Did Hezekiah Tear Down Houses to Fortify Jerusalem's Wall?

A popular interpretation connects preparations for war in Isaiah 22:10 with a fortification wall uncovered in the Jewish Quarter. Is it legitimate?

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription and receive unique Jerusalem-related benefits.

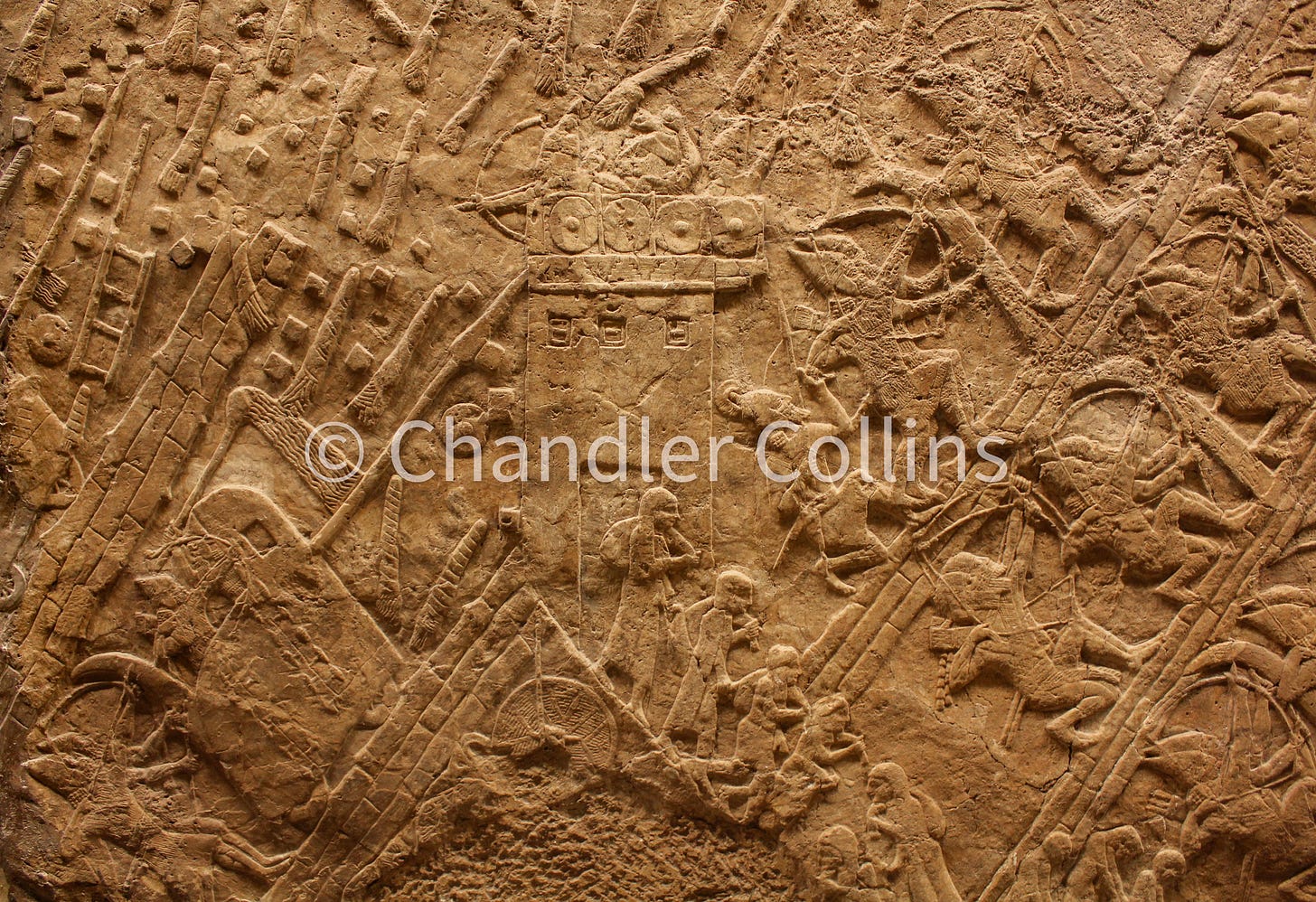

In 1970, the foundational courses of a massive fortification wall from the time of the Judahite monarchy (Iron Age II) was uncovered during the reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter. A portion of the now-famous wall has been preserved in an open-air display for residents and tourists. Nahman Avigad, who directed the salvage excavations in which it was found, deemed it the “Broad Wall” after a wall mentioned in Nehemiah 3:8 (I prefer to call it “Avigad’s Wall” instead and will do so here).

Today’s post explores some earlier remains that were uncovered at the foot of Avigad’s Wall along much of its trajectory. The wall ran over or “cut” them, destroying these buildings. Avigad believed the large fortification wall was built by King Hezekiah as part of his preparations for Assyrian attack by Sennacherib’s army in 701 BCE (II Kings 18-19). He associated the large wall and destroyed buildings at its base with the description of wartime activities in Isaiah 22:10: “You counted the houses of Jerusalem, and you broke down the houses to fortify the wall (NRSV).”

Avigad began publishing this interpretation at least as early as the 1980s. It appeared in Discovering Jerusalem, his popular book describing the Jewish Quarter excavations:

“That the quarter on the Western Hill was undefended in its earliest stage is clearly shown by the fact that our wall was built partly over the ruins of earlier Israelite houses. Those houses were disregarded in selecting the line of defence, and were demolished where necessary to make way for the wall. Indeed Isaiah actually describes the emergency measures adopted in the face of approaching danger, in preparation for war: "...and you saw that the breaches of the city of David were many, and you collected the waters of the lower pool, and you counted the houses of Jerusalem, and you broke down the houses to fortify the wall.” (1983:134; original emphasis)

Writing elsewhere about the connection between these archaeological finds and Isaiah 22:10, Avigad called the wall and destroyed buildings at its foot “visual evidence of this very passage” (1985:471). This interpretation was followed by Hillel Geva who published the final report on Area A where the wall was found (2003:192).

Though Avigad’s Wall is not as popular as other sites in Jerusalem, tour groups are regularly brought there and given an explanation of its historical setting, including Avigad’s understanding of Isaiah 22:10 (I have done this myself many times). This interpretation seems to be virtually unchallenged in scholarly literature, finding affirmation in archaeological histories (A. Mazar 1990:420), commentaries on Isaiah (Blenkinsopp 2000:334), guidebooks (Murphy-O’Connor 2008:76), and histories of Jerusalem (Auld and Steiner 1996:40). This is a great example of an interpretation of Jerusalem’s biblical history that emerged as a result of largescale excavations in the 1970s and 1980s that became both well-disseminated in the tourism circuit and integrated in scholarly literature.1

Perhaps it exists somewhere (if so, please point me to it), but I have never seen a close examination of both the biblical text and archaeological context in order to evaluate the plausibility of Avigad’s claim. The goal of this post is to take a first step toward doing this. Is it legitimate to connect the wartime activities described in Is. 22:10 with the wall and destroyed buildings uncovered in 1970, as Avigad did? On what assumptions does this interpretation depend? Let’s examine a few basic considerations.

Archaeological ambiguity

Avigad’s Wall runs over many features that preexisted it in Area A, but the most significant is a building known as Structure 363. Part of Structure 363 can still be seen today, though it has recently become obscured by walkways that were installed for a new exhibit at the site. The function of this large casemate-like building is unknown. As far as I know, there are only two possibilities for its identity.

First, it may have been part of a casemate wall that surrounded either (1) an unknown local feature, or (2) perhaps all or part of the Western Hill prior to the building of Avigad’s Wall. The final excavation report discusses this possibility but ultimately rejects it (Geva (ed) 2003:509). However, if Structure 363 was a casemate wall, it follows that Avigad’s Wall was simply built along a similar trajectory when it succeeded the old one. It would be a stretch, then, to associate a fortification wall with “houses” (בתים) mentioned in an ancient text.

In the final excavation report, Structure 363 is identified instead as a fortified farmstead (Geva (ed) 2003:509). This is not a “house” in the strict sense of the word used in Is. 22:10, although the Hebrew term is more elastic and can be applied to buildings of many kinds and sizes. Avigad nonetheless described Structure 363 as a “house,” which fit with his interpretation of Is. 22:10. Additional unrelated wall fragments uncovered nearby were also disrupted by the construction of Avigad’s Wall. They may represent remains of houses, but this is not clear. Although the term “house” is very flexible, we should better understand the intended function of these fragmentary building remains before we seek to connect them with structures mentioned in an ancient text. With a better understanding of their function, we can then ask if it would be appropriate for Is. 22:10 to characterize them as “houses” (בתים).

In Avigad’s imminent-domain style interpretation, houses that sat along the trajectory of the wall were expropriated in order to make way for the new fortification wall. Its construction was needed quickly due to the immediate threat of the Assyrian army. This understanding implies that “living” structures were dismantled in short order because they sat along a topographically strategic line of defense.

However, it is not clear if any of the buildings demolished by Avigad’s Wall were still in use at the time it was constructed. In fact, some earlier features in Area A are known to have been covered by dirt fill and debris before Avigad’s Wall was built. Therefore, it is possible that Structure 363 and the other wall fragments that were cut by the construction of Avigad’s Wall were actually not “living” buildings when the wall was built. On this understanding, these structures would simply have fallen into disuse and perhaps disrepair. If this was the case, it is difficult to see why such buildings would be worthy of comment in the biblical material.

The dating of Avigad’s Wall is another important factor. Due to historical considerations, most scholars accept that Avigad’s Wall was built at the end of the 8th century BCE by Hezekiah, the same view Avigad pioneered. However, the archaeological data is not that specific and allows for a range of at least several decades in either direction.

A new radiocarbon study has suggested that Jerusalem’s major fortifications, built in the 8th century BCE and usually assigned to the time of Hezekiah (apparently including Avigad’s Wall), should be bumped several decades earlier in time and attributed instead to his great grandfather Uzziah (Regev et al 2024:8). I believe this study’s conclusions about the Western Hill are problematic for reasons I outline here, but this interpretation is nonetheless possible. Other scholars such as Meir Ben-Dov and Diana Edelman (2011:59-60) had already attributed Avigad’s Wall to Uzziah for other reasons.

Although less likely, some scholars even date Avigad’s Wall to Manasseh who reigned after Hezekiah (Guillaume 2008:198-199). Avigad initially considered this possibility but later rejected it (1970:133). Understanding the date of the wall is obviously an essential piece of determining whether or not it can be connected with “the wall” of Is. 22:10b.

Textual complications

Turning now to the biblical text, Isaiah 22 contains some interpretive difficulties. The first is narrowing its context. This chapter, which contains a judgement against the people of Jerusalem, describes an unnamed wartime setting. Verse 10, our verse of interest, mentions the tearing down of buildings in order to fortify Jerusalem’s wall. This was apparently related to preparation for the unnamed war, and, as many commentators have pointed out, language in verses 8b-11 seems too specific to be simply a literary invention.

Because Isaiah 22 does not name the war in question, scholars have connected it with several different historical events. The majority view is definitely the same one Avgiad adopted, that it relates to Sennacherib’s campaign in 701 BCE. However, there are other options, including Sargon II’s campaign in 711 BCE. Some scholars even relate it to one of the later Babylonian campaigns against Jerusalem under Nebuchadnezzar, or they at least read verses 8b-11 as having been reshaped by a writer who lived during that time. Other historical settings may also be possible. Whatever option we may prefer, there is language in the chapter that seems to be an outlier and demands some explanation. Even if we assume (with the majority of commentators) that Is. 22:10 relates to preparations for Sennacherib’s campaign in 701 BCE, we should recognize that we are taking an interpretive step beyond what is clear in the text.

The grammar of verse 10 also raises some interpretive difficulties: “You counted the houses of Jerusalem, and you broke down the houses to fortify the wall (NRSV).” The “you” in this verse is often associated with Hezekiah, although he is not mentioned in the chapter. It is also important to note that, despite the appearance in English, the “you” in vs. 10 is plural (“y’all”) rather than singular (as in the rest of vss. 9-11). In the immediate context, the crowds celebrating at the beginning of the chapter may be in view. It remains to be understood if and how the grammar of this verse might be related to the person of Hezekiah.

We may also ask what it means to “count houses,” and if the counting of houses in vs. 10a was an activity separate from or related to the houses being torn down in vs. 10b. Commentators guess variously that houses were counted in order to determine (1) the available space for refugees who fled to Jerusalem during the war, (2) which buildings could afford to be torn down or had fallen into disrepair and so could be used for material to build the wall (if so, why number them?), or (3) something else. I have not seen Avigad address what “counting houses” means or if/how this activity was a necessary prerequisite to tearing them down.

A third issue has to do with the verb “to fortify” (לבצר). The form we encounter in this verse (piel stem) only occurs twice in the Hebrew Bible. Though often translated “to fortify,” its most basic meaning seems to be “to make inaccessible” (HALOT I.148) This understanding fits well with the other place it occurs (Jer. 51:53). The verb may imply the wholesale construction of a new wall, as Avigad thought, but there are several other possible meanings. Here are a few that I have encountered:

strengthening breaches in a preexisting wall (Stacey 2018:134)

adding to the thickness of a preexisting wall (my suggestion)

filling in the gap of a casemate wall (Oswalt 1986:413)

removing structures on or near the wall order to improve line of sight for Judahite defenders (Wildberger 1997:369)

removing structures built outside the city wall to make it less accessible for an enemy army (Childs 2001:156)

Some of these understandings would be difficult or impossible to detect archaeologically. Any attempt to connect Is. 22:10 with material remains must address the ambiguity of this verb.

One final interpretive difficulty derives from Isaiah 22 but is also geographical. Verses 8b-11 mention several other built features in Jerusalem: the Forest House (vs. 8), City of David (vs. 9a), the lower pool (vs. 9b), and the reservoir between the two walls for the old pool (vs. 11a). Even if scholars debate the specific location of each item in the list, they generally assume that they were situated somewhere along Jerusalem’s eastern ridgeline. Although it is not impossible, reference to a fortification project on the Western Hill in vs. 8b seems disconnected from the logic of the list. This understanding fits the general pattern we see across the Hebrew Bible, where the settlement on Jerusalem’s Western Hill goes almost entirely unmentioned.

Keeping our options open

In summary, for Avigad’s theory about Isaiah 22:10 to be convincing, we would need to have a high degree of confidence about the following:

the date of Avigad’s Wall

the function of the destroyed buildings at the foot of Avigad’s Wall

the date of the destroyed buildings relative to Avigad’s Wall

whether these buildings could fairly be considered referents of the Hebrew term בתים (“houses”)

the identity of the unnamed war in Is. 22

if and how later editing may have reshaped vs. 10 in light of other events

whether the verb “to fortify” refers to the wholesale building of a new wall over other possible meanings, along with the other grammatical issues in vs. 10

whether verse 10b intended to refer to building activities on the Western Hill in a list of items built on the eastern ridgeline

There are a lot of moving pieces here that are glossed over by appeal to an archaeological interpretation. The tangibility of material remains can tempt us to simplify a complex problem. To my mind, there is nothing that seems to discount the possibility of Avigad’s interpretation. Much of his work to integrate text and archaeology in Jerusalem was ingenious and pioneering, based on freshly uncovered material. It all merits engagement, which is what I am attempting to do here. However, the level of confidence often associated with his interpretation of Isaiah 22:10 seems definitely premature. Until more data emerges, it is best to consider the idea put forward by Avigad as one of several legitimate possibilities and to reserve judgment on a conclusive interpretation.

Another popular one concerns a wave of northern refugees that settled on Jerusalem’s Western Hill and increased the city’s size exponentially in just a few years.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee. Less than 1% of readers do this, and it makes an enormous difference.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View the newsletter archive and follow Approaching Jerusalem on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.

Hey Chandler, I really appreciate you taking a deeper look at the "Broad Wall" theory. I was doing some study on Nehemiah a while back and kept coming across wall and gate references and wondering, "How certain are we of this identification?" - including the broad wall references. Thanks for a great job examining the available evidence!

The mention of and Hilkiah strengthen a Hezekiah/Ahaz time for Isaiah 22.