jerusalem at the turn of the 20th century

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

In Jerusalem 1900: The Holy City in the Age of Possibilities, Vincent Lemire is at pains to convey the character of Jerusalem in the decades around the turn of the century. That is to say, he means to explore the state of the city before World War I, British occupation, and the rise of competing nationalisms which color all understandings of Jerusalem today. He argues that the decades around 1900 comprise a unique moment in the city’s history that is virtually unknown. On the precipice of decisive—but totally undetermined—shifts wrought by World War I, the Holy City found itself teetering unknowingly in “the age of possibilities.” Lemire’s book invites us to deliberately remove our hindsight and sit with Jerusalem in 1900 CE. While it may be tempting to reduce this special moment in time to “a simple, enchanted parenthesis,” (11) Lemire hopes that revisiting these decades of Jerusalem’s legacy can be an influence toward a shared sense of its future (10-12).

Sources and Methods

An important contribution of Jerusalem 1900 is its historical methodology. Lemire writes that our collective forgetting of Jerusalem’s age of possibilities results from lack of access to the Ottoman archives (known only to the few researchers who can read Ottoman Turkish). Jerusalem’s municipal archives were also not made available until 1993 and are still just beginning to be integrated into research (7; 103).

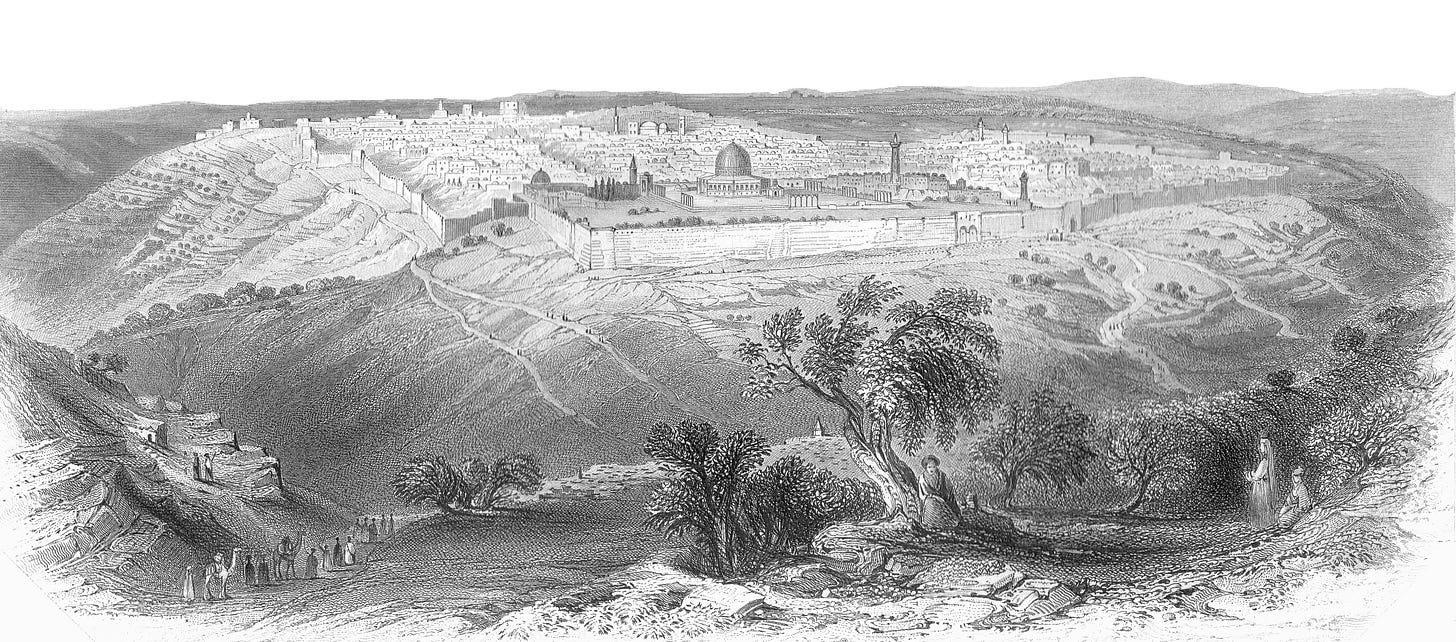

In the absence of direct evidence of Jerusalem’s Ottoman-era administration, historians have used the available source material, mainly the literature of western travelers, to write a history of this period. The majority of these visitors spoke neither Arabic nor Turkish and stayed in the city only temporarily. Their accounts are focused largely on religious architecture or archaeological ventures rather than the daily life of Jerusalemites. According to Lemire, taking these writings at face value in order to reconstruct a social history of Late Ottoman Jerusalem resulted in understandings of the city that were “shaky, uncertain, and…out of sync with local realities” (79).

He illustrates the problem with this method by imagining its application to other cities:

“What sociologist today would work on the population dynamics of Marrakesh on the basis of maps printed in travel guides published in France and aimed at tourists? What urbanist would research the dynamics of the real estate market in Paris on the basis of maps used by American, Chinese, or Japanese tourists, or on the basis of the guidebooks they used to find the locations of museums, hotels, department stores, and the Eiffel Tower? What kind of reality do these documents speak of? They are neither “incorrect” nor “lies,” but they do document a very specific reality: international mass tourism in Paris at the beginning of the twenty-first century. [These examples show] the gaping chasm that separates, particularly in Jerusalem, the city lived by its inhabitants from the city dreamed…by western visitors.” (34)

Lemire has spent extensive time studying archival material (10-11) and aims to correct this problem by fronting Ottoman-era municipal records, along with sources written by native Jerusalemites (e.g. Greek Orthodox oud player Wasif Jawhariyyeh, Jewish educator and politician David Yellin) and foreigners who paid close attention to the realities of the city (e.g. German architect Conrad Schick, British Consul John Dickson). He adds data from the studies of scholars who apply the same historical method throughout the book (such as Michelle Campos and Johann Büssow).

Administration

In contrast to prevailing ideas about Late Ottoman Jerusalem, this book presents a city that was well-integrated into the fabric of the Ottoman Empire. In chapter four, "The Scale of the Empire," Lemire profiles six of Jerusalem’s Ottoman governors who served in the decades surrounding 1900, all of whom spoke multiple languages and went on to hold other esteemed positions, including Grand Vizier (85-89). Far from being a backwater in the Ottoman Empire, two of the governors actually requested the post in Jerusalem, suggesting it was viewed with some prestige (80).

Lemire reviews technological advancements that took place during this time, such as those in the Jaffa Gate area described below, along with the development of a road network spanning from the coast to Transjordan, and a railway from Jaffa to Jerusalem (92-98). The so-called Lower Aqueduct, which supplied water to the Noble Sanctuary, was renovated and inaugurated on the Sultan's birthday in 1901.1 Residents of all faiths and backgrounds gathered to celebrate this occasion. A branch of the aqueduct ran to a newly built sabil (water fountain) at Jaffa Gate and also supplied water to the Jewish neighborhood of Yemin Moshe (98-101). In 1914, plans for the first tramway line in Jerusalem were also drawn up, although the project was never undertaken (119).

Chapter five explores the city’s municipality, formally founded in the 1860s, which is described as a competent, active, and diverse body, representing members of all faiths of the city (107-110). This section details the municipality’s administrative responsibilities, including issuance of building permits, garbage pickup, street cleaning, street light installation, assigning of street names, creation and maintenance of public parks, opening and funding the municipal hospital, and a number of other measures.

Shared Space and Time

A repeated emphasis throughout the book is that the divisions within Jerusalem as we know them today were not inevitable, and those that did exist were different than the ones we are familiar with today. They were also “due less to internal factors than to external geopolitical causes” (6). Lemire argues instead that the city was characterized by a collective sense of belonging.

Chapter six, “The Wild Revolutionary Days of 1908,” discusses the shared public space that developed on the west side of the city. In the decade following 1900, this public center of Jerusalem grew significantly along the Old City walls outside Jaffa Gate. Among other things, it came to include a newly erected municipal building, the public water fountain described above (which was also publicly funded), and a four-sided clock tower built above Jaffa Gate and lit by lanterns at night. The clock tower created a sense of public time for all Jerusalemites (130). Signs in numerous languages can be seen in photographs of Jaffa Street from this period.

A wooden pavilion built in 1912 by the newly founded Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts sat just across from Jaffa Gate in the midst of this space. Lemire reflects on a photograph of this building with its Jewish architectural motifs in the context of the shared Ottoman public center:

“…one last piece added an unexpected artistic dimension to the area around Jaffa Gate: a monumental wooden pavilion, topped by a crenellated tower about 10 meters high, constructed by the Bezalel School…to provide an exhibition and sale space for objects created by its students. As we look today at…this surprising pavilion, with its top frieze decorated with menorahs and other Hebrew symbols, and the proud founder Boris Schatz posing on the front steps, we understand that something really did happen in Jerusalem during those years, something that has escaped us until now.” (129)

The Four-Quarter System

The first chapter of the book, “The Underside of Maps: One City or Four Quarters?” is worth considering at length because it is such a helpful summary of the issue in just 24 pages.2 In this section, Lemire addresses the common division of the Old City into Christian, Muslim, Jewish, and Armenian Quarters which is widely understood to be an organic reflection of Jerusalem's architectural and social history. Lemire references a helpful but underused article by Adar Arnon at several places in this section.

This interesting chapter challenges the traditional four-quarter division by pointing out that there are no sources produced by Jerusalemites in the Ottoman Period that reflect it. Instead, Mujir ad-Din, the Jerusalemite qadi and historian who wrote at the beginning of the Ottoman Period, describes nineteen quarters of the city (28-29). Local sources in the 19th century describe as many or more! Lemire presents a map that shows Jerusalem’s quarters as they were simplified by the Ottoman government for administrative purposes, but even they fall into seven quarters, not four as might be expected (28).

If the modern four-quarter division of the city is absent in documents that reflect native understandings of Jerusalem in the Ottoman Period, how did it arise? Readers come to learn that it was the creation of western travelers and explorers who (1) lacked the language skills, curiosity, or time in Jerusalem to develop a more nuanced understanding of the city, and (2) were more interested in the major religious architecture of Jerusalem than its lived reality. First appearing in print in 1837, the four-quarter idea became widely used on maps as a means to simplify the complex city for other westerners (26).

This imagined division of Jerusalem along ethnic and religious lines was gradually imposed onto the city over the last century and today has become accepted as reality. The four quarters came to more accurately reflect the city after the British Mandate government officially accepted it (38). Lemire understands why this popular idea of Jerusalem gained traction in guidebooks but is surprised it was ever used by historians to describe social realities in the city (35).

He devotes a full chapter to this issue because it illustrates the value of prioritizing Ottoman sources over travel accounts. In contrast to the maps that chop the city into four quarters, Lemire produces the following statistics on the basis of the Ottoman censuses from 1905: “29 percent of Muslim families lived in the so-called “Jewish” quarter, 32 percent of Jewish families lived within the so-called “Muslim” quarter, and 24 percent of Christian families lived with in this same “Muslim” quarter” (27). One quarter (al-Wad) was so diverse that it was called by the German architect Conrad Schick, who lived in Jerusalem for more than 50 years, “a mixed quarter” (37-38).3

Lemire concludes: “At the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Jerusalem was characterized more by diversity than by separation of communities.” This exploration of the four-quarter system's history (and its implied separation) complicates assumptions about the Old City today.4

Conclusion

The conclusion of the book brings its discussion to bear on the city of our own day “as a point of departure for thinking of a possible shared future” (168). Lemire is eager to contribute to the trajectory of the city, a burden any author must feel when writing about Jerusalem. While he may be right that his “age of possibilities” provides a commendable framework for a shared Jerusalem, this connection is not really developed in the book. We may also question whether aspects of the “enchanted parenthesis” around the year 1900 were bolstered by specific historical realities that are unrepeatable today. Nonetheless, principles for governing Jerusalem in an equitable way can certainly be drawn from Lemire’s discussion of the Late Ottoman city.

If Jerusalem 1900 aims more broadly to highlight an underappreciated moment in the city's history and to build a compelling counternarrative about the nature of Late Ottoman Jerusalem, I think it has succeeded. For readers steeped in the current realities of Jerusalem, Lemire may as well be describing a city on the moon. Because his historical reconstruction diverges so widely from traditional and popular notions of Late Ottoman Jerusalem, some readers may find themselves redescent to accept it. However, the book presents important data points which support its overall thesis that we have overlooked a unique moment in Jerusalem’s history. Anyone interested in Jerusalem during the 19th and early 20th centuries will find this book of value.

Scholars debate the date that the Lower Aqueduct was built, but it is most commonly associated with the Hasmoneans. Clay pipes seen at various points along the route of the Lower Aqueduct illustrate its use into the 20th century.

This issue is also addressed in Matthew Teller’s recent book Nine Quarters of Jerusalem.

For a fascinating study of this quarter which uses GIS to map the Ottoman census, see this recent article by Michelle Campos.

Similar themes appear in Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine by Michelle Campos. Turning to earlier periods of the city’s history, John Hosler, who wrote a recent major study of medieval Jerusalem, concludes that the common focus on the city as a place of conflict is overstated. Listen to an interview about his book here.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous editions of this newsletter or follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.