Robinson vs. Williams: Reliving a 19th-Century Topographical Boxing Match

Two scholars writing across the Atlantic in the 1840s sparred over the topography of ancient Jerusalem. A review of their debate is still instructive.

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

The fight of the (19th) century

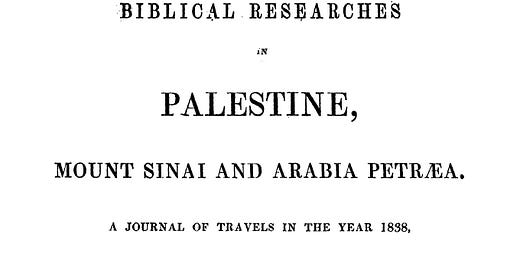

The 1840s played host to a robust topographical debate about Jerusalem. Two contenders rose above others and vied for supremacy. In one corner stood the American titan hailing from Union Theological Seminary in New York, Professor Edward Robinson. After his 1838 trip to Ottoman Palestine with his former student Eli Smith, Robinson published his epoch-making account of their travels in 1841 as Biblical Researches in Palestine (3 Vols).

The two had stayed 19 total days in Jerusalem. During that time Robinson made pioneering observations and reconsiderations of important issues about the city’s history. His conclusions were read widely in the United States and Europe. They challenged prevailing opinions, along with the authenticity of some of the most sacred sites in Christianity. Robinson, therefore, anticipated a potential challenger:

“…intimations have reached me from various quarters, that some of [my] statements and positions in respect to the topography of Jerusalem and some other places, are likely to be assailed, in carrying on a crusade in favour of the reputed site of the Holy Sepulchre." (1843:iii-iv)."

Indeed, a rival soon arose and occupied the opposite corner of the ring. The Cambridge Fellow George Williams had taken up residency in Jerusalem as the Chaplain to Bishop Alexander of Christ Church the very year Robinson’s book was published. Williams made detailed observations during his 14 months in the city, time he believed allowed him to adequately weigh the merit of Robinson’s arguments and come to better conclusions (1845:vii).

He published his own book in 1845 titled The Holy City; or Historical and Topographical Notices of Jerusalem. Its ambitious attempt to recount the entire history of Jerusalem notwithstanding, the book was largely a response to Robinson. Williams did not desire for their topographical disagreements to become a personal feud, but he viewed it as an inevitability due to the popularity of The Biblical Researches (1845:ix). His topographical counterarguments came with accusatory jabs over what Williams considered to be quite overt irreverence. He dubbed Robinson “the champion of novelty” and “chieftain of the unbelieving array” who was "guilty of a most strange perversion of plain facts".1 The fight was on, and Williams had shown that, on issues related to Jerusalem, Robinson faced a committed opponent.

Their match bled into subsequent years, with Robinson replying in two 1846 articles in the journal Bibliotheca Sacra which he founded. Robinson refused to give an inch on any of his major views about Jerusalem. Williams later expanded The Holy City into two volumes (1849) and followed suit in doubling down on all his important topographical positions. Robinson returned to Jerusalem with Smith in 1852 and published Later Biblical Researches in Palestine the following year. His time in the city reconfirmed for him everything he had written about its topography.

This marquee matchup between two scholars spanned the course of a decade. They floated like butterflies, stung like bees, and left thousands of pages in their wake. In this post we take a look at three of their most significant topographical disagreements about ancient Jerusalem.

Round 1: the Tyropoeon Valley

Much of the debate between Robinson and Williams was anchored in divergent readings of a famous passage in The Jewish War where Josephus describes Jerusalem’s geography in detail. He lists hills and valleys by name and even describes selected aspects of their history. In their readings of Josephus, Robinson and Williams differed emphatically about how to identify his geographic terms with the city’s modern landscape. The location of one element in Jerusalem featured heavily in the melee: the Tyropoeon Valley.

Better known as the Central Valley today, Josephus’s debated term “Tyropoeon” is still frequently understood as “the valley of the cheesemakers.” Robinson believed he had identified the course of this valley in a depression surrounding the Western Hill on its north and east sides. He argued that the Tyropoeon Valley began at Jaffa Gate on the far western end of Jerusalem and ran eastward along the David Street bazaar. From there it continued to the Street of the Chain (Bab es-Silsileh) in the area of the Noble Sanctuary and Wailing Wall. It then curved southward and connected with another valley running north-south from Damascus Gate toward the Pool of Siloam.

The first section of Robinson’s Tyropoeon had been lost since the Middle Ages, but recovered by his keen observation. His identification of this valley with Josephus’s Tyropoeon, however, was his own innovation and became associated with Robinson’s idiosyncratic views. For instance, a colorful 1845 review of William’s book appearing in The Dublin University Magazine cleverly referred to his disciples as “Tyropoeonists.”

Williams not only disagreed with Robinson about the location of Josephus’s Tyropoeon Valley. He even denied that the upper part of Robinson’s “Tyropoeon” existed:

"…however "easy to be traced" this valley may be, I must confess that I could never discover it, during fourteen months' residence in Jerusalem, although I must have crossed it almost every day." (1845:268)

Williams referred to the upper part of Robinson’s valley near Jaffa Gate as an “imaginary rectangular substitute” for a valley (1845:391n4). Although he observed, as Robinson had, the precipice on the northern part of Mount Zion, Williams argued that there was no opposite slope in the area around the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Instead, there was simply a flat space filled with rubbish, and therefore, no valley. Williams pointed out that Robinson had strangely ignored a large depression running north-south from Damascus Gate to the Pool of Siloam on bab al-Wad street that clearly severed Jerusalem into two ridgelines. It was in this valley that Williams preferred to locate Josephus’s Tyropoeon.

His response predictably irritated Robinson. Williams had questioned not only his reading of Josephus but also the validity of his firsthand observations in Jerusalem. The existence of Robinson’s upper Tyropoeon was equally as obvious to him as its absence was to Williams:

"...although the Cambridge Fellow "never could find any traces of a valley'' or depression where [my] view places the Tyropoeon,…other[s], not less impartial than himself, both before and after him, have been less unsuccessful." (1846:438)

Each scholar added new supporting arguments in subsequent publications but did not change anything substantive about their basic viewpoints. In the 180 years that have transpired since this debate, scholars have come to accept the existence of Robinson’s valley beginning at Jaffa Gate (against Williams). But resisting Robinson, this depression has been identified as a valley all its own and given a new name of modern convenience (the Transversal or Cross Valley). Josephus’s Tyropoeon seems instead to have run along the route Williams suggested.

Round 2: the Temple Mount and Bridge

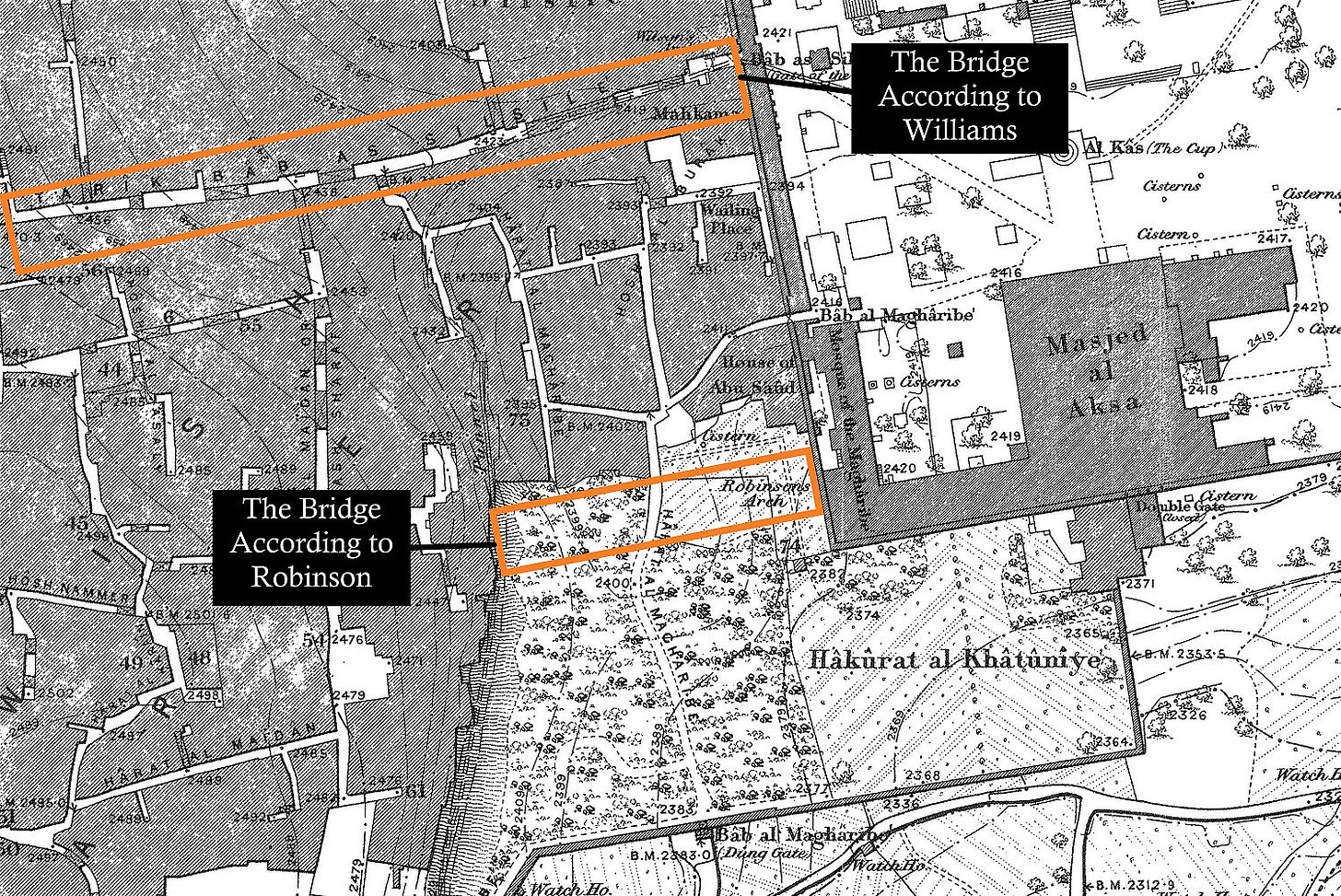

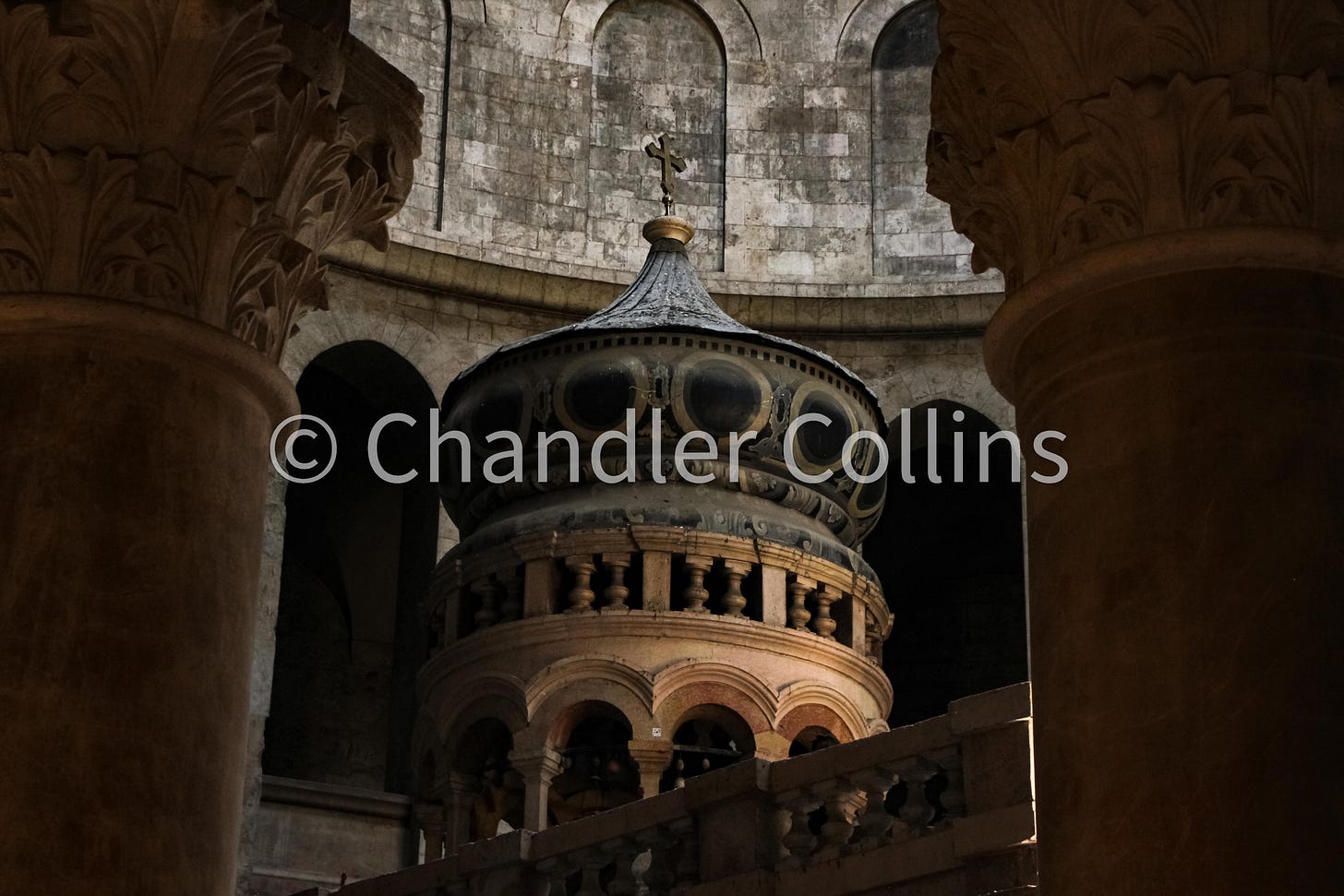

We still associate Robinson’s memory with ancient remains in Jerusalem, the most prominent of which is an arch projecting from the southwestern corner of the Noble Sanctuary. Robinson identified this arch with a bridge mentioned by Josephus in his description of the four western entrances to the Herodian Temple Mount. According to Josephus, this entrance was a causeway spanning the valley between the Mount and Western Hill where Herod’s palace and a wealthy priestly neighborhood was located. I have written elsewhere about how Robinson’s identification of the arch with Josephus’s causeway came to dominate scholarship for some 130 years before archaeology proved him wrong. In the shadow of what seems to have been a near-immediate scholarly consensus, one skeptic countered with insights of his own.

Williams had spent ample time walking around the farmland and prickly pear fields belonging to residents of the Mughrabi Quarter, where Robinson’s Arch was located. He contested its function in light of two original observations. First, there was no evidence of a bridge on the opposite side of the valley where it should have terminated (1845:337). Perhaps more importantly, even if there had once been a bridge in this location, based on the relative height of the arch, it would have led pedestrians to the base of the Western Hill. This position was far too removed to be of any practical use to residents living high on the hill above:

“I have really no wish to exaggerate; but I feel confident that the top of the perpendicular rock of Zion, on the west, can be little short of 80 feet higher than the spring-course of the arch on the east! [If this bridge was level, it] would have landed the passengers in the Tyropoeon, at the foot of the precipice!!” (1845:338n1)

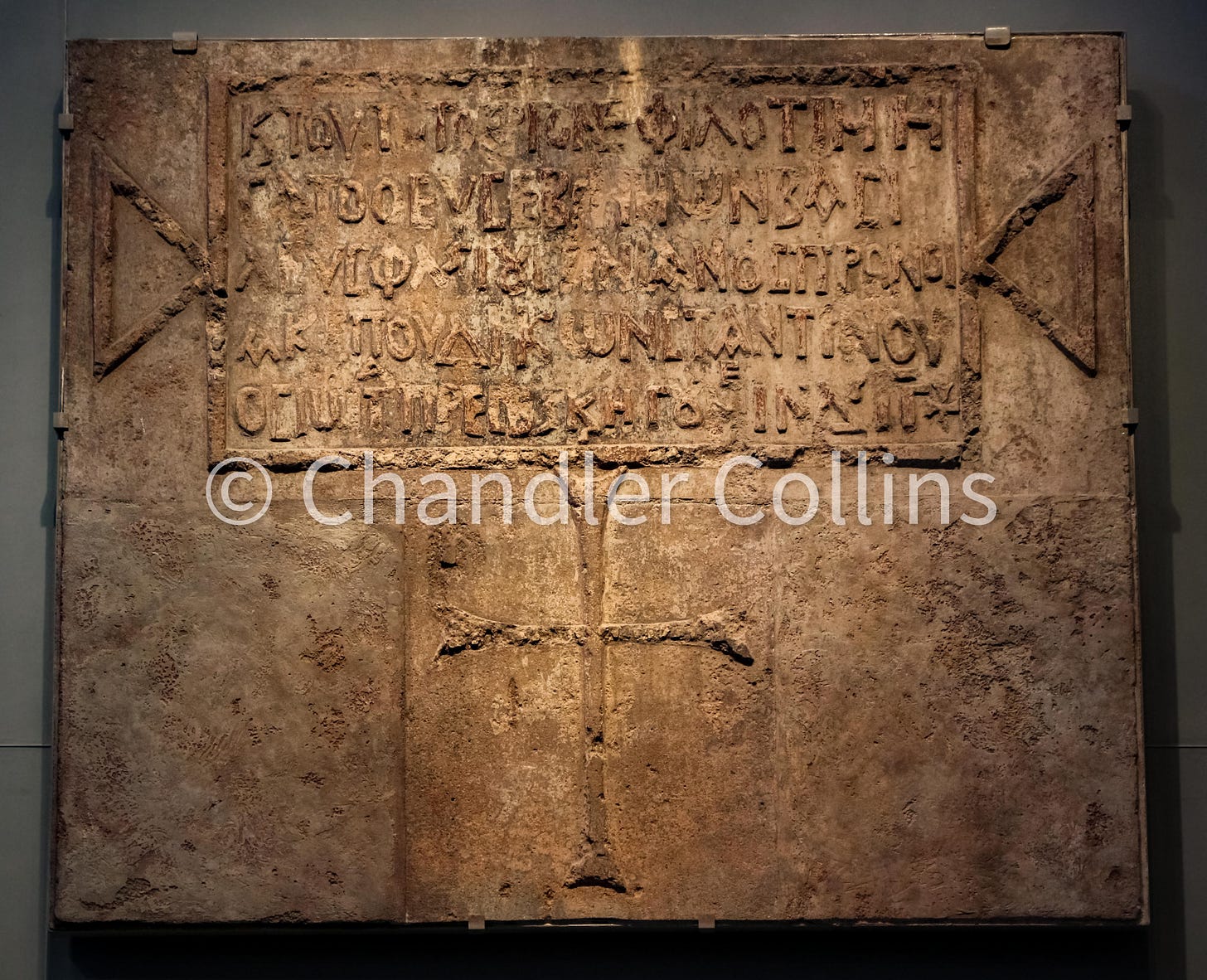

Fascinatingly, Williams reasoned that Josephus’s causeway should instead be located at Bab as-Silsileh street which descends to a western entrance of the Noble Sanctuary by the same name. This street is carried across the Central Valley by a bridge in a manner corresponding well to Josephus’s description.2

Faced with the need to explain the function of Robinson’s Arch, Williams rejected the impulse to identify it with one of the other western Temple Mount entrances mentioned by Josephus. Instead, he made a suggestion that will seem strange to us today. Williams incorrectly believed, like many of his contemporaries (including Robinson), that Justinian’s Nea Church had been constructed in the location where the al-Aqsa Mosque now stands.3 In his view, Justinian avoided building the new church over the former site of the temple because he viewed it as a cursed place, destroyed in line with Jesus’ prophecy in Matthew 24:2 (1845:441).

Working from these assumptions, Williams argued that entire southern portion of the Temple Mount, including Robinson’s Arch, had not been built until the 6th century CE by the Emperor as part of his Nea Church project (1845:331-340). The arch, therefore, could have nothing to do with the bridge mentioned by Josephus which was constructed five centuries before. Williams’s perceptive observations about the location of the causeway have proven correct, even if every element of his reasoning about the dating and function of the arch was not. They were nonetheless unheeded by his contemporaries and forgotten. Robinson’s theory became accepted as fact by all.

Round 3: the route of the Second Wall

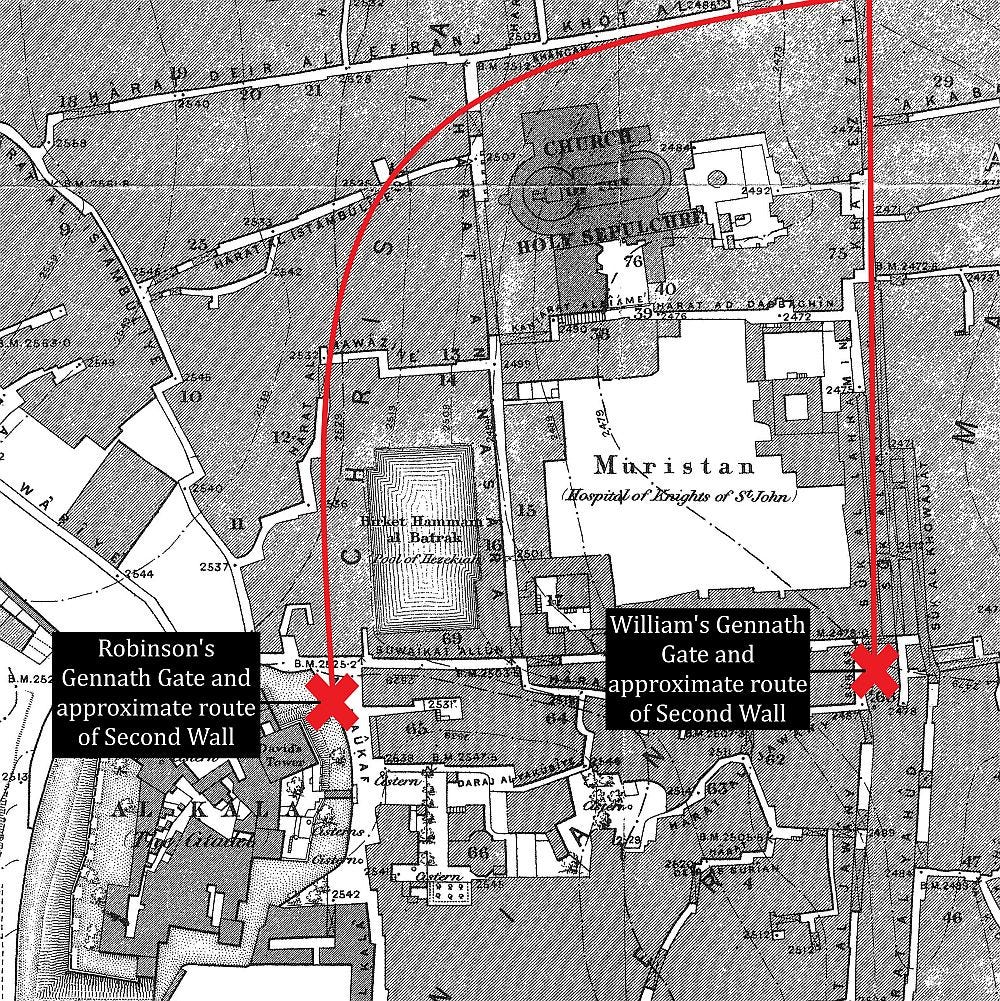

In the topographical debate between Robinson and Williams, no issue was discussed with more passion or at greater length than the route of the Second Wall. This was due to its direct bearing on the authenticity of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the traditional site of Jesus’ tomb. Josephus describes this important wall (termed by him the “Second Wall”) in only one sentence. He says that it ran northward from a gate called Gennath, which was built in the northern fortification wall, and terminated at the Antonia Fortress. The general location of this fortress at the north of the Herodian Temple Mount was not a matter of conflict, even if scholars debated its exact form and position. The location of the Gennath Gate, however, was unknown.

For topographical reasons, Robinson decided to place the gate just east of the Tower of David but before the descent into his “Tyropoeon Valley.” From there, he reconstructed the route of the Second Wall to the Antonia Fortress on a line that swung north of the Patriarch’s Bath and followed the higher ground beyond. Robinson believed this large pool had served as an important source of water in Jerusalem since Hezekiah’s time and would naturally have been protected. This trajectory enclosed the area of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher within the city’s fortifications. Because the gospels imply and Hebrews states that Jesus had been crucified outside the walls of Jerusalem, Robinson’s historical reconstruction disqualified the most important church in the Christian world from its historical claims:

"Thus in every view which I have been able to take of the question, both topographical and historical, whether on the spot or in the closet, and in spite of all my previous prepossessions, I am led irresistibly to the conclusion, that the Golgotha and the tomb now shown in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, are not upon the real places of the crucifixion and resurrection of our Lord. The alleged discovery of them by the aged and credulous Helena, like her discovery of the cross, may not improbably have been the work of pious fraud. (1841.2:80)

Lying behind this topographical interpretation was a committed Protestant whose attachment to the Bible was supreme. He believed that pilgrim routes and traditional sites obscured the true locations of biblical events and therefore assigned them little value or emotional attachment.4 On some pages of The Biblical Researches, Robinson went even further and expressed disgust at the communities who worshipped in the Holy Sepulcher.5 After describing the “mockery” of the Holy Fire ceremony and the “mummery” of the Latin Catholics that took place at Easter in April 1838 (1841.1:329), he noted:

“The whole scene indeed was to a Protestant painful and revolting. It might perhaps have been less so, had there been manifested the slightest degree of faith in the genuineness of the surrounding objects ; but even the monks themselves do not pretend, that the present sepulchre is any thing more than an imitation of the original. But to be in the ancient city of the Most High, and to see these venerated places and the very name of our holy religion profaned by idle and lying mummeries ; while the proud Mussulman looks on with haughty scorn ; all this excited in my mind a feeling painful to too be borne; and I never visited the place again." (1841:331)

Despite Robinson’s insistence elsewhere that he carried no prejudice in the matter, many have noted that comments throughout The Biblical Researches suggest otherwise.6 This understanding proves important when reading seemingly unrelated topographical discussions that in fact had a direct bearing on the church’s authenticity.

Though a Protestant himself, Williams was quite offended at Robinson’s criticism of both early Christian sources and the modern ecclesiastical establishment. He reserved his most severe accusations for these instances.7 He wrote, for example, that Robinson had unwittingly aligned "himself with the disciples of the Koran and the Crescent, the avowed enemies not of the Sepulchre alone, but of the Holy Church Catholic." (1845:ix). The American scholar had maligned the "great men" of church history, and Williams was "too deeply indebted to the Nicene age to hear its most distinguished doctors calumniated and feel no interest in the quarrel" (1845:vii).

Regarding the pertinent topographical issues, Williams pointed out that Robinson had stated, but not adequately defended, his idea that the Gennath Gate was located near the Tower of David (1845:264). Williams argued cogently that this area would have been a poor location for a public gate, given that, according to Josephus, Herod the Great’s palace stood on its inner side. Three large towers were also built in this space in line with Jerusalem’s northern fortification wall. The area also teetered on the edge of a precipice that was called alternatively the Tyropoeon by Robinson and a depression by Williams. It was, then, very unlikely that a public gate would be located here:

"The absurdity of supposing an exit for a city-gate through such a royal palace, and down a precipice of thirty feet, is obvious, and need not be insisted on." (1845:262)

Williams preferred to find the Gennath Gate much further east of Herod’s palace where the topography leveled out near the Three Bazaars. He drew the line of the Second Wall northward from there, leaving the Holy Sepulcher outside the city. Williams believed he had proved the church’s claims to authenticity, when he had only shown they could not, in all likelihood, be discounted on topographical grounds.

Robinson reiterated his views about the location of the Gennath Gate and Second Wall in future publications, of which his return trip to Jerusalem in 1852 thoroughly reassured him. Though Robinson did not advocate a rival site for the Tomb of Christ, his argument undoubtedly contributed to the broad acceptance of a new Calvary among Protestants within only four decades. However, time and the accrual of more data has shown that the topographical assessment by Williams is much more likely. Today the majority of scholars locate the Gennath Gate near the area where Williams placed it.

The Judges’ Table

Reflecting on these disagreements with the benefit of hindsight derived over the last 180 years, it is easy to understand how each scholar missed the mark on any given issue. Sometimes their discussions led them in the right direction but for the wrong reasons. Judged from the perspective of their own time and near total lack of archaeological resources, their command of the available historical sources (in their many original languages) and Jerusalem’s visible topography is remarkable.

In the absence of a TKO, I assume that Robinson was considered the winner by (public) decision. This was as true in his own time as it is in present memory. (How many today even know the name George Williams, much less his ideas about Jerusalem?) He could not match Robinson’s overall acumen blow for blow and had little chance of convincing a field that he dominated. However, a close reading of Williams suggests that he held his own with regard to the topography of Jerusalem.

The colorful exchange between these scholars took place as the city was opening up to western travelers and “scientific” inquiry. Though their fight is long over, a review of this topographical boxing match over Jerusalem is more than a spectacle. Their exchange set the trajectory for questions that would continue to be unpacked by future explorers and archaeologists and that in some ways reverberate to our own day.

One feature making these publications so colorful is the way each scholar refers to the other, almost always in the third person and in an array of interesting names.

This was more than twenty years before Charles Wilson would find the spring of an arch that is called by his name today. The long-debated date of construction for Wilson’s Arch has recently been shown to be the first century CE.

Remains of the Nea Church were later unearthed in Nahman Avigad’s salvage excavations during the reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter after 1967.

His moment of reflection, inspired by the bare landscape around the Garden of Gethsemane, is a notable exception (1841:347).

Attempts to minimize this issue or suggest it was not influential in his reconstruction of the route of the Second Wall are unconvincing.

A similar charge may be brought against Williams who expressed a very strong appreciation for the Sepulcher. An evaluation of each scholar in the matter must be based on a detailed study of their writings.

In the second edition of The Holy City, Williams issued a long apology for the tone in the first edition.

Enjoy the post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous editions of this newsletter or follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.

I think this may be your best post so far! Sounds like for these three issues it was a TKO for Williams.