Breadcrumbs at Jaffa Gate

Scars embedded in the Old City wall at Jaffa Gate serve as windows into memories of Jerusalem's recent past. This post explores three examples.

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

The Old City’s only western entrance at Jaffa Gate draws its fair share of foot traffic. Pedestrians streaming along the Old City walls or passing through Mamilla Mall below enter the gate to access a variety of tourist and holy sites, markets, and residential areas. Tour groups gather in the open plaza outside the gate to begin their itineraries, and faux-guides advertise their services to unsuspecting visitors catching their first glimpse of the Old City. Generally only one street vendor utilizes the area, an Arab baker selling Jerusalem bagels (ka’ak). He strategically shifts his location, leveraging the shade outside the gate in the morning and inside during the afternoon. The lack of historical signage around Jaffa Gate does not naturally invite pause or reflection aside from a view of the gate itself or the nearby lookout into the Hinnom Valley (Wadi er-Rababa). With no cafes or restaurants in the immediate proximity—and little available shade—Jaffa Gate is more a thoroughfare than destination.

Pedestrians who move through the gate may not be aware that they pass by several small but important incisions left in the wall by recent historical processes. With proper reflection, these breadcrumbs embedded in Jerusalem’s architecture can lead us toward a better appreciation of the city’s history. In today’s newsletter, I want to pause at Jaffa Gate and take a brief look at three of them and the important windows into Jerusalem’s past they provide.

Opening the Wall

Unlike at most other gates of the Old City, pedestrians at Jaffa Gate may choose between two entrances—either the original bent-axis gate proper or a breach in the wall between the gatehouse and the Citadel walls where the modern road is paved. Since fortifications are never built with gaps, we may surmise that this opening at Jaffa Gate was made for a specific purpose during a time of peace. As is widely known, the creation of this new access point took place in 1898 as part of the preparations for the visit of Kaiser Wilhelm II who inaugurated the Church of the Redeemer on October 31.1 The opening in the walls allowed the Kaiser and his entourage to ride comfortably into Jerusalem on horses and carriages. Conrad Schick detailed these changes and even provided a map illustrating them.2

While it is often said that “a breach was made in the walls” for the Kaiser’s visit, this is only partially correct. Because the Ottoman city wall was not built very high in this location, five or six courses at most needed to be removed to accommodate the German ruler. The reason for the unimposing height of the wall here was the deep moat located outside the gate (today buried under the modern road). The bulk of the preparatory work was actually filling in this most rather than knocking down the wall.

Evidence of the shortening of the wall can still be see in an irregular pattern of stones on the southern face of the gatehouse to which the wall originally connected. A small trench cut into the modern paving stones along the road traces the original location of the city wall. Pedestrians winding through the interior of the gate itself, or simply passing over the 1898 breach in a hurry will not notice them. Nonetheless, they are physical reminders of what was an important event in Jerusalem, illustrating the growing imperial interest in the city at the end of the 19th century.

A Shared Center

In addition to the new settlements and compounds built outside Jerusalem’s walls from the middle of the 19th century on, the city also began to expand organically from the inside out. The outgrowth at Jaffa Gate catalyzed the development of a shared public center, including a water fountain, clock tower, the municipal building, banks, cafes, post offices, and a number of other important establishments (see further details here). This urban growth around Jaffa Road was appropriate geographically as it was the meeting point between the city and commercial traffic arriving from the Mediterranean coast. Today only a few buildings from Jerusalem’s Late Ottoman public center remain below in the newly built Mamilla Mall. Some were moved there in order to be preserved, such as the Stern House where Theodor Hertzl stayed during his first visit to Jerusalem in 1898, deliberately coinciding with the Kaiser’s arrival (see above). So what happened to Jerusalem’s shared public center?

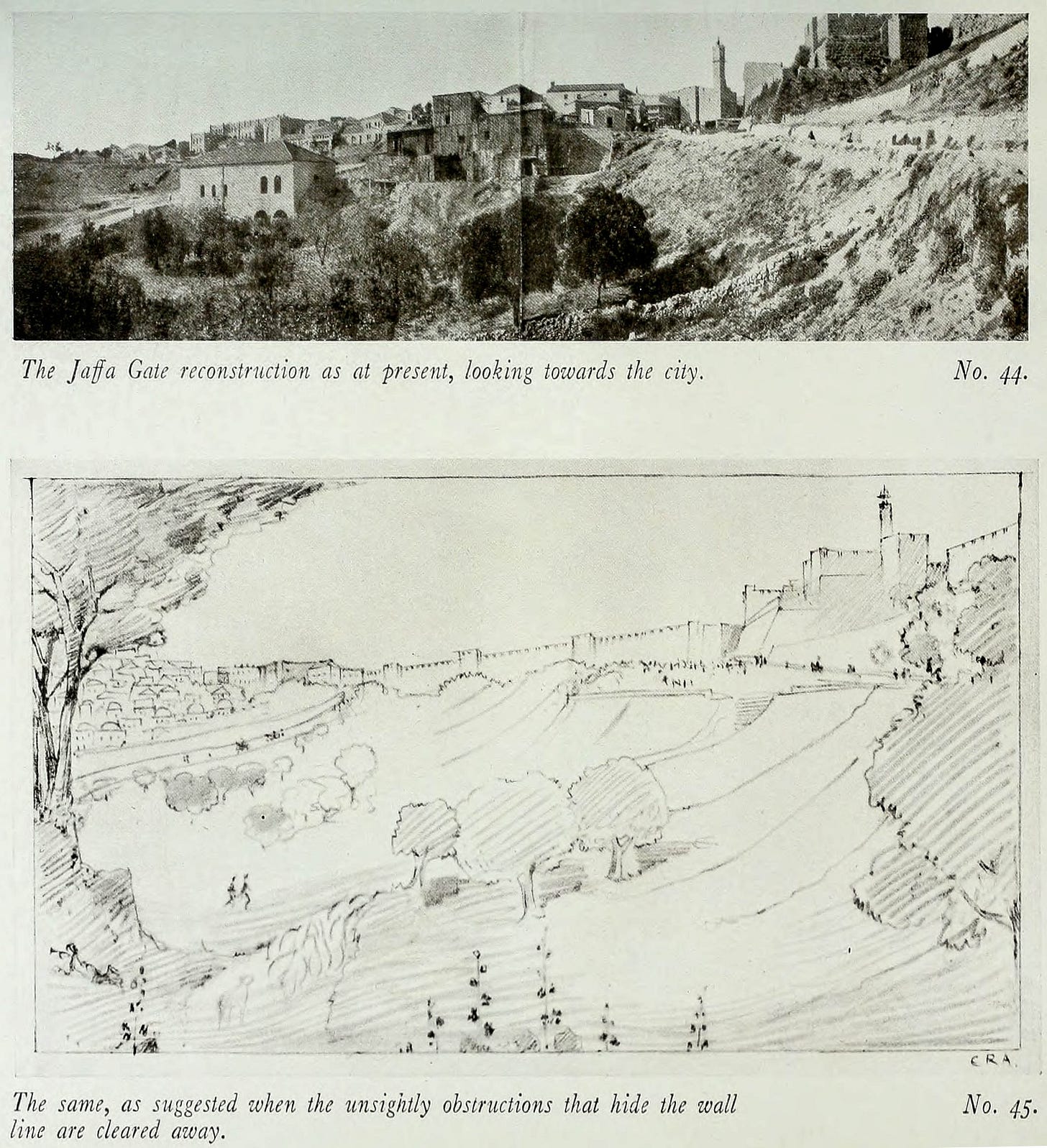

During the British Mandate Period, the architect Charles Ashbee envisioned a future where the visibility of Jerusalem’s Old City walls would eventually require the destruction of buildings obscuring it. Though his plan was not entirely realized during the Mandate Period, the wheels were put in motion. The clock tower and water fountain were dismantled, and key institutions were moved from this area to other locations, slowly removing the civic importance of this shared center (Wallach 2020:149). It later fell into disrepair after the events leading up to 1948 and sat in No Man’s Land during the years of Divided Jerusalem. The buildings along the Old City wall were dismantled after 1967, and over the course of several decades following, the Mamilla Mall was planned and eventually built at its foot, leaving the wall above unobscured. Although arising from historical mechanisms not directly related to Ashbee, the spirit of his original urban plan for the area had been fulfilled. Standing in the empty plaza outside Jaffa Gate today, visitors grasp neither the area’s former importance nor the circumstances of its undoing.

Although Jerusalem’s Late Ottoman center has been long removed, some cuttings in the wall outside Jaffa Gate show outlines of a few buildings that made up this area in the 19th century. The photos below demonstrate two such examples. Perhaps others can be found along the wall further west.

Marking Sea Level

Our last architectural breadcrumb is a small incision outside Jaffa Gate on its bottom right jamb. This chiseled work is a “bench mark” that was cut into Jaffa Gate during the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem. This mission took place in 1865 and was led by British Royal Engineer Charles Wilson. Wilson sought to thoroughly explore Jerusalem and its environs with the ostensible goal of improving the city’s water supply. Wilson’s survey reports about Jerusalem covered various aspects of the terrain, architecture, and population but also emphasized the historical and biblical importance of his explorations. The mission’s success was the springboard for the formation of the Palestine Exploration Fund later that year.

The most important products of this mission were the extremely accurate maps and plans of Jerusalem based on the high survey standards of British Royal Engineers. Due to its topographic accuracy, the Ordnance Survey Map came to be used widely by geographers and historians of Jerusalem after its creation, and it remains useful today. However, Wilson’s map imposed the popular four-quarter division onto Jerusalem, something that was totally foreign to the city’s inhabitants (see more here). Nevertheless, for the first time, a map of Jerusalem was created that included precise elevations above sea level. These elevations were ascertained literally by walking between Jerusalem and the Mediterranean Sea with sticks and chains in hand, marking the changes in elevation as they went (“leveling”). The expedition also leveled down to the Dead Sea.3

At some places along their routes between the seas, as well as in Jerusalem, Wilson's team incised bench marks from which they took elevation readings. These bench marks consist of two parts: an arrow pointing upward and a horizontal bar above it (see photo below). An angle iron was inserted into the horizontal bar which served as a “bench” for the leveling stick. The example at Jaffa Gate is one of a small number that have survived from this watershed survey that mapped Jerusalem as it was beginning to expand outside the city walls in the 19th century.4 The mark is also a witness to Jerusalem's Late Ottoman past, since the majority of the Old City roads and architecture remain exactly as they did in 1865.

Slowing Down and Looking Up

These examples of scars in Jerusalem’s wall invite us to keep our heads up while walking in the city and to pay attention to the details we may encounter. As in many other places in Jerusalem, items two and three above are not accompanied by historical signage informing visitors of their importance. In such cases, passers by have only one tool at their disposal—their eyes. In Jerusalem, even the smallest incisions can tell important stories about the city’s past. If we are mindful, we can come to appreciate what they have to impart.

The American Colony Photo Department captured various aspects of the Kaiser’s visit to Ottoman Palestine.

The road was also widened near King David’s Tomb so that the Kaiser could visit land on Mount Zion that would be gifted to Germany during his trip. The land, which would become the future home of the Dormition Abbey Church, included the American Cemetery where Horatio Spafford and other members of the American Colony had been buried. They were reinterred in the Protestant Cemetery and buried in a mass grave after their bodies were mixed together during their excavation (Spafford Vester 1950:199ff.).

Wilson’s team was not the first to level from the Dead Sea to the Mediterranean. As far as I know, this was initially completed by the American W. F. Lynch in 1848 on an official U.S. Navy expedition that sailed the Jordan River from the Sea of Galilee to the Dead Sea.

About a half million bench marks of various types were made throughout Great Britain.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous editions of this newsletter or follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.