The Scarping of Jerusalem

Monumental construction projects reshaped Jerusalem's terrain by cutting vertical bedrock scarps. This post explores four examples.

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription and receive unique Jerusalem-related benefits.

Learning the fundamentals of Jerusalem’s topography is an essential part of doing historical research on the city. One aspect of this subject that I find fascinating is how pieces of the geography were altered artificially and later became subsumed into the shape of the city. The historical origins of these changes were lost, and the new physical form of Jerusalem that emerged was taken for granted in later periods. Archaeology and source material can help reveal some details of these historical processes.

I have written elsewhere about the flattening of Jerusalem’s terrain, where I discussed large-scale horizontal spaces that were created during monumental construction projects and their continued influence on the city’s topography today. This post will look at some of the major vertical rock scarps that were artificially hewn in antiquity both inside and outside the city wall. More examples of this phenomenon can be found in other posts, such as the bedrock that is visible at the northwestern corner of the Noble Sanctuary.

The Cardo Maximus

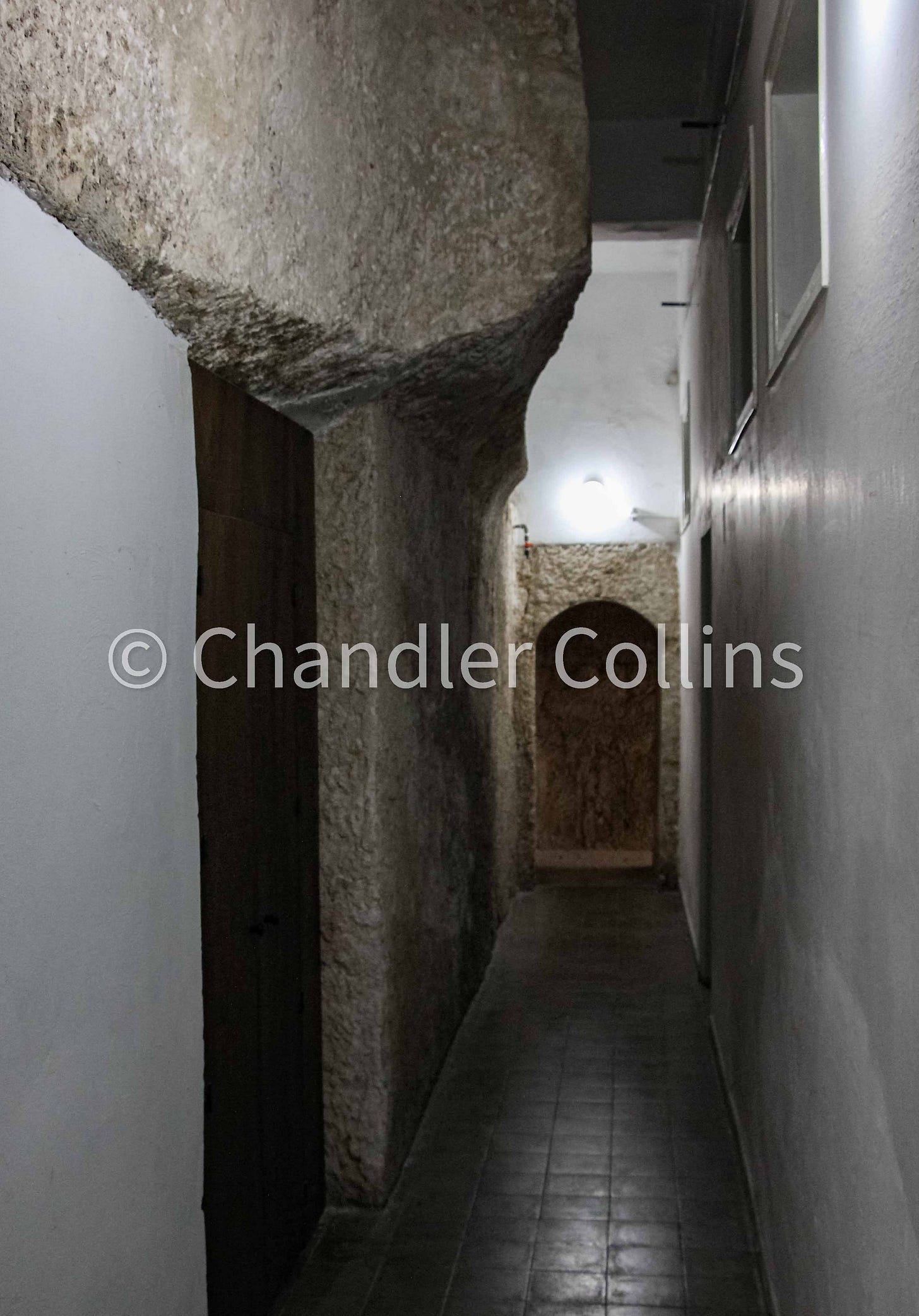

Our first vertical scarp can be found in the modern Jewish Quarter where the Cardo Maximus was laid during the Byzantine Period. The southern extension of this north-south street was built as a way to provide access to the monumental Nea Church that was sponsored by Emperor Justinian. At one point near the southern part of today’s Jewish Quarter Road, the builders encountered a bedrock saddle that descends from the modern Armenian Quarter on the west. Their solution was to shave part of the bedrock away in order to lay the street at an even level in this area (Gutfeld 2012). This created a vertical scarp into which shops were built.

Interestingly, a high bedrock level was also revealed in excavations on the opposite side of the Cardo below and near the Hurva Synagogue. This demonstrates that a vertical scarp also existed at the eastern edge of the street. So, in effect, the Byzantine builders cut a rock trench here into which the Cardo was laid. However, only the western half of it can be seen today. Several centuries later, the street went out of use and began to be filled in. It was revealed after 1967 during the reconstruction and expansion of the Ottoman-era Jewish Quarter.

The Eastern Cardo

Another limestone scarp can be found at the western edge of today’s Western Wall Plaza, the former location of the Mughrabi Quarter. Visitors who access the plaza by either of its two western entrances will notice the rapid descent via streets and staircases that follow the natural slopes of Western Hill and then drop vertically over the scarp to the plaza below.

The shape of this natural scarp was altered artificially in antiquity. Excavations in the plaza uncovered part of Jerusalem’s Eastern (or secondary) Cardo and demonstrated that its builders shaved a section of bedrock in this area as part of its construction. Unlike the portion of the Cardo Maximus highlighted above, which was partially constructed within a rock trench, this area of the eastern Cardo abutted a high vertical cliff on its west and was open to the lower slopes on the east. Some evidence of quarrying during the time of the Judahite Monarchy (Iron Age II) was also found in the excavations, indicating that this scarp probably began to be shaped during that time.

The Northern Old City Wall

Several artificial rock scarps are visible along Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent Street just north of the Old City. The largest stretch of vertical limestone is found at the foot of the Ottoman wall between Damascus and Herod’s Gate. Another scarp stands prominently opposite the wall on the north. It once contained features reminiscent of a skull face and became known as Gordon’s Calvary during the 1890s. Jeremiah’s Grotto is located along the same scarp on the east, with the Garden Tomb to the west.

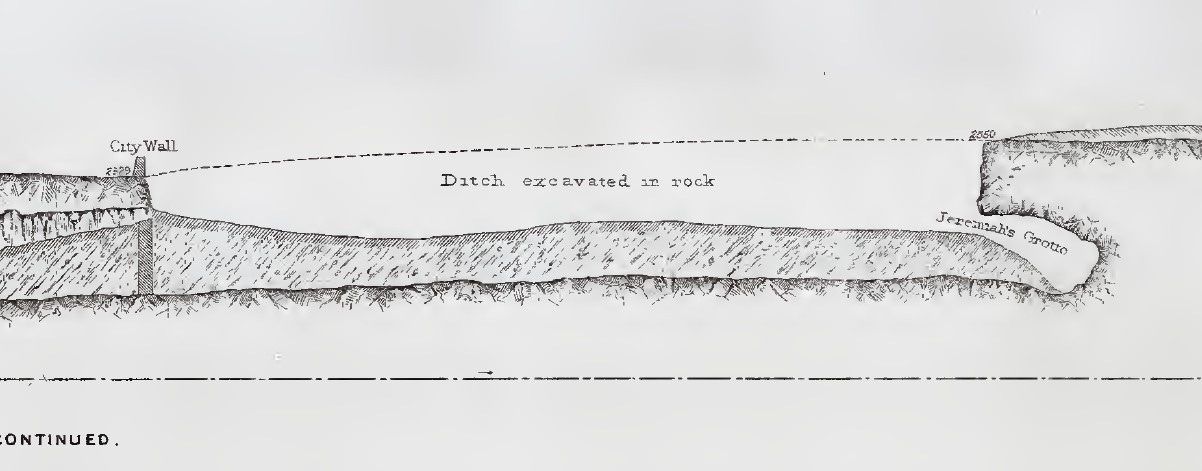

The obvious remains of a trench between the northeastern corner of the Old City wall and the Rockefeller/Palestine Archaeological Museum shows that an artificial moat was cut along the northern edge of Jerusalem to protect what has always historically been the city’s most vulnerable side. This fact was observed already in the 19th century by scholars like Edward Robinson (1841:345), George Williams (1845:283n2), and Charles Warren (see below).

At least some of the trenching in this area seems to have been formed by quarrying activity, which in some cases may date back to the time of the Judahite Monarchy/Iron Age II (Barkay 1997). Other parts were deepened and expanded during the medieval period (Weksler-Bdolah in Galor and Avni (eds) 2011:424). A well-known a defensive moat surrounded Jerusalem prior to the First Crusade, parts of which were recently uncovered recently in this area.

Maudslay’s Scarp

The final scarp in our survey is located at the southwestern edge of modern Mount Zion where the hill forms a natural corner that turns toward the east. In this area, the edge of Mount Zion was artificially hewn to create the foundations for Jerusalem’s fortification wall. This took place either in the Early Hellenistic/Hasmonean Period or perhaps earlier during the time of the Judahite Monarchy (Iron Age II). The original Bishop Gobat School building, today the home of Jerusalem University College, was constructed upon this scarp in 1853.

In 1874, the Englishman Henry Maudslay uncovered significant portions of the scarp for some length during repairs to the school. It was named “Maudslay’s Scarp” after him, though this term is not well-known today. The vertical scarp is visible in several places on JUC’s campus. Another portion, along with a rock-cut staircase, can be seen in the Protestant Cemetery to the east.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee. Less than 1% of readers do this, and it makes an enormous difference.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View the newsletter archive and follow Approaching Jerusalem on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.

Fascinating research. I am curious about the equipment used and the possible recycling of rock. Thank you.