In Search of Josephus' Gennath Gate

Jerusalem's elusive Gennath Gate is mentioned only once by Josephus. Scholars have proposed many different locations for it, but all of them share a common geography.

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

In his book on the war between the Jews and the Romans, the first-century historian Josephus mentions a gate in Jerusalem called the Gennath Gate that is otherwise unknown. Although Josephus wrote in Greek, scholars understand the word “Gennath” to be a reflection of an Aramaic word meaning “garden” (Kelley 2019:72n14) It is often referred to as the “Garden Gate” for this reason. On the analogy that ancient city gates are usually named for what they lead to upon exiting them, most scholars assume that there was a cultivated area outside the Gennath Gate which gave rise to its name (more on this below).

In the context surrounding Josephus’ mention of the Gennath Gate, he describes three different walls that surrounded Jerusalem as the Roman army approached the city to begin their assault in 70 CE (see this map which shows one interpretation of the “first wall,” “second wall,” and “third wall”). Based on the details in Josephus, all scholars agree that the Gennath Gate stood in the northern line of the oldest of these three walls. This would place the gate somewhere between today’s Jaffa Gate and the Noble Sanctuary (near Wilson’s Arch) where pieces of the wall have been uncovered in excavations. Contextual clues in Josephus and in the geography of this area probably put the Gennath Gate somewhere in the middle, and a perusal of the literature about the location of the gate shows that most scholars follow this logic.

Based on this understanding, Shimon Gibson describes the geography around the Gennath Gate in his book The Final Days of Jesus this way:

“…a valley existed on the north side of the First Wall and extended eastward down to the Tyropoeon Valley. It is referred to by scholars as the Transversal Valley, but is not mentioned in ancient sources…at the top of this valley, to the west, there was a very large open reservoir of water, known as the Amygdalon (“Towers”) Pool, mentioned by Josephus (War V.468). The situation of this pool would have made it fairly easy to establish terraced orchards and gardens, irrigated with channels leading from the pool, descending in serried fashion down the length of the upper Transversal Valley towards the Gennath Gate. These terraced gardens would have been the reason for the name of the gate." (Gibson 2009:119)

This is just one understanding of the hypothetical physical setting of the gardens that gave rise to the toponym “Gennath Gate.” Although this reconstruction is certainly possible, to my knowledge there is yet no evidence of agricultural terraces near the pool mentioned by Gibson. Another idea is based more concretely on the archaeological evidence of stone quarries that were found throughout this area in several places. This suggests that bedrock may have been exposed in a broad area, along with pockets of soil that could have been cultivated (Kelley 201972n14). In an article about the Garden of Uzza—mentioned in II Kings 21:18 and 21:26 as the burial places of Judahite kings Manasseh and Amon—Francesca Stavrakopoulou explores the history of mortuary gardens, which served as beautified places for venerating dead kings. She mentions that the gospel writer John may have such a place in mind when he described the tomb of Jesus in relationship to a garden and noted that Mary Magdalene confused him for a gardener (John 19:41; 20:15).

Josephus also tells us that the Gennath Gate served as the beginning of another wall that ran north, the so-called Second Wall. Although Josephus introduces us to the Gennath Gate in the context of the Second Wall, it is important to remember that it was actually a preexisting gate which was built into the First Wall. Conclusive remains of the Second Wall have never been found, but that has not stopped scholars from proposing many different hypothetical routes based mainly on the topography (see one example here).

The large amount of ink that has been spilled over the Second Wall is due to the fact that the route of this short wall is an important piece of evidence for locating the historical location of Jesus’ crucifixion and tomb which the New Testament says was outside the city. John’s location of Jesus’ tomb in a garden, Josephus’ description of a Garden Gate, and the nearby Church of the Holy Sepulcher which houses the traditional Tomb of Christ is its own web of tantalizing connections. Getting into these topics would take far more space than is allowed in this short article, but the video below is a helpful introduction to them (I was the main writer for its script).

Proposed Locations for the Gate

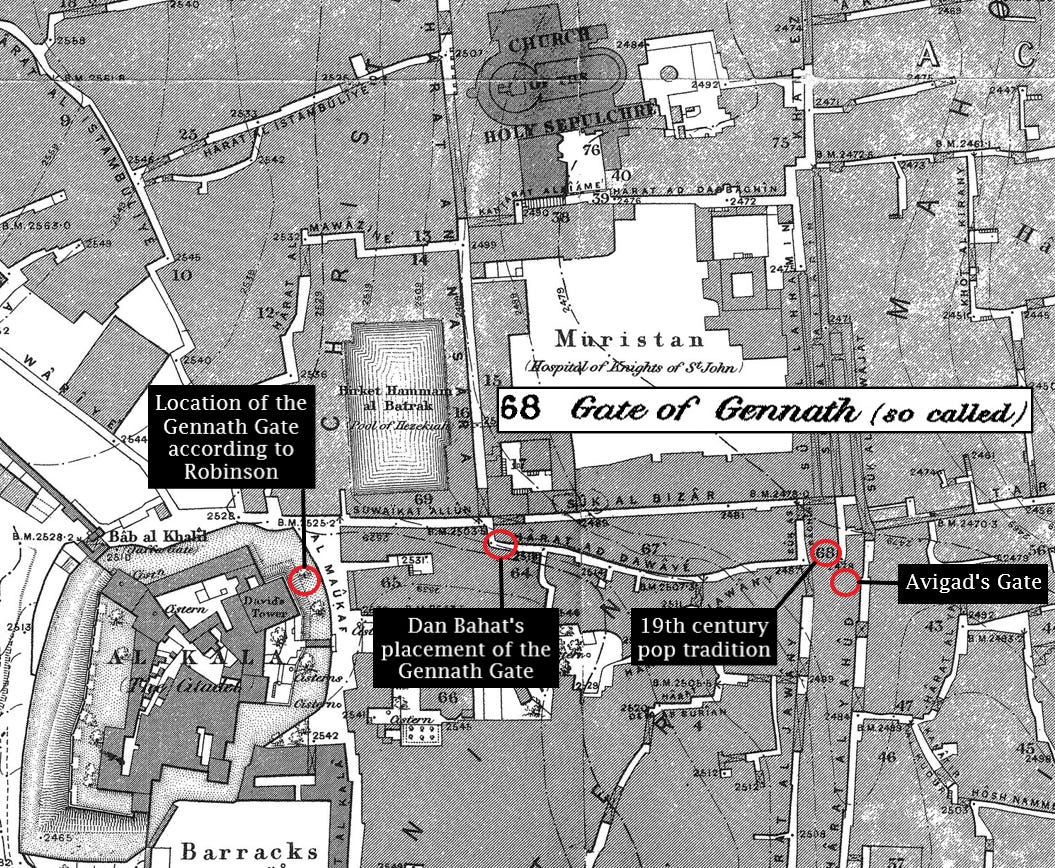

Returning to our original question, although scholars have proposed many different locations for the Gennath Gate, they are all along the same line of topography on the northern edge of Jerusalem’s Western Hill. Anchored on the edge of the hill, the wall built here could take defensive advantage of the so-called Transversal Valley that sat below it.

On the far western end of the fortification line, Herod built his palace and monumental defensive towers, one of which is preserved in the Tower of David. The American scholar Edward Robinson, who made several important contributions (some of which created controversy) to the study of ancient Jerusalem, located the Gennath Gate in the immediate vicinity of the Tower of David. This theory cannot be separated from his disdain for the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and its historic Christian communities. His conclusion that the Gennath Gate sat near the Tower of David, allowed him to draw the line of the so-called Second Wall so that it included the Holy Sepulcher within the city and thereby disproved the authenticity of the traditional Tomb of Christ. Robinson’s idea was based on a reading of Josephus that makes all three walls of Jerusalem begin at the same point, something that is never claimed in the text. Although some scholars followed Robinson’s location of the Gennath Gate, the majority—even in his own day—pointed out the large problems with it. For this reason almost all scholars seek the Gennath Gate elsewhere.

A local popular tradition that was probably alive in Jerusalem during Robinson’s 1838 visit understood the contours of an arch visible along one of the city streets to be the remains of Josephus’ gate. Charles Wilson, who surveyed Jerusalem in 1865 and made the first modern maps of the city, labeled this arch the “Gate of Gennath (so called).” In the following years, his colleague Charles Warren did some digging near the arch, and for this reason, he is sometimes mistakenly thought of as its discoverer.

When and how this 19th-century tradition relating to the Gennath Gate developed does not seem clear. After 1967, the area of this arch was reexcavated. It is thought by most scholars today to be part of a building which dates either to the Byzantine or the Early Islamic Period rather than a fortification. Interestingly, Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah believes this could be the northern gate of the Tenth Roman Legion’s camp which was built to house this legion in Jerusalem after the city was destroyed in 70 CE (2020:29). But however we slice it, everyone agrees that this arch and the entrance below it cannot be the Gennath Gate of Josephus.

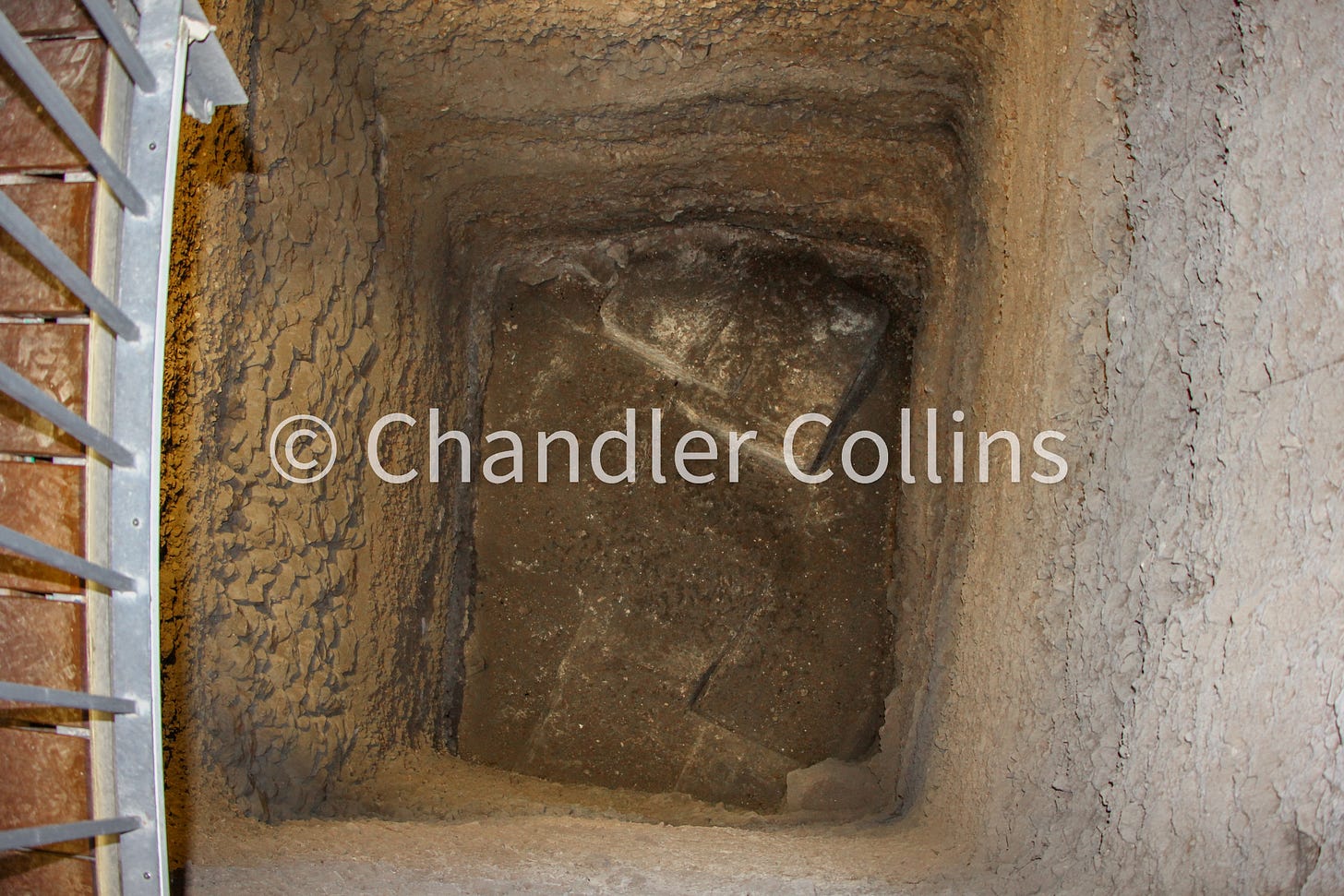

The current majority view among scholars and only other tangible option for the Gennath Gate that I am aware of sits just east of the arch mentioned above but much lower in elevation. During the years following 1967, Nahman Avigad excavated here as part of the reconstruction and expansion of the historic Jewish Quarter. In this location which sits below a Crusader market, his team uncovered part of the line of wall in which the Gennath Gate should have been built according to Josephus. An opening between the walls was found without any of the typical architectural remains that would indicate the existence of a gate (such as a pier or threshold), Avigad interpreted the opening as a gate and also identified it with the Gennath Gate. Today most scholars accept Avigad’s interpretation and consider it the best candidate for the Gennath Gate (Gibson, Wightman, Murphy-O’Connor, Kelley, Cabaret, etc).

However, as hinted above, there was no archaeological smoking gun to suggest that a gate had been located here or that it could be connected certainly with the Gennath Gate mentioned by Josephus. Avigad disseminated his interpretation most widely in his popular book Discovering Jerusalem which was published in English in 1983. It is worth examining his full statement to see how tentative it is:

"The gap between the line of this wall and that of the parallel fragment 7 suggests that a city gate may have been located here. Topographically, the ravine could have provided a suitable setting for such a gate on the north, a possibility which we have already noted in conjunction with the Israelite fortifications. If our assumption is correct, we might identify this gate with the much discussed "Gennath Gate" mentioned by Josephus as being located in the northern line of the first wall; at the point of junction with the second wall, which enclosed a quarter of the city to the north." (Avigad 1983:69; emphasis mine)

The bolded words show that Avigad was aware that he was making an archaeological interpretation of these remains based on cumulative evidence rather than conclusive evidence. Avigad also assumed the existence of two other gates in other nearby walls from the time of the Judahite Monarchy (Iron Age), including in his so-called “Broad Wall.” The final excavation report, published in 2000, did not add any substantial new information.

For these reasons, some scholars do not accept Avigad’s interpretation of the gate (Bahat, Galor and Bloedhorn). I tend to find myself among this small group. Although the location of this find fits the requirements of Josephus and agrees with the geography well, the material remains seem less clear. The shape of the opening in Avigad’s Gennath Gate also seems unusual, and it runs east-west rather than north-south as might be expected. Perhaps the gate is here or directly nearby but could not be clarified because of the limited area that could be excavated.

So where does that leave us? Actually, in a pretty good place. The dispute about the Gennath Gate is not like other aspects of Jerusalem’s history and archaeology (such as the course of the Second Wall) where scholars propose wildly diverse interpretations or locations for a given structure. The difference in placement for the Gennath Gate today comes down to an area around 500 feet (ca. 150 m.), all along the same line. This densely built part of the city is unlikely to yield a definitive archaeological answer in the future. We may need to be satisfied in knowing that we have a much more limited range of variables associated with the location of the Gennath Gate than we do for many other issues related to ancient Jerusalem.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous editions of this newsletter or follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.