William Bartlett's Lament over Mount Zion

What we can learn about Jerusalem from an excerpt of a 19th-century travelogue

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

In the summer of 1842, the British traveler and artist William Bartlett visited Jerusalem for the first time. He later published an account of his travels in the book Walks about the City and Environs of Jerusalem which also includes some of his sketches. Bartlett takes readers around the city on three walks and describes landmarks and people he encounters along the way. Despite its age, the book contains some valuable content that is still referenced by scholars working on the history of Jerusalem, such as a description of the excavations that laid the foundations for Christ Church just inside Jaffa Gate. Bartlett was a follower of Edward Robinson, and he defended most of Robinson’s interpretations of Jerusalem’s topography. At one point, he even featured in the debate between Robinson and George Williams. This post explores an excerpt from Bartlett’s book.

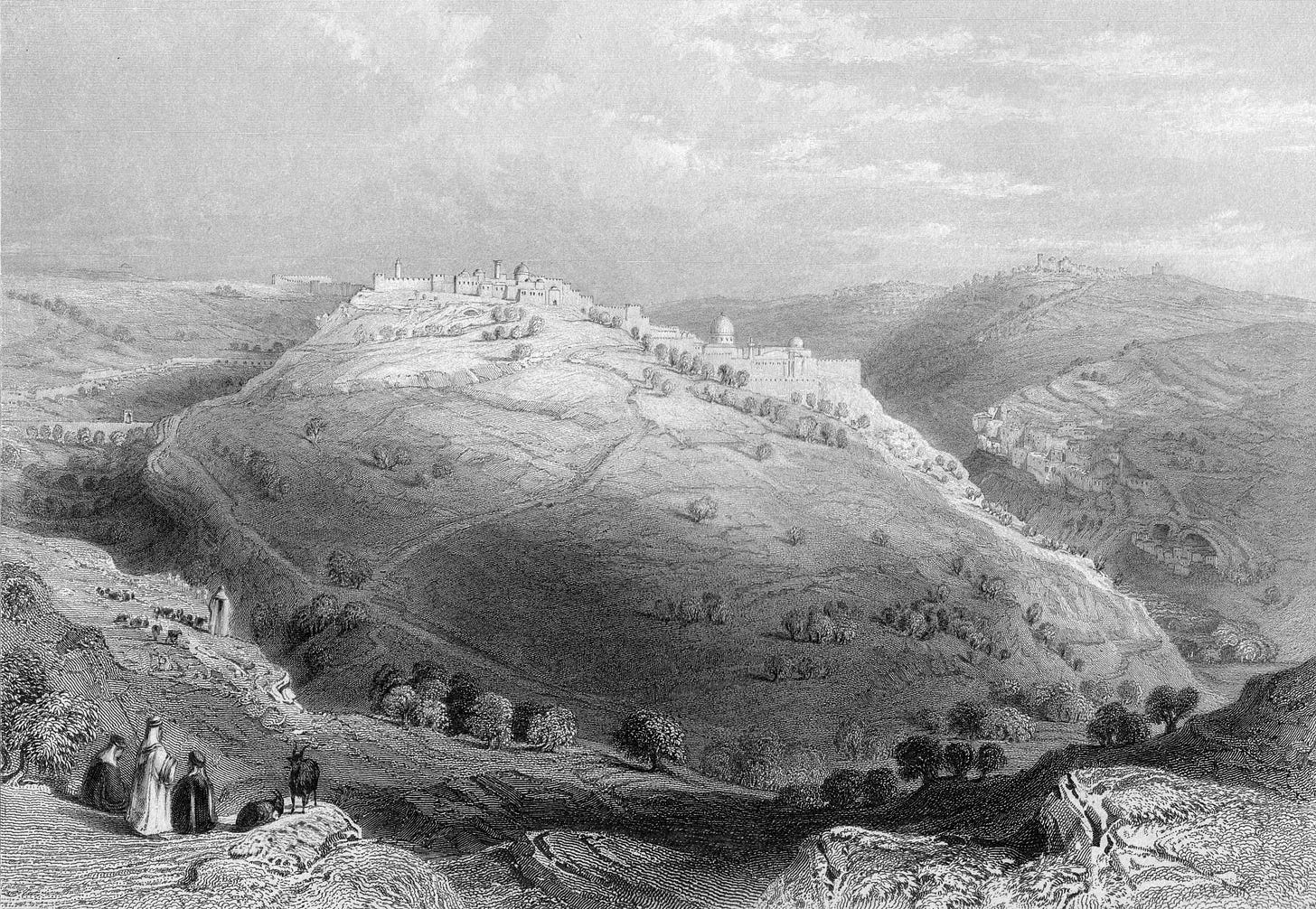

A view to Mount Zion

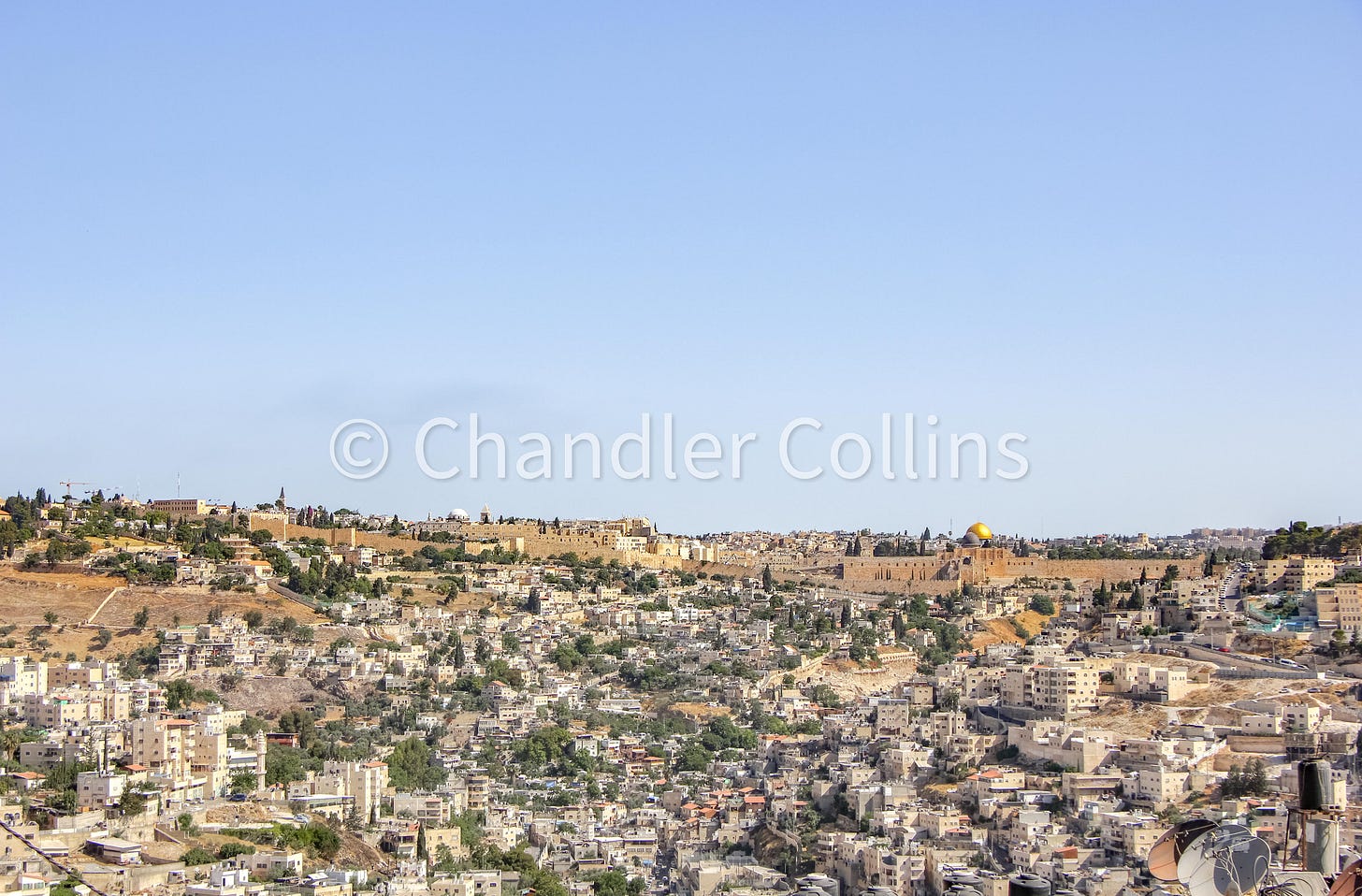

The first walk highlighted in the book brings him to the so-called Hill of Evil Counsel. By tradition, Judas met there with the Jerusalemite priestly leadership to negotiate a price for the betrayal of Jesus. From this vantage point located immediately south of Jerusalem’s historic basin, Bartlett faced the bare hill of Mount Zion, which sits outside the current line of the city walls.

Mount Zion is one geographical component of Jerusalem’s Western Hill. Its modern name should not be confused with the sacred Mount Zion of biblical literature where the Judahite and Jewish temples once stood. Regardless, in the mid-19th century when Bartlett visited the city, most scholars believed it to be the ancient core of Jerusalem and home to the Jebusite fortress of Zion and the City of David. Archaeological excavations over the last 150 years have shown this once-prevalent idea to be incorrect. However, understanding this view’s popularity in Bartlett’s day will help us better appreciate him. From his perch on the Hill of Evil Counsel, he lamented the modern fate of Mount Zion as he pondered its glorious past:

“…we shall have no difficulty in bringing before the mind's eye [Mount Zion’s] ancient condition. The fort of the Jebusites, the “upper city,” occupied the crest and level of the hill; the lower town probably extended nearly to its base, and a strong wall encircled the whole. In the time of David, its general appearance must have been the same, but with an increase in the number and beauty of the buildings. On the brow of the hill, a noble and commanding position, overlooking the rest of the city and the deep valleys and rugged mountains which stood round as bulwarks and defences, emblematic of the protection of Jehovah to his chosen people, stood the palace of the poet-king [David]…The scattered allusions to his favourite dwelling-place are still appropriately descriptive of its general position and character; but where is the splendour with which it was invested by his imagination? Who can see, in the bleak, unpicturesque hill before him, surrounded with gloomy ravines and arid and desolate ridges of naked rock, that Mount Zion, “beautiful in situation, the joy of the whole earth,” of which glorious things are said not only in the Psalms, but throughout the whole range of Hebrew poetry? Its dull slopes, once covered with towers and palaces, and thronged by a people whose bones are mingled with the soil, are now terraced and ploughed, and but sustain a poor crop of wheat and sprinkling of olive-trees. Broken paths descend into the valleys below; and a flock of goats, with a solitary shepherd, or at long intervals an Arab woman, slowly mounting the steep ascent, alone relieve the melancholy vacancy of a scene, which in general is silent as the grave.” (1844:59-61)

Thinking about Late Ottoman Jerusalem

The tone and vocabulary in this passage clearly portray Bartlett’s disappointment. They also accord with the assumption, present in other writings of 19th-century Christian travelers, that the Holy Land suffered under a divine curse initiated at the rejection of Jesus the Messiah. Some disturbing passages in this corpus of literature even apply the curse to the peoples of the land. Bartlett is not immune from this tendency throughout his book which exhibits serious prejudices against all sorts of Jerusalemites. In the above passage, his reflection on people is restricted to the final sentence where sad and lonely pedestrians traverse Mount Zion’s broken paths.

The better part of the excerpt is focused on the curse’s effect on the ground. For Bartlett, modern Mount Zion is “bleak” and “unpicturesque,” “surrounded with gloomy ravines and arid and desolate ridges of naked rock.” These themes are consistent with his earlier impressions of Jerusalem’s surrounding landscape as “dead…sad, stony, and sterile” (1844:14-15). Though he observes that southern Jerusalem was divided into agricultural plots, something corroborated by historical photographs, the passage nonetheless focuses the area’s sterility. The overall context suggests his interpretation is more informed by his theological preoccupations than an appreciation for Jerusalem’s landscape.

In evaluating the excerpt, it is helpful to know that Bartlett’s visit took place during the month of June. Most readers of this newsletter will know that the bulk of the seasonal rain in the Holy Land falls during December and January. The result is a thick green carpet of grass peppered with wildflowers that emerges usually in late January and runs through February, March, and some of April. By late April or May, heavy rains cease, and the low growth begins to die back, taking on the deceptive look of sterility until the rain begins again in the fall. Had he visited earlier in the year, he would not have found the landscape as amenable to his description.1

Yet evidence of fertility could have been detected by Bartlett even in June. Despite the brown look of the terrain in the Holy Land during the summer and fall months, important local produce begins to develop during this time. Barley and wheat are harvested in April and May, and summer fruits like grapes, pomegranates, figs—and the olives in Bartlett’s view—grow and ripen from late summer. Observing the presence of fruit developing on the trees, even well before harvest, is a reminder of the annual cycle’s endurance.

In another post looking at western travelogues from the 19th century, I cautioned against using their descriptions of Jerusalem as objective sources for understanding the city during this period. This idea (not at all original to me) is supported by texts like Bartlett’s. It also shows the dangers of characterizing the Holy Land on the basis of short-term stays where visitors are not exposed to the entire annual cycle.

Thinking about ancient Jerusalem

Bartlett’s lament also clarifies understandings of ancient Jerusalem during his own day. Though he looked over a bare hill with no architecture, its “noble and commanding position” engaged his imagination as he envisioned what the city might have been like during the time of the United Monarchy. For Bartlett, Psalm 48 (which he partially quotes) suggest that massive building projects once crowned the high and defensible Western Hill during the reign of David.2

As mentioned above, Bartlett’s acceptance of Mount Zion as the most ancient core of Jerusalem was not his innovation but the widely shared assumption of nearly all scholars of his day. Though it would later be proven incorrect, this view assigned ideological value to the Western Hill during the time of the Judahite monarchy (Iron Age II), something that has been lost today. This hill was an important place for Bartlett because it was home to the fortress of Zion and City of David. The conceptual significance of the Western Hill is clear in his disappointment over its supposed fallen state in 1842.

Future archaeological work would challenge the idea that the Western Hill had been an early or even important part of Jerusalem. In fact, several decades after Bartlett published his travelogue, scholarship on Jerusalem underwent a revolution, and most scholars came to accept that the Western Hill had not been founded as the ancient core of the city.3 By the 1950s and 1960s, nearly all doubted that it had been settled in any meaningful way during the time of the Judahite Monarchy.4 The once-glorious hill had fallen into obscurity.

Though today all scholars continue to hold that the Western Hill was not the historical core of the city, archaeological work on the hill has established that it was in fact fortified and included in the city of Jerusalem during the time of the Judahite kings. Regardless, the Western Hill holds no obvious conceptual or ideological value today as it once did for Bartlett. It tends to be discussed simply as an appendage to the core of the ancient city where the Temple Mount and royal quarter were located.

Bartlett’s short lament over Mount Zion provides a lot to consider, both in terms of appreciating Jerusalem’s early interpretation history and understanding Bartlett as a historical interpreter. On the one hand, his description of Ottoman Jerusalem cautions against, among other things, misreading the landscape during a short-term visit to the city. Bartlett also provides a reminder of a time when the Western Hill was viewed as a meaningful part of Judahite Jerusalem (Iron Age II). This may prompt us to consider if and how it may have had conceptual value during this period, even if our understanding of Jerusalem’s historical development is altogether different than it was in 1842.

Note: some language in this post was updated since it was originally published.

This annual cycle was no less determinative in the days of David and Solomon than in Bartlett’s. Had he time traveled to ancient Jerusalem in June, I suspect he also would have been disappointed the landscape’s appearance.

Interpretations like these, derived from superficial readings of the biblical material, served as a popular interpretive substratum against which later and more critical understandings of the United Monarchy reacted. Such issues are another set of topics for another post.

This school of thought became known as “minimalism” in the scholarly literature of the 1960s and 1970s.

The ancient core is located instead on the Southeastern Hill, known popularly but erroneously as the City of David.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous posts from this newsletter and follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.