Flattening Jerusalem's Terrain in Antiquity

Artificial platforms of massive proportions altered Jerusalem's landscape while also destroying or concealing remains of former times. This article briefly explores four examples.

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

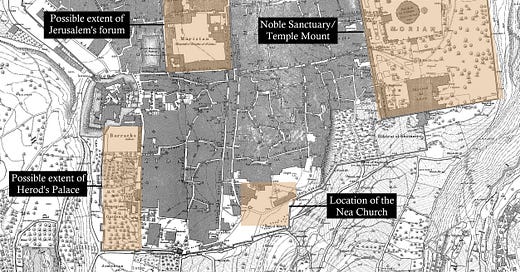

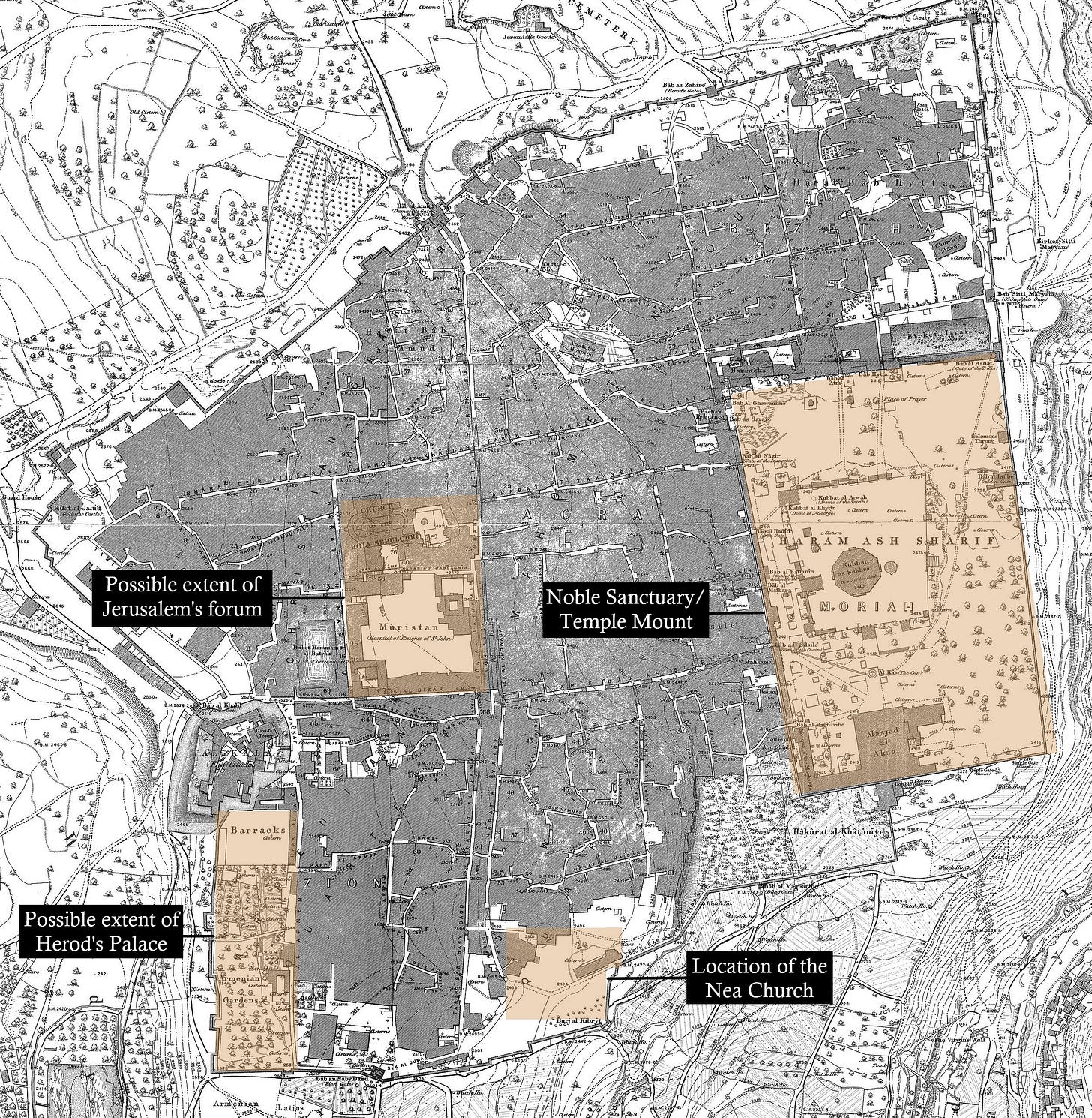

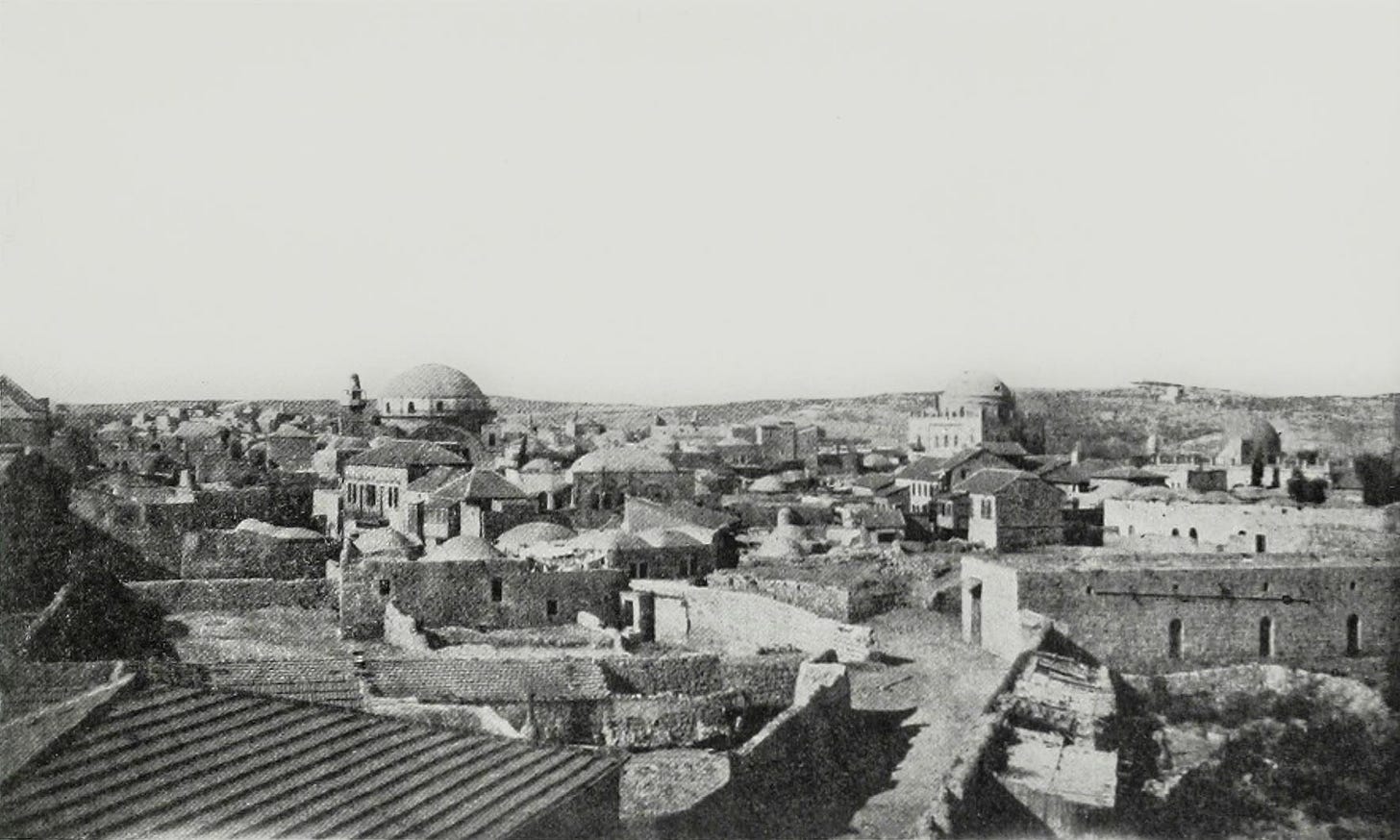

Anyone who travels by foot in Jerusalem develops a more tangible connection to their lungs. The dips and ascents in the city’s landscape are unavoidable, even for its most knowledgeable residents. Patches of level terrain, whether a long street or crest of a hill, are both a welcome reprieve and an exception to the city’s geographical rule. In some of these cases, city streets were simply paved along limited naturally level spaces in Jerusalem. In others, the terrain was intentionally shaped by the ancients who bent the landscape of Jerusalem toward their purposes. This post highlights four examples of artificially level areas in Jerusalem that were created in antiquity but continue to influence the city we experience today.

One Artificial Platform to Rule Them All

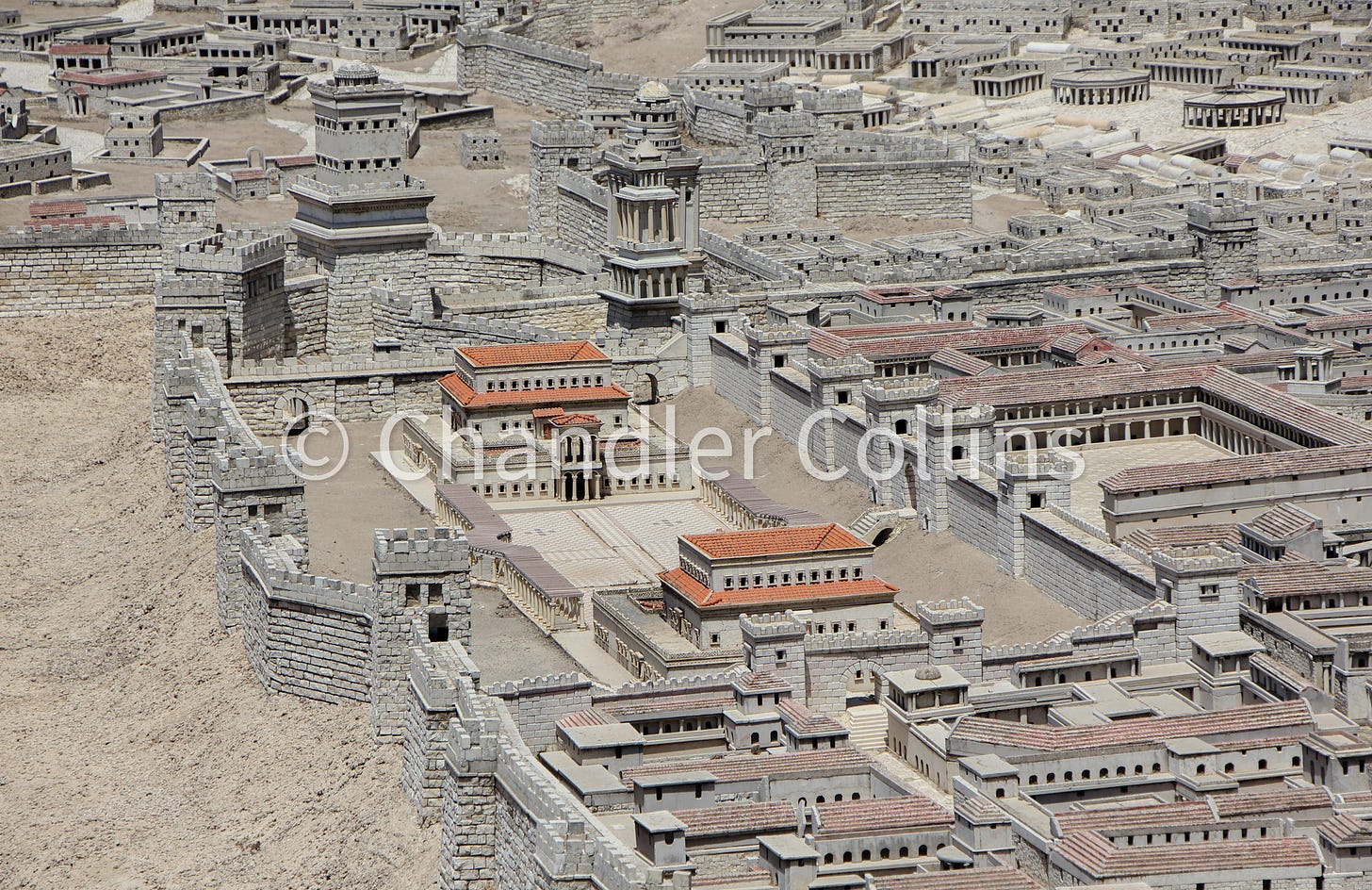

Let’s begin with the obvious. The Noble Sanctuary (al-Haram al-Sharif), which was also the location of the ancient Jewish and Judahite temples, is the most striking example of an artificial platform in Jerusalem. With more than 50% of its total retaining walls visible today, it can be appreciated from nearly all vantage points in the city but especially from the Mount of Olives.

Based on the available evidence, most scholars assume that the foundational courses for Herod’s Temple Mount1 at least doubled the size of the preexisting temple area. This project also seriously altered the shape of Jerusalem before his time. It enveloped the Mountain itself within the new ca. 35-acre enclosure and nearly eviscerated two nearby valley systems. The southern extension of the platform, in which Robinson’s Arch is embedded, consists of a series of artificial vaults that supported the buildings on top. In this way, Herod obscured the contours of Jerusalem’s topography and concealed preexisting parts of the city while also creating a new space for Jewish worship and public gathering.

A Western Palace

Herod the Great’s palace complex was built upon a large podium that was founded on the height of the Western Hill. This created a kind of symmetry in Jerusalem’s landscape with two large artificial platforms standing out on the city’s eastern and western ridges. Very little, if anything, remains from Herod’s palace, but evidence of a massive amount of fill material and subterranean retaining walls have been uncovered by archaeologists along the inside of the Old City walls south of Jaffa Gate. An impressive rampart of debris was also excavated outside the Old City walls (See here on pg. 152). This supported Herod’s palace on the west side and prevented it from collapsing into the Hinnom Valley (wadi er-Rababa) below. The information from these excavations and ancient written sources leads most historians of Jerusalem to believe the western end of Herod’s palace stretched from near the Tower of David to the southern Old City walls of today.

The modern impact of Herod’s ancient project can be felt in the terrain of the southwestern corner of the Old City and along Armenian Patriarchate Street. Observant frequenters of these areas will notice that they are strikingly level and that the landscape begins to descend toward the modern Jewish Quarter just east of Armenian Patriarchate Street. This is one place in Jerusalem where monumental efforts of the past, though totally invisible today, still shape our experience as we traverse the Old City.

The Nea Church

Just inside Zion Gate and a bit downslope is a parking lot that sits just south of the Hurva Synagogue. Buried beneath the parking lot and the adjacent buildings is a massive Byzantine Church that was once the biggest in Jerusalem. The New Church of the Holy Mother of God and Ever-Virgin Mary—more commonly known as the Nea Church—was constructed in the 6th century CE during the reign of the Emperor Justinian. Although the existence of the church was always widely known from ancient texts and more recently from the Madaba Map, its exact location was debated (some in the 19th century even thought it had been built in the spot of the al-Aqsa Mosque).

In one of the many Israeli excavations that took place in Jerusalem in the years following 1967, pieces of the Nea Church were uncovered, including an inscription that cemented its identification. The church seems to have been built largely on bedrock that was cleared of most earlier debris. But at least some of its southern buildings, and perhaps even part of the church itself, rest on massive subterranean vaults that were also used as cisterns. In Justinian’s day, this church anchored the southern part of the Upper City along the main north-south street (Cardo Maximus) which was also uncovered nearby. The Emperor’s project not only leveled the terrain in this area but extended an artificial shelf over the hillside to the south in a way that has continued to impact the city’s topography. These efforts to flatten the terrain can still be appreciated while walking in the parking lot mentioned above or along the street leading down to Dung Gate (Bab al-Maghariba).

Hadrian’s (and Constantine’s) Forum

Our last artificial platform sits in an area known as the Muristan, in the heart of the modern Christian Quarter and just south of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Information from excavations and written sources suggests that this space served as a quarry and perhaps a garden of some type until it was built up in the second century CE.

According to most archaeologists and historians, Emperor Hadrian reshaped the area and leveled it to create the city’s forum when he reestablished Jerusalem as a Roman city (Aelia Capitolina). As with the other above projects, workers would have needed to cover the area with a large amount of fill material to create a level terrain upon which they could establish the new forum. A Roman temple, and later the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, was built in the northern portion of this space. Although scholars debate the exact size of the forum, excavations in the area show that it existed. The artificial fill obscured the preexisting quarry and continue to give shape to the level streets in the Muristan even today.

Artificial Terrain as Part of Jerusalem’s Geography

This brief look at artificial platforms in Jerusalem shows that they became a common feature in the city’s geography, impacting something like one-fourth of the area inside the Old City walls. These four projects (and others) that artificially altered the topography of Jerusalem are important no matter what period of Jerusalem’s history might interest us. To study historical Jerusalem involves both appreciating the city’s natural geography, as well as understanding the ways it was altered over time and how those changes affected future engagement with the city.

Looking a little more closely at just one of the above examples, Herod’s mammoth expansion of the Temple Mount platform must be accounted for when studying Jerusalem’s history both after and before Herod. Early Muslim architects did not start with a blank slate. They were forced to reckon with the preexisting structure of Herod’s project when they established their new sacred enclosure and nearby palaces in the 7th century CE. The foundational retaining wall courses served as the outline for the Noble Sanctuary. The artificial fill and vaulted structures became the foundation for monumental buildings that enshrined new meanings on Jerusalem’s landscape.

Likewise, the impact of Herod’s Temple Mount must also be applied backwards toward an understanding of earlier periods. Historians who are interested in Jerusalem before Herod must recognize the effects of his project on the city’s architecture and landscape. As we mentioned above, Herod not only concealed most of the sacred Mountain itself, along with whatever earlier enclosure stood there, but also buried two of Jerusalem’s valley systems under tons of debris. Without being able to physically remove Herod’s project or undo its impact, scholars must propose earlier reconstructions of Jerusalem as best they can by using all the tools at their disposal. Understanding the Temple Mount before Herod may also offer new interpretations of Herod’s actions or elucidate the new meanings for his architecture on the Mount.

The original builders of these monumental artificial platforms were not the first to use these areas of Jerusalem or to infuse them with meaning, and they were not the last. Therefore, we should not prioritize the importance of their history over others who lived before or after them. Instead, the impact of these four projects of antiquity (and others) should be recognized and understood on their own terms, and then integrated into how we study and appreciate the complex history of Jerusalem.

Most scholars today recognize that the building of the Temple Mount took many years and almost certainly outlived Herod, as reflected in John 2:20 (for one example, see here). I use the term “Herodian Temple Mount” out of convenience.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous editions of this newsletter or follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.