Jerusalem in Brief (No. 7)

The construction of Herod's Temple Mount, maps and plans from Charles Warren, and a reflection on the Gennath Gate

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription and receive unique Jerusalem-related benefits.

Jerusalem visualized

This photo shows the ca. 35-acre Herodian Temple Mount platform as depicted on Michael Avi-Yonah’s famous model at the Israel Museum (I’ve written some elsewhere about the model’s background, which I will not explore here). The Mount is shown after it was enlarged during the first century BCE/CE with its well-known buildings (from left to right): the Royal Portico, Temple, and Antonia Fortress. Smaller porticoes line the compound’s outer edges with massive retaining walls below.

A number of sources inform us about the Herodian Temple Mount, including ancient texts, the topography, material remains uncovered in excavations, and the architecture visible in the sacred enclosure of our own day. Perhaps the most important source is Josephus who provides detailed descriptions of Jerusalem’s major structures prior to the assault by the Roman army in 70 CE. His memories of the temple compound presented in The Wars of the Jews (book 5) and Antiquities of the Jews (book 15) are indispensable.

The depiction of finalized architecture on the Herodian Temple Mount in Avi-Yonah’s model is of immense value, not only for illustrating Josephus’s memory of Jerusalem but also for gaining a sense of the major features built in the enclosure. Without intending to detract from the model’s achievement or its helpful illustration, I think it is important to balance this depiction by considering how Herod’s project would have been experienced in real time. In the paragraphs below, I will discuss a historical nuance the model does not aim to capture, namely the Herodian Temple Mount as a kind of iterative construction site.

Josephus gives us some information about the duration of the Herod’s grand project, and scholars have discussed the topic at length. It is usually assumed that Herod initiated construction in 22 BCE (War I.401). However, it seems safe to suppose that the Antonia Fortress would have been built earlier, as Mark Antony, for whom the structure was named (Ant. XV.409), died in Egypt in 30 BCE.1 Josephus says that the temple proper was built in a year and a half (Ant. XV.421), and that the cloisters and outer enclosure, including the Royal Portico, took eight years to build (Ant. XV.420). However, in another place (Ant. XX.219), he writes that the whole project was not completed until much later, during the time of Herod Agrippa II (Herod the Great’s great grandson) in the 50s CE (Reich and Baruch 2019:159). What can archaeology contribute to this contradictory timeline in Josephus?

Excavations in 2011 near the southwestern corner of the sacred enclosure (beneath Robinson’s Arch) exposed a Jewish ritual bath (mikveh) that had been sealed before this section of the retaining walls was constructed. Among the finds from the mikveh was a coin minted at the earliest in 17/18 CE.2 The find implies that the building of this section of retaining walls, upon which the massive and ornate Royal Portico was constructed, could not have begun until after that time. Many scholars have since accepted that the Royal Portico was not completed until after Herod’s death in 4 BCE (Reich and Baruch 2019:159; Peleg-Barkat 2017:92; Magness 2024:233).3

Further north, near the northwestern corner of the same line of retaining walls, construction efforts encountered a large bedrock spur which I refer to elsewhere as the “Fortress Saddle.” The evidence here indicates that, in addition to being partly quarried, much of the spur’s outer face was carved into the form of Herodian stones in order to visually integrate it with the rest of the western retaining wall. However, exposed bedrock in the Western Wall Tunnels shows that pieces of this outcrop were left unworked when the entire structure was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE (Magness 2024:233). In other words, even the “final form” of this section of the Herodian Temple Mount seem to have featured chunks of roughly shaped limestone rather than the smooth, ornate stones typically associated with the retaining walls. The work here was apparently never completed.

These examples suggest that the construction process of Herod’s Temple Mount unfolded in a manner that coheres well with the oft-referenced statement of the Jerusalemite leadership in John 2:18:

“This temple has been under construction for forty-six years, and will you raise it up in three days?” (NRSV).

Josephus offers a less precise but similar remark in a section describing the construction of the retaining walls, after which he concludes:

“…what could not be so much as hoped for as ever to be accomplished, was, by perseverance and length of time, brought to perfection” (War V.187).

How much time, exactly? Estimates vary, but scholars seem now to generally agree that construction continued into the first century CE. In an article that aims to outline the exact progression in which Herod’s project was built, Ronny Reich and Yuval Baruch estimate that the project lasted 50 years or longer (2019:159). In Orit Peleg-Barkat’s collation of the ca. 500 known fragments of the Royal Portico, she hints at a similar timeframe using historical parallels (2017:92).

This decades-long undertaking progressively altered the appearance of the Mount and opened a perpetual construction zone near the temple. The project would have created inconveniences for visitors, even if the rituals themselves were not interrupted and work was paused during festivals. It is interesting to consider how Jewish pilgrims living outside Judea might have encountered the Herodian Temple Mount during one or more annual visits in this period. Each return to Jerusalem would have confronted them with a new iteration of construction progress and a social context in which the project would have undoubtedly been discussed.

It seems likely that Josephus’s description of the enclosure is probably most relevant to those who would have seen Herod’s Temple Mount in the years or decades leading up to 70 CE. The platform shown on Avi-Yonah’s model helpfully portrays that moment in time but probably does not represent the experience of most people who visited Jerusalem between the initiation of Herod’s grand project and its destruction. A model that sought to convey this experience might incorporate scaffolding, crews of workmen, chisels and other tools, visible quarries, stones being moved into place, and temporary routes to the temple that avoided the construction.

The progressive unfolding of Herod’s project and its real-time experience deserves to be explored in more detail. This short entry provides some historical context for the many depictions of Herod’s Temple Mount which, like Avi-Yonah’s model, emphasize its completeness. As a complement to those portrayals, we reflected instead on what was probably one of the monument’s most visceral qualities in antiquity—its becoming.

Internet Standout

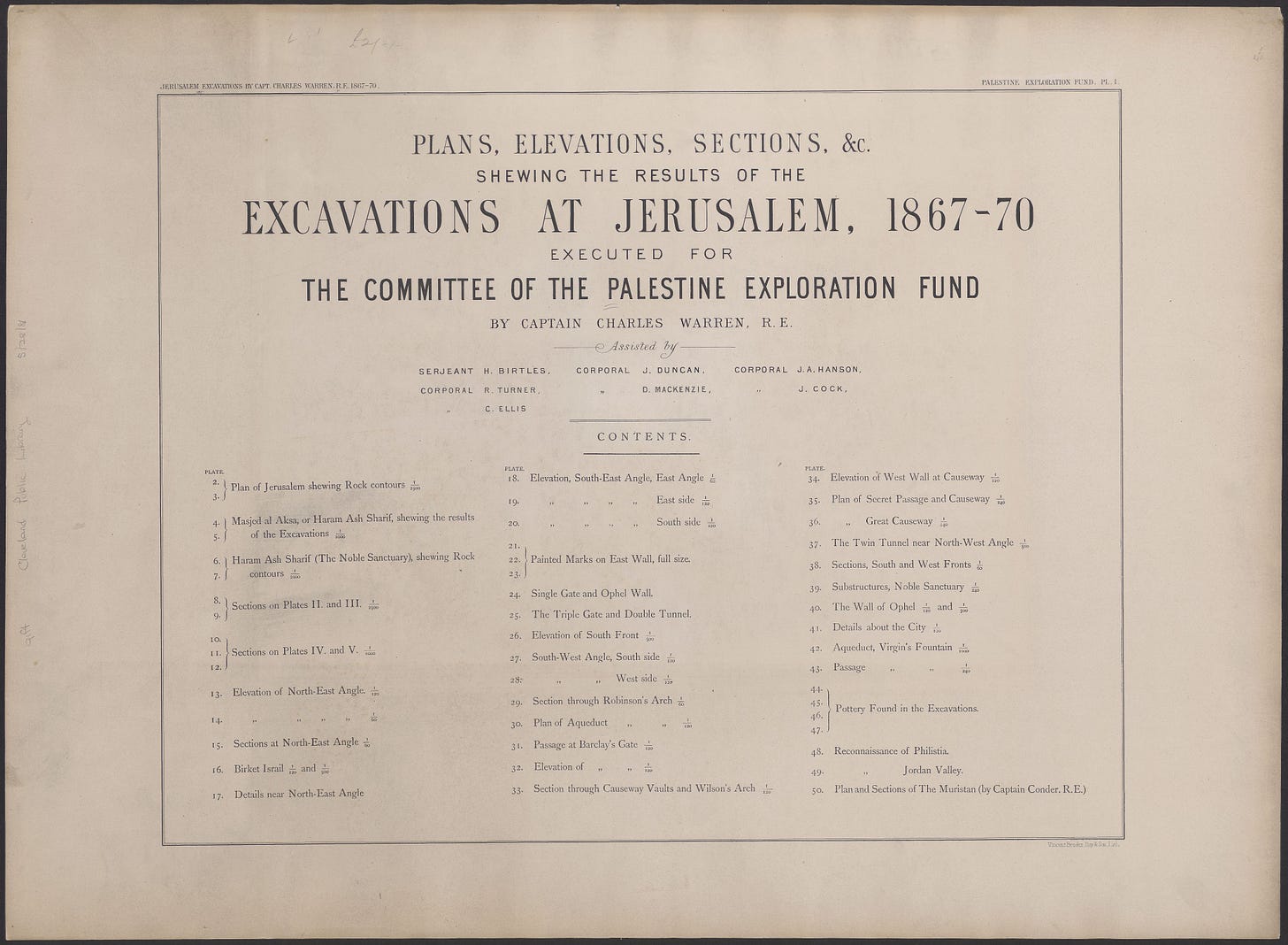

British Royal Engineer Charles Warren excavated and surveyed in Jerusalem from 1867-1870, most famously tunneling along the retaining walls of the Noble Sanctuary. Several books related to his work in Jerusalem were published, including Plans, Elevations, Sections, &c. Shewing the Results of the Excavations at Jerusalem, 1867-70 Executed for the Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund in 1884. This work includes 50 plates with maps and illustrations drawn by Warren, most of which pertain to his activity in Jerusalem. In part due to their accuracy, Warren’s plans are still referenced by scholars who study ancient Jerusalem. An original copy is available for purchase to the exorbitant tune of € 8,500.00 (ca. $9,300). Digitized versions can be downloaded in low (9 MB) and very high (600 MB) res from archive dot org.

Turn back the clock

Another trip around the sun provides an opportunity to remember the recent anniversaries of notable events in Jerusalem’s history:

The city’s railway was inaugurated on September 26, 1892. Some remarkable early video footage was taken from a train departing the Jerusalem station in 1897.

Charles Wilson reached Jerusalem to begin the Ordnance Survey on Oct 2, 1864. I wrote a short entry about benchmarks etched in Jerusalem’s walls during this survey.

On Oct 12, 1923, Robert Macalister and J. Garrow Duncan began their excavations in a plot of cauliflowers on the Southeastern Hill. They revealed the top of a monument now known in archaeological literature as the Stepped Stone Structure. I wrote about this consequential dig that began 101 years ago in two parts.

A great fire broke out in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher on Oct 12, 1808, causing extensive damage.

Reflections

I recently came across this springtime photo which shows part of the scarp of Mount Precipice (Jebel al-Qafzeh) on the southern outskirts of Nazareth. Grasses and wildflowers grow between jagged bedrock outcroppings. The limited pockets of soil trapped in cracks and rock depressions provide a sufficient context for these plants to survive. Their roots in turn make the soil more resistant to erosion.

Though far from Jerusalem, the topography of this scene in Nazareth reminded me of discussions about the Gennath Gate (“Garden Gate”). This gate, mentioned only by Josephus, was located somewhere on the northern part of the Western Hill in Jerusalem. It features heavily in contemporary discussions about the Tomb of Jesus and the authenticity of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

In a post exploring the location of this gate, I surveyed ideas about the nature of the presumed garden located outside this gate and near a stone quarry. One view, mentioned by Justin Kelley in his book on the Holy Sepulcher, is that this garden could have been cultivated within pockets of soil that sat between exposed bedrock in the quarry (Kelley 201972n14). Although no quarry is present, this photo nonetheless conveys the sense of a natural green space set within exposed limestone which can be used to illustrate Kelley’s suggestion about the garden in Jerusalem.

Upcoming Events

November 11-12 in Jerusalem: A two-day conference commemorating the 1300th anniversary of Willibald’s arrival in Jerusalem. Day one will be hosted at Dormition Abbey and feature lectures by a number of scholars, as well as ecumenical prayers and liturgies. Day two includes site visits to the Sepulcher, St. Anne’s Church, Mary’s Tomb, and Gethsemane. These events are free and open to the public. Contact Rodney Aist (coursedirector@sgcjerusalem.org) or Georg Röwekamp for more details (g.roewekamp@dvhl.de).

Paid Supporters

Thanks to all who attended the recent livestream. We discussed:

The context of Nahman Avigad's excavations in the modern Jewish Quarter after 1967 and their ongoing publication

A new preliminary report about the excavations at Birket al-Hamra ("The Red Pool"), widely believed to be the ancient Pool of Siloam

The next livestream is scheduled for December 10 from 8:00-9:30pm ET. Paid supporters will receive a private link beforehand. They also gain access to the archive of previous livestream events, among other benefits.

Milestones

This newsletter recently surpassed 600 subscribers. I’d like to offer my gratitude to all of you, especially those who have shared and supported the effort.

Ehud Netzer wrote that the Antonia Fortress was "probably the first building erected by Herod in Jerusalem, and apparently one of the first constructed by him throughout his kingdom" (2006:120).

“Did Herod build the foundations of the Western Wall?” by Eli Shukron in City of David - Studies of Ancient Jerusalem. 7 (2012). Though widely cited, the publications of this annual conference are available in only in selected libraries. Most are not digitized or even available for purchase.

This also has a bearing on the common assumption that the so-called temple cleansing of Jesus took place in the Royal Portico, as the structure would have had to be completed beforehand.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee. Less than 1% of readers do this, and it makes an enormous difference.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View the newsletter archive and follow Approaching Jerusalem on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.

City of David Studies back copies are now available in the City of David store onsite and there is currently a sale.