The Staircase that Launched an Excavation for Jerusalem's Ancient Walls

A set of rock-cut steps once served as the inspiration to uncover the southwestern corner of Mount Zion. Today they are virtually unknown.

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

In a 2004 article that was a summary of his M.A. thesis at Jerusalem University College, Brian Schultz explored the archaeological heritage of the Protestant Cemetery on the southern slope of modern Mount Zion. This includes: a rock scarp that once held Jerusalem’s walls, tombs, Jewish ritual baths, (mikve’ot), inscriptions, and more. Schultz made the observation that among all these finds, it was the excitement around a rock-cut flight of steps discovered in the Protestant Cemetery that originally fueled the drive for other archaeological projects in this area. In this post, I want to explore the early conversation around this staircase that inspired at least nine excavations that have followed its discovery.

Finding A Staircase

The progression by which the rock-cut steps were initially uncovered is not entirely clear. What seems more certain is that they were first commented on in print by an Italian would-be architect, real estate broker, and explorer of Jerusalem named Ermete Pierotti. One day, probably in the late 1850s, his wanderings led him to an intriguing area along the southern end of Mount Zion in search of Jerusalem’s ancient walls. This space had a partially visible rock scarp that was littered with ancient remains. He observed:

"…I examined the part of Mount Sion which is outside the present wall, and found in the Protestant cemetery the vertical hewn rock, and a flight of steps close by cut out of it, which were discovered by the workmen employed by the Mission; at the same time large stones were also dug up in the ground, such as are frequently thrown out by the spades of the husbandmen.” (1864:23)

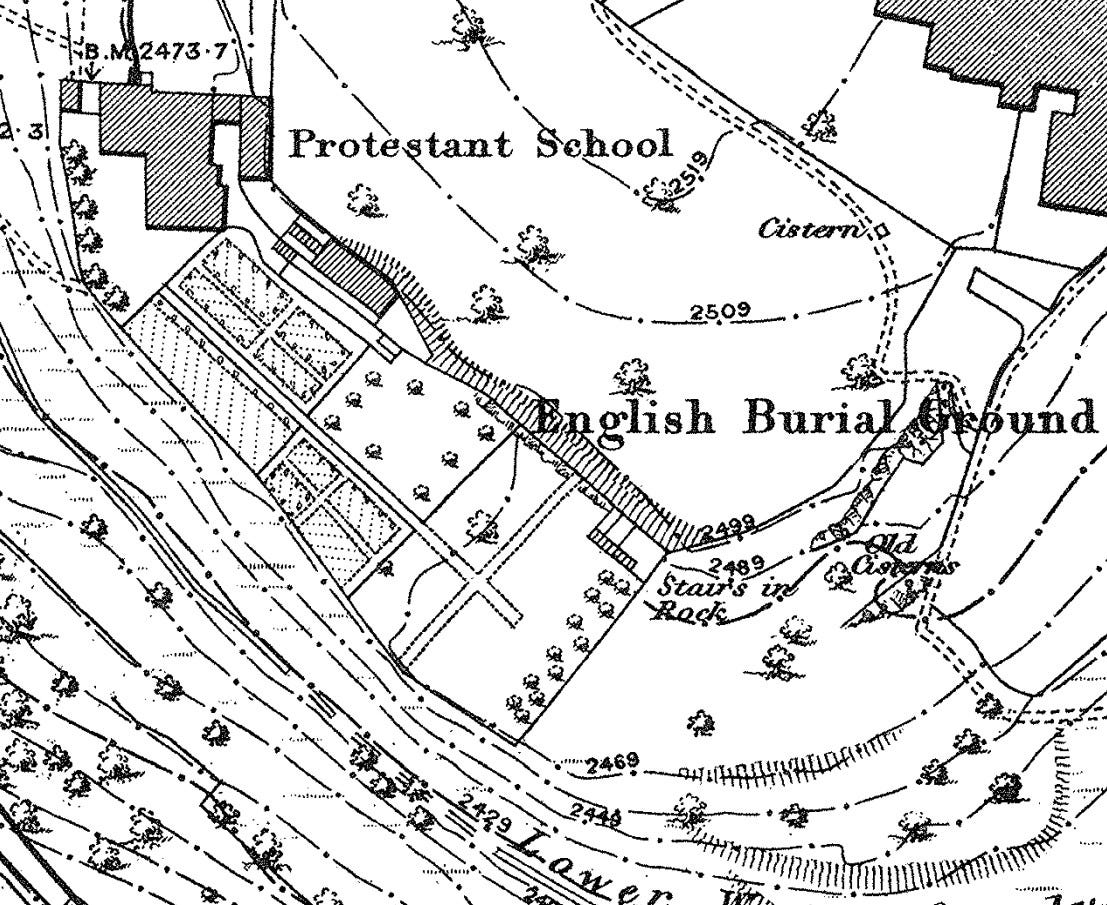

It seems that the flight of steps was already visible when Pierotti arrived in the cemetery. They probably first appeared when the ground was leveled to create the cemetery in 1848 (Warren and Wilson 1871:280). Later, Pierotti employed some workmen to dig around Mount Zion but does not appear to have uncovered any more of the stairs himself. However, he thought they were important enough to include on his map of Jerusalem published in 1864.

Following Pierotti, a string of Englishmen, most of them British Royal Engineers, became intrigued by the rock-cut staircase. During his time in Jerusalem carrying out the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem in 1865, Charles Wilson noticed them and commented in his survey report:

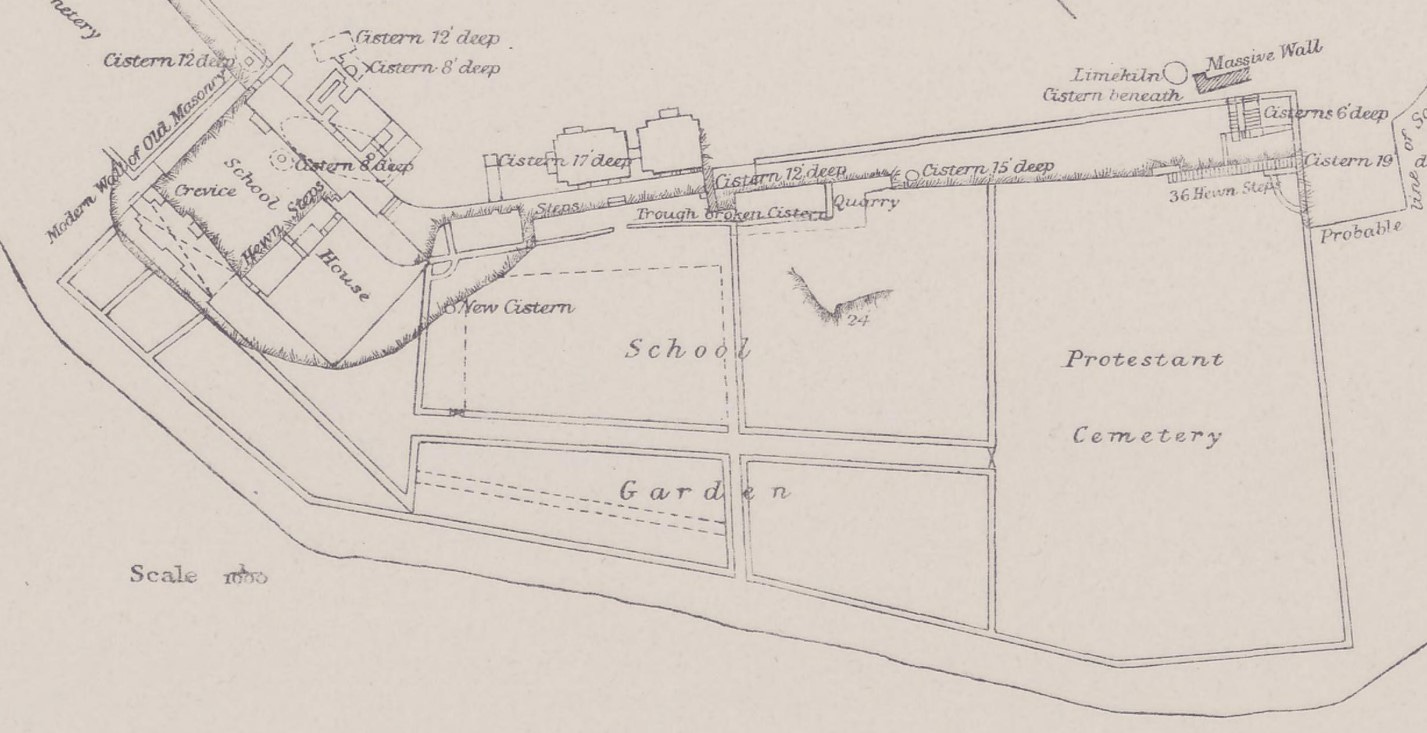

“From the Mission Schools [(the Gobat School)] to the end of the Protestant Cemetery an escarpment of the rock can be traced, which is best seen at the end of the cemetery, where there is a flight of steps hewn out of the rock. These have been traced downwards for some distance by excavations made by the Mission, but the loose rubbish has prevented their reaching the bottom.” (1865:61)

Intriguingly, in later writings, both Charles Warren (1876:158-159) and Claude Reignier Conder (1872:168)—Royal Engineers and colleagues of Wilson—credit him with having excavated these steps. This is strange, given that as we saw in the quote above, Wilson himself does not claim to have excavated the steps.1 We should add that Wilson systematically listed all the areas in Jerusalem where he excavated during his survey in 1865 (such as at the foot of Robinson’s Arch). The rock steps in the Protestant Cemetery are not mentioned in the list.

In any case, Wilson marked the stairs on his Ordnance Survey Map. They were also considered important enough for his team member James Macdonald to photograph them. The photo is important because it shows how deep the steps extend below the level of the cemetery.

Fast forward two years to 1867. The success of Wilson’s Ordnance Survey had inspired the launching of the Palestine Exploration Fund, and Charles Warren arrived in Jerusalem to excavate on its behalf. Warren is usually remembered for his digging activity on Jerusalem’s eastern ridgeline near the Noble Sanctuary. However, the rock-cut steps that had been observed by Pierotti and Wilson also led him to investigate this area of the Western Hill. Warren mentions uncovering a total of 36 steps, then arriving at a landing:

This was the continuation of the laying bare of some steps cut in the solid rock, discovered when the cemetery was levelled. The rock here appears to have formed part of the ancient wall of Zion…The excavation reached a depth of 18 feet, and on arriving at the thirty-sixth step a landing was found, and a gallery was driven along it for 17 feet without any results. This landing was probably the foot of the rock scarp, which must have presented to the enemy a perpendicular face of 29 feet in height." (Warren and Wilson 1871:280)

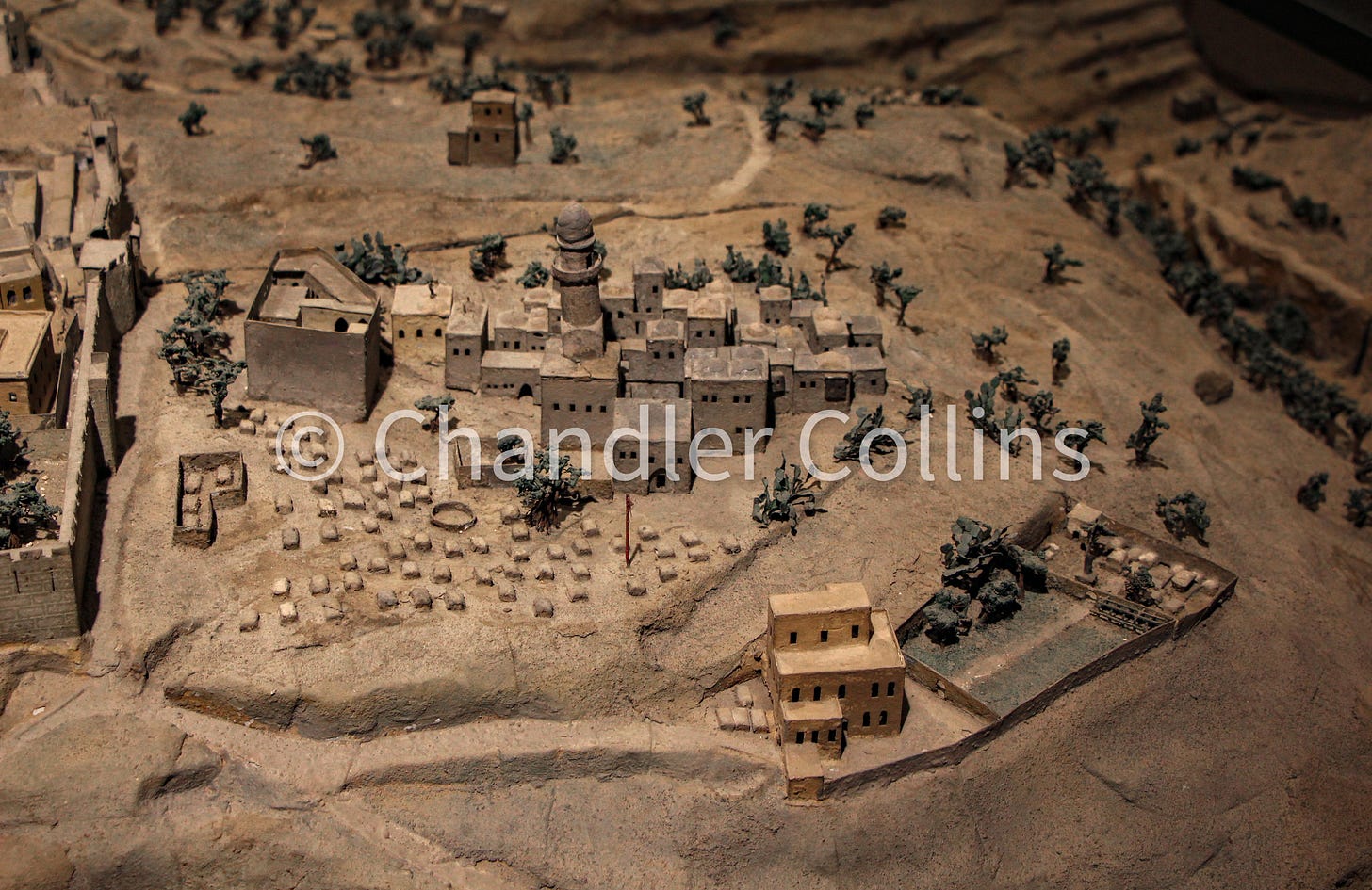

We might expect such a well-known excavation to be reflected in contemporary works about Jerusalem. In 1873, Stefan Illés completed an impressive relief map of Jerusalem which would later be shown at the World’s Fair. This treasure of Late Ottoman Jerusalem is displayed in the Tower of David Museum today but is unfortunately difficult to find due to its location in the basement. Among the many striking details on the map, Illés interestingly saw fit to include these rock-cut steps as they had been uncovered by Warren.

An Inspiration for the Future

Due mainly to the excitement around the steps, Warren and Conder both encouraged others to excavate on the southwestern corner of Mount Zion. Their call was answered in 1874 by Henry Maudslay, another member of the Palestine Exploration Fund, who uncovered the entire length of the bedrock scarp from the Gobat School to the end of the Protestant Cemetery. From 1894-1897, another excavation by Fredrick Jones Bliss and Archibald Dickie continued the work of Maudslay digging in the other direction. They tunneled along the ancient city wall down down to the Central Valley and, among other things, uncovered multiple city gates in the process. Other excavations have also taken place near the cemetery, including the ongoing work of the German Protestant Institute of Archaeology.

Very interestingly, in a recent salvage dig outside the school buildings, Amit Re’em uncovered some stairs just downslope from the entrance of the Jerusalem University College gate. In his publication of the dig, he wonders if his stairs were originally built as part of a long staircase that once brought foot traffic from the valley below to the top of Mount Zion. Those steps may have been connected with another set of rock-cut steps higher up the hill (further west than the ones discussed above). If a massive staircase running up the slope of the Western Hill existed here, it is also possible that our staircase of interest in the Protestant Cemetery once did the same.

Given the visible rock scarp along the southwestern slope of Mount Zion and the construction and expansion of the Bishop Gobat School, perhaps it was inevitable that this area would become the target of archaeologists. But more than any other feature on the landscape, the stone staircase in the Protestant Cemetery was a unique inspiration. Ironically, as excavations opened the area, new discoveries came to overshadow the steps which were eventually reburied. Today the staircase that once captured the attention of archaeologists and scholars of Jerusalem goes largely unnoticed by visitors in a quiet corner of the cemetery.

Afterward

Several weeks after publishing this article, I came across this photo taken by Auguste Salzmann in 1854. It shows the rock staircase with at least 19 steps uncovered. The date of the photo shows clearly that the stairs were uncovered well before Wilson or Pierotti came to Jerusalem. Probably neither of them excavated it, but it had been unearthed already when the Protestant Cemetery was first opened.

I am not sure what to make of this. The common denominator between Warren and Conder is that they do not mention Ermete Pierotti, who had already written about the steps, and that they credit Wilson with excavating them, something he seems never to have explicitly claimed to do. It is possible that Pierotti or Wilson did excavate the steps but that neither explicitly mention it. It is also possible that due to some scandals related to Pierotti, Warren and Conder preferred not to mention him or to credit his achievement to Wilson. More likely, the workers associated with the Gobat School and Anglican Mission to the Holy Land had progressively exposed a few more of the steps out of their own interests. Perhaps a dive into the archive at the Palestine Exploration Fund would clarify the matter.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous editions of this newsletter or follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.