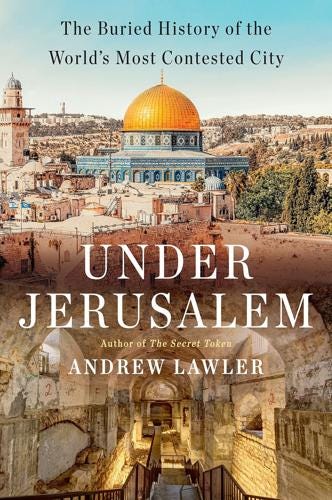

Summary and Review: Under Jerusalem, The Buried History of the World's Most Contested City by Andrew Lawler

Lawler's book shows how archaeology has affected the landscape of a contested city. The detailed narrative is a fun and engaging read but assumes the framing it claims to critique.

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

Under Jerusalem

Andrew Lawler’s highly touted book1 Under Jerusalem is an engaging and accessible account of select excavations in Jerusalem from the 1860s to the present day. The work is broken into three parts: part one focuses on early exploration of Jerusalem from the 1860s through 1967 when the Israelis captured East Jerusalem; part two covers the years 1967-2001 when peace talks collapsed; and part three extends from 2001 to today. Maps of Jerusalem at the beginning of each chapter highlight the location of key discussion points in the pages following.

Lawler’s narrative chronicles how the exploration of Jerusalem’s underground has had powerful effects on the city above. He contends that archaeologists who dig in the city have some responsibility to mitigate the ideological intents of their donors and wield influence over the way their excavations will inevitably affect changes in the city’s landscape. He even believes that archaeology is powerful enough to pave a path to peace.

Readers will benefit from Under Jerusalem in several ways. The book contains detailed narratives about more obscure (at least to me) archaeological ventures in Jerusalem such as Ron Wyatt’s search for the ark of the covenant on the grounds of the Garden Tomb, a two-decade lawsuit between a group of Coptic priests and an Arab shop owner into whose basement they burrowed (with the unofficial help of the IAA), Yehuda Getz’s attempt to break through Warren’s Gate and into the Noble Sanctuary’s underground, and others. Particularly interesting were the chapters that discussed the political ramifications of opening a new exit from the Western Wall Tunnels onto the Via Dolorosa. Even the well-known stories Lawler recounts are loaded with tantalizing details, many connected with the broader context in which the excavations occurred.

The book also includes material from Lawler’s personal interviews with archaeologists and locals, some of whom share information which may be unfamiliar to the reader. One of the most scandalous revelations in the book comes from Lawler’s interview with Meir Ben-Dov who relays that Yigal Yadin advised him to bulldoze the Umayyad palaces he had uncovered south of the Noble Sanctuary rather than reveal them to the public (144, 146). Thankfully Ben-Dov did not indulge Yadin.

Another strength of the book is that it gives a glimpse into the thorny context relating to archaeology in Jerusalem, especially in the chapters focused from the 1970s onward. Readers will learn how in general the religious-secular divide in Israel has contributed to very different orientations toward archeology in each community (especially in his discussion of Yigal Shiloh’s excavations on the Southeastern Hill). Lawler also discusses the historical reasons for different attitudes toward archaeology among Israelis and Palestinians. Additionally, the book highlights key players in Jerusalem, both individuals and organizations, and discusses them in relationship to each other, such as the IAA, Elad, the Western Wall Heritage Foundation, the Waqf, the Ecole Biblique, various ecclesiastical communities and educational institutions, invested politicians, donors, and others. Although it is by no means exhaustive, the web of information Lawler paints helps to bring some clarity to the knotty context in which Jerusalem’s excavations occur.

The cast of characters

The book follows a familiar cast of archaeological characters, but readers are not presented with a full-orbed account of Jerusalem’s excavation history. The excavations omitted from Lawler’s book are notable, including Hermann Guthe’s soundings on the Southeastern Hill, Broshi’s major digs across several areas on the Western Hill, Amiran and Eitan’s-and later Geva’s—work in the Citadel, Crowfoot and Fitzgerald’s dig on the Southeastern Hill, Hamilton’s excavations during the British Mandate, and Sukenik and Mayer’s excavation at the Third Wall, to mention a few. Other excavations are mentioned but hardly discussed, such as those of Johns, Avigad, Barkay, Kenyon, Gibson, Re'em, and others. The book also does not consider the many hundreds of routine and small-scale salvage digs that have taken place in Jerusalem.

Under Jerusalem focuses instead on the city’s most notorious, controversial, and ideologically driven excavations (probably in most cases better termed “digging activity”). More well-known figures in Jerusalem’s excavation history are one-dimensionalized to fit the narrative of the book: Edward Robinson is a “devout and conservative scholar” who used “the tools of science to counter religious skepticism” (xxxi); Charles Warren is a Freemason with “closely guarded spiritual reasons” for excavating in Jerusalem (40); Flinders-Petrie is “self-taught” (85); Vincent is an academic opportunist (111; see also 349); Kenyon is a “pious Anglican” searching for the City of David (130). This framing reflects Lawler’s view that Jerusalem’s archaeologists are best understood as biblical apologists or treasure-hunters (xxxi).

The book makes much of the fact that Vincent published a scientific report detailing the controversial and bizarre Parker Expedition. Lawler implies that Vincent did so for financial gain and in the process “turned a blind eye” to the chaos caused by Parker's nocturnal escapades on the Noble Sanctuary “for the sake of immediate scientific gain” (111). It is interesting that Lawler does not apply the same standard to his own book which happily makes use of the Parker Expedition to support its own narrative.

The excavations of Kathleen Kenyon, taking place over seven seasons and the most extensive the city had ever seen, are afforded only one page in the book. Here is part of the section:

“Confident that she could use this [new trenching] approach to find the still-missing City of David, she set to work with a team of Silwan workers on the slopes of the ridge extending south of the Noble Sanctuary. Jerusalem’s subterranean scramble, however, frustrated even the savvy Kenyon. Like Parker and Vincent, she found plenty of walls and fortifications dating to the millennium before the Israelite arrival. But Kenyon uncovered nothing clearly tied to the days of David and Solomon” (130).

The length of the section given to Kenyon reflects a common approach that minimizes her role in the excavation history of Jerusalem. Strangely, it also presents her as a kind of biblical apologist. As is well known, Kenyon had just come from Jericho where she refuted Garstang's popular claim to have uncovered the wall of Joshua. In a similar way, her excavations in Jerusalem demonstrated that the structures Macalister had unearthed on the Southeastern Hill and dated to the time of the Jebusites and King David in fact came from the Hellenistic Period—about a thousand years later.

Kenyon brought her rigorous archaeological method to Jerusalem and inaugurated a new era of scientific excavations in the city, the significance of which is not emphasized in the book. Her team excavated throughout East Jerusalem and pursued a variety of research goals related to several different historical periods. While some of her conclusions about Jerusalem’s history were controversial and later proved incorrect, Kenyon was no fundamentalist or treasure hunter as the book paints her.

Echoing the past

Under Jerusalem discusses how the city’s earliest excavations in the 19th and early 20th centuries created disputes between western archaeologists and locals. This foundation allows for later callbacks that connect controversial archaeological activity after 1967 to these early predecessors. For instance, when Yehuda Getz attempted to tunnel through Warren’s Gate under the Noble Sanctuary and was met by an group of appalled Muslim men, Lawler writes: “Palestinian Muslims suspected Getz had the quiet backing of the Israeli government, much as the Ottoman regime was implicated in the 1911 desecration (172; emphasis mine).” The desecration he refers to was Montagu Parker’s illicit digging on top of the Noble Sanctuary mentioned above. There are several such instances in the book connecting digging activity in Jerusalem after 1967 to earlier excavations, some loosely and others more tightly (e.g. 235, 296).

This framing is important for the book since it aims to draw a similarity between the early imperial archaeologists and later Israeli excavators. However, the attempt to mark a solid line from one to the other is not very compelling. Taking the above example, although Parker’s dig had massive political ramifications, one does not need to understand that context in order to grasp why Getz’s probe into the side of the Noble Sanctuary caused a huge controversy. We should also not imagine that knowledge of Parker’s 1911 dig on top of the platform hung around in the ether of Jerusalem (as implied on pg. 189) and somehow informed the response of the Waqf to Getz in 1981. Understanding the dynamics of the city and the fact that the Noble Sanctuary is sacred space provides enough context.

Misleading information and imagined controversies

The book is dotted with some misleading information. For example, Lawler repeats the idea that Charles Warren believed the shaft he climbed up in 1867 “must be the passage mentioned in the Bible that King David’s soldiers used to infiltrate and conquer Jebusite Jerusalem” (46; see also 87 and 210). In fact, it is not clear that Warren believed the shaft he discovered was the sinnor mentioned in II Samuel 5. The mistaken idea was only overtly applied to Warren’s Shaft later and not by Warren.2

In another place, Lawler writes that the Greek inscription discovered by Charles Clermont-Ganneau warning gentiles from passing beyond the stone balustrade and approaching the temple is “one of the few undisputed pieces of physical evidence from within the complex renovated under Herod the Great and destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE” (70). This is a strange statement considering that more than 500 pieces originating from the Royal Stoa built on the southern side of the Herodian Temple Mount and described in detail by Josephus have been recovered and published.3

Concerning the Nea Church uncovered in Nachman Avigad’s excavations, Lawler writes:

“…a church in the midst of the Jewish Quarter was anathema to many Orthodox Jews, and its vaults and apses were later locked behind gates and doors inaccessible to the public” (158; emphasis mine).

His overall point about the Nea Church is well-taken, namely that it is purposefully neglected. Even the informed visitor to the city will have difficulty in locating it, and it is near impossible to gain access to the key that unlocks the church vaults. However, the southern apse is hardly locked away. It sits in broad daylight visible to anyone willing to look for it. Apparently Lawler has not or was willing to exaggerate the point anyway.

Lawler also contends that rather than dig from the top down as is common practice, Ronny Reich and Eli Shukron opted to revive the old tunneling method of 19th-century archaeologists in their excavations near Jerusalem’s spring (211). While true enough that part of their excavations took place within ancient rock-cut tunnels, in all other places they employed the usual top-down excavation technique.

Under Jerusalem also presents some imagined controversies that stoke the fire of its narrative. From the time of Charles Warren, Lawler argues that there was a controversy of competing theories over the location of the City of David (70, 86, 88). Warren is said to be looking for the City of David in his excavations (46). However, the far and away majority view at the time still placed the City of David on the Western Hill (as Lawler mentions later). Despite some earlier suggestive breadcrumbs, it was not until closer to 1900—after the excavations of Bliss and Dickie—that the Southeastern Hill of Jerusalem came to be accepted as the ancient core. Lawler mentions this archaeological revolution but still uses an anachronistic controversy to hype Warren’s digs.

In an other instance he mentions the “…nagging question of the temples’ location, hotly debated among biblical scholars since Robinson’s day” (190; see also 258ff.). I would like to know what biblical scholars he has in mind. The overwhelming majority view in scholarship has been that all iterations of the temple building proper stood over the limestone bedrock under the Dome of the Rock. It is true that this remains a hypothetical conjecture, but there is a large amount of supporting evidence, especially geographical. The other scholarly views that I am aware of shift the temple’s location only a bit to the west (an older view that makes the Foundation Stone the location of the altar of burnt offerings) or to the north (near the Dome of the Spirits, setting the temple in line with the Golden Gate).4

There are more of these kinds of issues in the text. While any one of them is not a major problem by itself, together they obscure a number of facts in order the smooth the book’s narrative. Knowing the background to these problems, I find myself less confident in accepting other information in the book that relates to events with which I am less familiar.

Perpetuating old ideas

Lawler importantly mentions that Jerusalem’s four-quarter system is the synthetic creation of western outsiders (22, 353-354). However, readers of the book are still presented with a city marked by conflict:

“Ever since Abraham Lincoln was in the White House, when a French explorer broke into an ancient Jewish tomb, [Jerusalem’s] subterranean realm has sparked riots, threatened to trigger regional war, and set the entire world on edge” (xxvii).

This conflict is not just regional or between western archaeologist and city residents. Lawler writes that during De Saulcy’s expedition to the Tomb of the Kings in 1863, the governor of Jerusalem’s primary task was “to keep the peace in a city split among its three main religious communities, and in particular to maintain comity among the unruly Christian sects” (10). More of these kinds of statements appear in other places.5 An atmosphere of perpetual conflict in Jerusalem is the assumption underlying the book’s discussion of 19th and early-20th century digs, as well as those after 1967.

Western narratives that describe the city as a filthy and neglected place are presented as the impetus for the visitors to look underground for the “real” Jerusalem instead (xxxii-xxxiii). But the fact that Jerusalem was filthy and neglected or riddled in conflict is not questioned in the book.

These stereotypes of Late Ottoman Jerusalem were built mainly on the assumption that the writings of western visitors to the city should be taken at face value.6 Over the last several decades, scholars have pointed instead to Jerusalem’s rapid modernization in the second half of the 19th century and early 20th century which included a number of innovations.7 They have also suggested that the divisions wrought by the conflict of World War I and later British Mandate policies were much less pronounced in the earlier period Lawler writes about.

Lawler mentions the common disappointment of westerner travelers who arrived in Jerusalem. The city they encountered—most coming from some of the world’s largest urban centers at the heart of expanding global empires—did not meet their imagined expectations. However, the book does not discuss to what degree their observations about Jerusalem (such as Warren's or Mark Twain's) can be used as a fair window into the reality of the city they experienced. Native sources, such as the memoirs of Wasif Jawhariyyeh, paint Jerusalem in an entirely different light.

Conclusion

Lawler joins a host of authors who have written linear narratives about Jerusalem’s excavation history. Partway through the book I found myself wondering what its contribution would be. Considering that it focuses so heavily on the controversy created by archaeology in Jerusalem, I was surprised to read that Lawler believes archaeology could also serve as the seed for future peace. His rationale for this is not only because Jerusalem’s underground attests to the long presence of all three monotheistic religions but also because the archaeological process has revealed surprises that upended exclusive understandings of the city’s history.

The notorious Pontius Pilate was recently credited with building a massive street leading to the Herodian temple; elaborate Umayyad palaces near the Noble Sanctuary suggest a significant investment in Jerusalem beyond religious concerns very early in Islam’s history; the lack of monumental remains from the tenth century BCE has raised questions about how to understand the kingdoms of David and Solomon.

Lawler hopes that readers will accept his interpretation of the archaeological material, much of which is informed by minimalist views and tropes about the Bible, and set aside their differences. I suspect that those who are deeply invested in Jerusalem will not find this approach compelling.

Under Jerusalem is an engaging and page-turning read with important chapters, sources, and data points. But in the end, the book cannot escape from the same point of view that it claims to critique. Its fixation on the spectacle of archaeological stories throughout is summarized in its final words asserting that Jerusalem’s “abiding power remains bound up in its underworld” (344). I agree with Michael Press that this view attributes too much potency to the city’s subterranean realm. It also echoes the same framework of Jerusalem’s early explorers who looked past the living city in efforts to find the real and powerful one hidden below.

Few who are paying attention will question Lawler’s assertion that archaeology has become a tool of control in a contested city. Readers will have to judge how well this book can serve as a guide to this and other issues related to Jerusalem’s archaeological past.

Pages 22-24, 74-75, 221.

Demonstrated for instance in the writings of scholars like Yehoshua Ben-Arieh.

See for example the writings of Vincent Lemire, Yair Wallach, Michelle Campos, Roberto Mazza, and Salim Tamari.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous editions of this newsletter or follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.

Great review! Agree about enjoying the sections of the book that were new info to me, and appreciate your critique of his overall emphasis.

Side question - did Kenyon’s car emerge in the recent parking lot project?