Jerusalem in Brief (No. 10)

The Ordnance Survey Map of 1865, Kathleen Kenyon's view of ancient Jerusalem, and a new book by Lukas Landmann

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription and receive unique Jerusalem-related benefits.

Jerusalem visualized

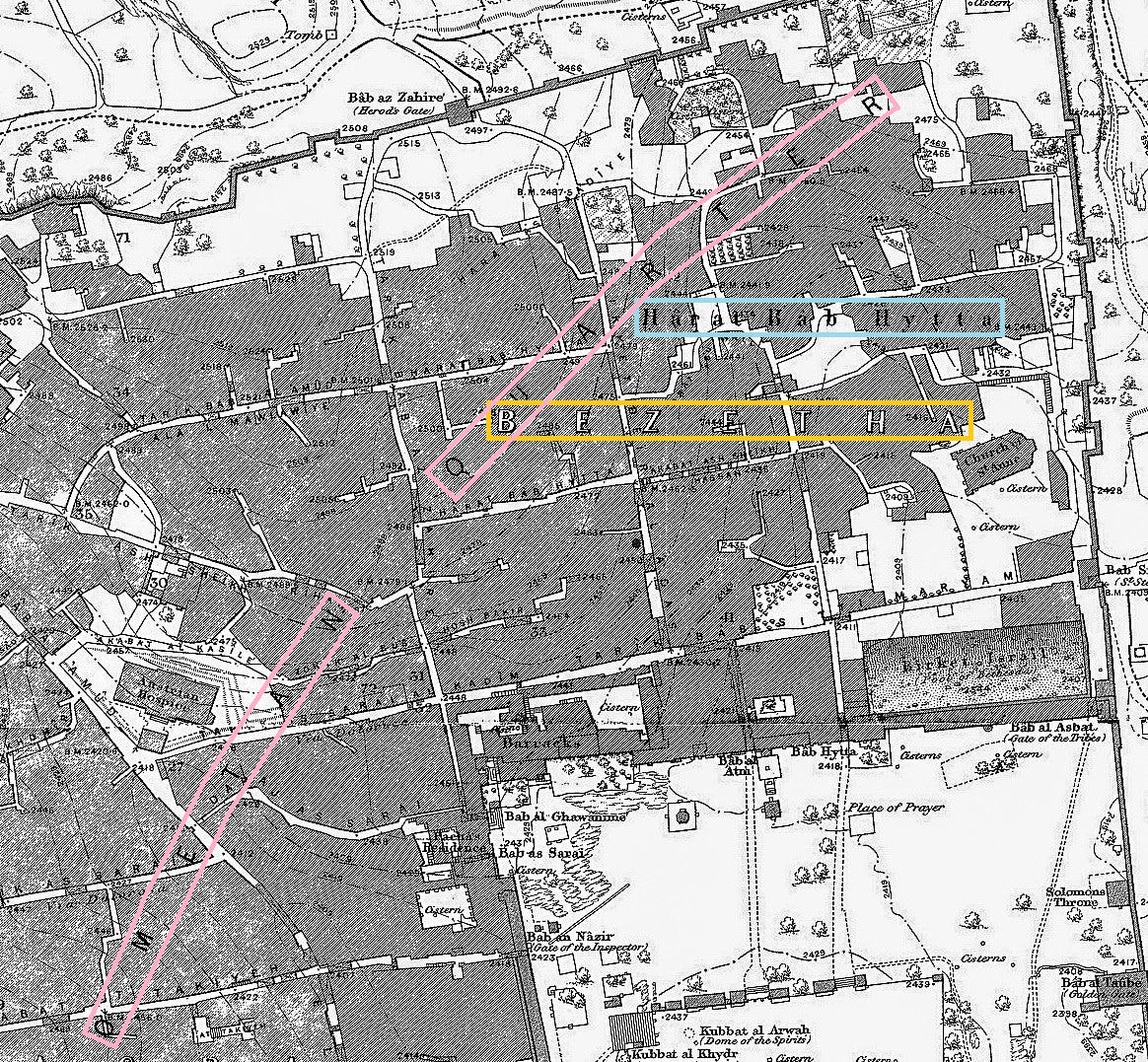

Above is a clipping of a map that was produced by British Royal Engineers during the 1865 Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem (for some background, see here). The Ordnance Survey map is a wonder for its attempt to meticulously measure the walled city and its immediate environs. With its publication, accurate elevation levels were included on a map of Jerusalem for the first time. It is still practically useful in navigating the Old City today, even though some areas have obviously been updated in small ways since its publication. Others have been more significantly altered, like the historic Jewish Quarter which was near totally reconstructed in the decades following 1967.1 Though the modern architecture and new features we encounter there today bear limited resemblance to the Late Ottoman Period, the Ordnance Survey map can still help reveal some spaces where old masonry stands or the former blueprint was retained.

The Ordnance Survey map depicts a city composed of grey building blocks and surrounded by a fortification wall marked by a thin outline. White streets cut and weave through these blocks like a mycelial network through leaf litter on a forest floor. Some blank areas inside the city indicate public spaces, gardens, or otherwise unutilized locations. The exterior terrain is largely undeveloped but marked into plots that were used for annual and perennial agriculture.

Some built features stand out against the homogeneous grey blocks that fill the city. The unique shape of the Citadel, located in the center of the western fortification line, is emphasized against the more lightly shaded moat surrounding it. It also contains an individual monument labeled “David’s Tower.” The Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque (center right) naturally stand out against a white background, as do the smaller Austrian Hospice (center) and Church of Saint Anne (top right). By contrast, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (center right), which, by logic of the map, should have been absorbed into the grey mass, was deliberately outlined and more darkly shaded. The Hurva and Tiferet Yisrael Synagogues are thinly outlined, whereas other buildings like the Church of Saint James or Greek Orthodox Patriarchate are subsumed into the ubiquitous grey and marked only by a number pointing to the map key. One wonders at the factors that influenced these and other similar decisions.

The neighborhood-level toponyms reveal some interesting things about the cartographer’s point of view. Jerusalem’s supposed four quarters are marked in block letters that sweep from southwest to northeast, showing how widely accepted this non-native imposition had become by the mid-1860s (more on that here). Within those quarters, three smaller neighborhoods are also marked: Ḥârat Bâb as Silsilé (center right), Ḥârat Bâb al ʾAmûd (top center), and Ḥârat Bâb Ḥyṭṭa (top right). Many other locally derived quarter names were omitted. The decision to include these is somewhat surprising, given that they complicate the integrity of the quadripartite system.

Some ancient toponyms were also included. Such labels are often found on maps from the mid-19th century and reflect broad enthusiasm associated with Jerusalem’s ancient topography during this period. Three place names from the writings of Josephus are written latitudinally in white block letters: Bezetha (top right), Acra (center), and Zion (bottom left). The inclusion of these ancient toponyms both reveals topographical theories of the time and emphasizes the deeply seeded interest in the city of the past, even for engineers carrying out precise and objective mapwork.

Notes & Quotes

Most readers will be familiar with an old debate about the size of ancient Jerusalem which is usually referred to as the Minimalist-Maximalist Controversy. This debate took place mainly during the 1950s-1960s (with roots stretching back earlier) when it dominated scholarly literature about Jerusalem in the time of the Judahite Monarchy (Iron Age II).

The vast majority of scholars, who were termed “Minimalists,” believed that Jerusalem remained small during this time. It was restricted to the city’s Eastern Ridge, which is equal to today’s Noble Sanctuary/Temple Mount and Wadi Hilweh. The Maximalist position was represented by a small group of scholars who held that the ancient city had become much larger. They believed that it had grown onto the Western Ridge, which includes the modern Armenian and Jewish Quarters along with Mount Zion and its eastern slopes (for a slightly longer explanation of this debate, see here).

In the end, excavations on the Western Hill proved that most scholars had been incorrect, when unexpected evidence of a settlement and fortification walls were uncovered from the time of the Judahite Monarchy. Scholars now needed to integrate this evidence and reconsider their understanding of Jerusalem during this period.

Like nearly all scholars, British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon had been a proponent of the Minimalist position. She excavated in Jerusalem from 1961-1967 and believed that her results strongly supported it. After later excavations proved the Minimalist understanding incorrect, she modified her view slightly and chose to accept that only a small portion of the Western Hill had been included in the ancient walled city. The area she added is equivalent to the modern Jewish Quarter and part of the adjacent Central Valley (1974:146). She continued to maintain adamantly that Jerusalem’s ancient fortification wall could not have included either the slopes of modern Mount Zion, the lower parts of the Central Valley, or the Pool of Siloam. These aspects of her views are frequently mentioned in literature summarizing her work.

However, I did not know until recently that, while retaining some conclusions mentioned above, she also came to accept the possibility that the western line of the fortifications could have extended much further west than she originally thought, to the area near the Armenian Garden. Below I present an excerpt from a letter written by Kenyon to the editor of Israel Exploration Journal in 1975, which, as far as I know, was her last published comment on the size of ancient Jerusalem before she passed away in 1978:

“I would see no objection to [the] suggested line approaching more nearly to the Armenian Garden; we neither of us, of course, have any evidence at present. But I do remain very firm that the extension cannot continue round to enclose the Pool of Siloam, for the fact that we did not find Iron Age II occupation on the western hill cannot be put down to the small area excavated. My plan shows that in fact we did excavate an area that was cumulatively large, and the evidence from all sites was absolutely negative. The individual sites on the eastern slope of the western hill were mostly small, but they are numerous and well spaced out. The sites on the western slope of the eastern hill, K, N, M, were all large and were carried down to rock (O and W were unfinished). So, though I am ready to accept any variation of a wall enclosing the northern end of the summit of the western ridge, I remain adamant on the southern end.” (1975:192)

Recent arrivals

I recently received my copy of Jerusalem: Faces of a City by Lukas Landmann which was published last year. This thick hardcover work doubles well as a coffee table or reference book. It contains extensive high-quality photos. The book begins with a short introduction to the topography of Jerusalem and then follows the story of the city chronologically, starting in the earliest periods. Each chapter includes a map illustrating the fortifications and some architecture in the city during that period. A final chapter addresses “Shifting Views on Sacred Sites.”

The accompanying text is written in English, Arabic, and Hebrew. This linguistic gesture toward the communities of Jerusalem is commendable but feels a bit superfluous, as it seems doubtful whether they will constitute the book’s primary readership. Moreover, because the organizing language is English, readers of the Semitic languages are required to flip the pages backward from left to right in order to follow the text. Landmann recognizes and comments on this issue (10). Without the additional Hebrew and Arabic text, the book could either have been much smaller or included more of the excellent photos.

The standout feature in this work is undoubtedly its photography, which was almost entirely captured by the author. Landmann’s impressive photo library includes images of museums, artifacts, landscapes, and communities of Jerusalem. As someone who spent years traversing the city with camera in hand, I can tell that he has invested an enormous effort in the photography for this book. His photos show deliberately unique angles on familiar landmarks, painstakingly detailed shots, and crisp images from environments with low light. The book also includes some photos of rare sites, such as the Armenian Birds Mosaic north of Damascus Gate (108-109) and the ship drawing in the bowels of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (98). The chapters on Late Ottoman and Mandate Jerusalem contain an extensive photo catalog of buildings constructed in the 19th and 20th centuries as the city grew outside its walls.

This book will surely serve a function in my reference library for its vast and varied interaction with sites across Jerusalem and in many different historical periods. Having spent limited time reading the text, it is difficult to know how helpful it will be. Sources are not cited in the entries, but a bibliography of 27 items is listed in the back. After a preliminary reading, the book’s contribution seems to be the impressive site documentation and photography. This body of photos warrants deep appreciation for Landmann’s effort to show Jerusalem in fresh and captivating ways.

Paid Supporters

The next livestream is scheduled for March 11 from 8:00-9:30pm ET. Paid supporters will receive a private link beforehand.

During these events, I discuss excavations, publications, pop media articles, and developments relevant to historical Jerusalem. I also share resources and occasionally present original research. Participants will have the opportunity to ask questions. Paid subscribers get access these quarterly events and the archive of previous recordings.

The nearby Mughrabi Quarter was also forcibly depopulated, demolished, and subsumed into the Jewish Quarter as the Western Wall Plaza of today.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee. Less than 1% of readers do this, and it makes an enormous difference.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View the newsletter archive and follow Approaching Jerusalem on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.