Jerusalem in Brief (No. 9)

New Year greeting, early photos of the Mount of Olives, the Mosque of the Ascension, and a book on childhood in Jerusalem

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription and receive unique Jerusalem-related benefits.

Happy new year! In 2025, my goal is to continue publishing two posts a month, on the second and final Fridays. I found this to be a generally achievable writing pace last year. Occasionally my schedule is too hectic to meet this goal due to family needs, dissertation writing, or other work. I always regret when this happens and make every effort to avoid it.

The first post published each month will be a new edition of the Jerusalem in Brief, covering several short topics about the city. Typically, I like to write about the visualization of Jerusalem, either in a historical photograph, map, model, or other illustration (“Jerusalem visualized”). When relevant I will also write about books or other Jerusalem-related material that I have recently acquired (“New arrivals”). I also enjoy sharing interesting excerpts from books I’m reading (“Notes and quotes”) or fun Jerusalem-related things I’ve found online (“Internet standout”). I try as well to link to upcoming in-person or online events about Jerusalem as they are available (“Upcoming events”).

These and some other categories will appear in each Jerusalem in Brief depending on what I encounter during reading and research. Sometimes the content of these posts stays within the bounds of the same historical period. Other times, the view is wider, and each category of the post covers a different time period and quite divergent topics. Whichever periods or subjects in Jerusalem’s history you are most interested in, my hope is that you will find something valuable.

The second post of the month on the final Friday is meant to be a longer-format discussion about one issue. For instance, last year, I explored whether a group of 8th-century BCE houses underneath a large fortification wall (“Avigad’s Wall”) in the modern Jewish Quarter could be related to a text in Isaiah 22, as many scholars have claimed. I also looked at some issues in the travelogue of William Bartlett, an English sketch artist who visited Jerusalem in the summer of 1842 and wrote a lament over modern Mount Zion.

The Jerusalem Tracker publications will also arrive in your inbox on the last Friday of every month. These are quarterly posts that I generally send in February, June, August, and November. They are my best attempt to list every new academic publication about historical Jerusalem. I also link to helpful digital resources (videos, podcasts, etc), important stories in popular media, and descriptions of new developments in Jerusalem that are relevant to the historical city. So far, I have published nine of these lists dating back to September 2022, and the archive is free and available to peruse.

I currently follow over 250 periodicals, 80 book publishers, and a number of social media and popular outlets in search of relevant material. Last year, I listed 26 new books, 169 academic articles, and over 200 media stories and resources about historical Jerusalem, along with a number of new local developments and upcoming events. These posts are my best attempt to follow the wide array of material that is relevant to understanding and appreciating the history of Jerusalem. Whatever your specific interests, I’m certain you will find something relevant in these lists.

I mean it sincerely when I say: thank you for reading this newsletter. I’m grateful for your interest in the history of Jerusalem and to have you as a subscriber. If you have benefitted from this publication and want to support its continued publication, consider upgrading to a paid subscription or simply leaving a small one-time token of gratitude. Sharing newsletter posts also helps a lot, whether on social media or by forwarding them along to friends, family, or colleagues who may find them interesting.

And now, enjoy the regular content of the Jerusalem in Brief.

Jerusalem visualized

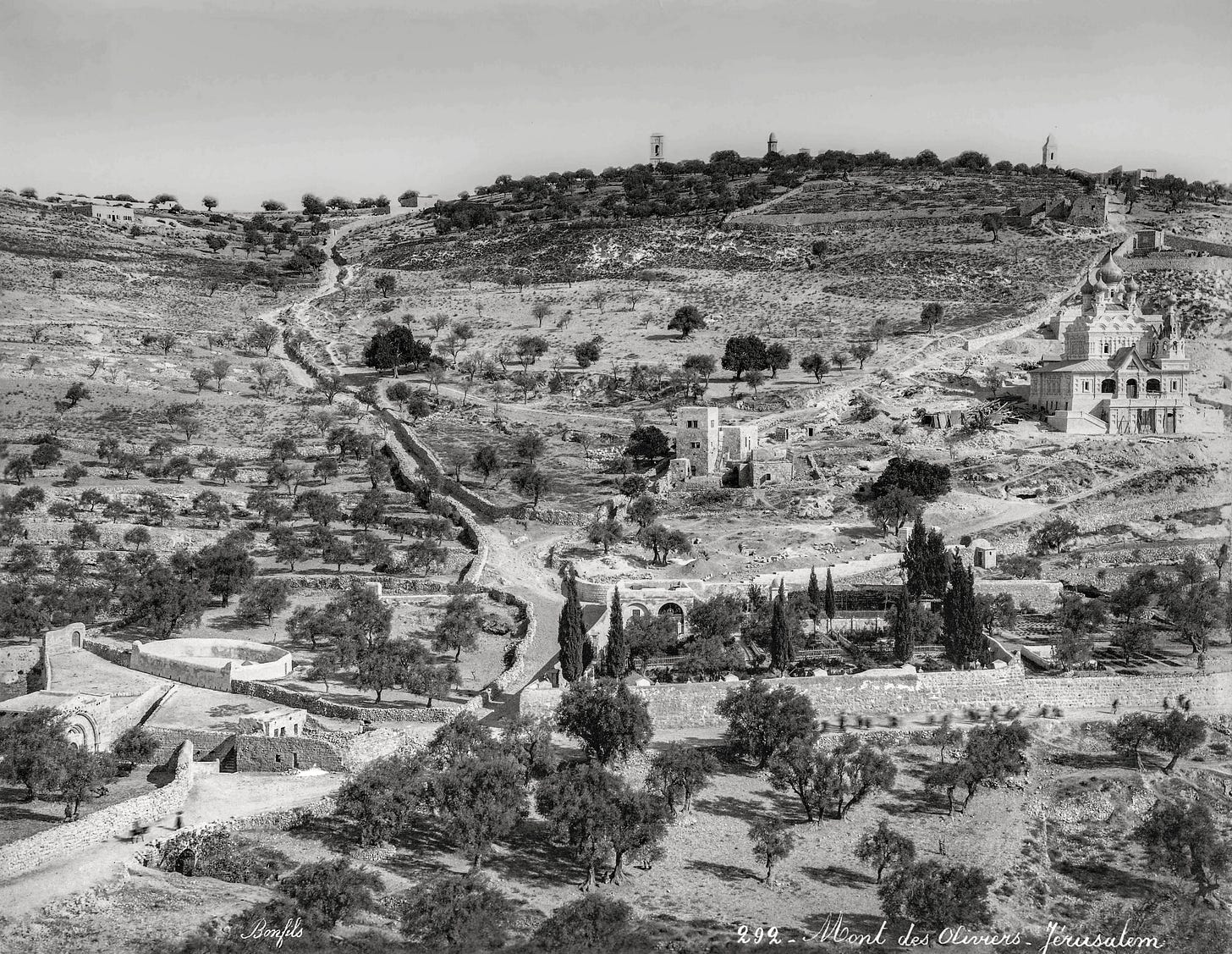

The two historical photos below show virtually identical angles of the central Mount of Olives nearly three decades apart. The top photo was taken by Francis Frith, I believe sometime in the late 1850s. The exact date of the bottom photo is something of a mystery to me for reasons I’ll get into below, but it seems to have been captured in the mid-late 1880s.

The later photo clearly shows the onion-domed Russian Orthodox Church of Mary Magdalene (center right), which was completed in 1888. It is signed “Bonfils” on the bottom left side. The well-known photographer Félix Bonfils passed away in 1885, suggesting he may not have taken the photo. Perhaps his wife Lydie or their son Adrien, both of whom were also photographers, took the photo on a trip to Jerusalem after his death (Gibson 2003:173). Alternatively, as some scaffolding can be seen around the Church of Mary Magdalene, perhaps the building had not been completed when the photo was taken. If that was the case, it may date a few years prior, perhaps to 1885 or earlier when Félix Bonfils was still alive. In this scenario, and assuming he took a trip to Jerusalem late in his life (I have no idea whether he did), he may have taken the photo himself.

Both photos feature important sites on the slopes of the mountain. The traditional Garden of Gethsemane, with its olive trees walled in by a stone fence, sits near the center. The entrance to the Crusader-era Tomb of Mary can be seen on the far left. On the skyline at the top of the mountain, the photos show part of the minaret above the Mosque of the Ascension.

The roughly three decades between these photos reveals new construction that took place during that time. I have already mentioned the Church of Mary Magdalene, with its golden onion-shaped domes, which is absent from the top photo but appears in the bottom one. Some new construction within the traditional Garden of Gethsemane can also be seen, as well as around the tower that stands behind it. The later photo also shows three distinct built projections on top of the mountain, as opposed to only the minaret of the Mosque of the Ascension in the earlier one. The tower on the right is from the Church of the Pater Noster, which was completed in 1872 (Murphy-O’Connor 2008:144). The bell tower furthest to the left belongs to the Russian Orthodox Church of the Ascension.

The seemingly half-built bell tower of the Church of the Ascension is another puzzling aspect of this photo. This tower was completed and fitted with a bell in 1885, three years prior to the completion of the onion-domed Church of Mary Magdalene. Yet, the Church of Mary Magdalene appears near complete and the bell tower only partially complete. Perhaps both building were under construction when the photo was taken, which would help date it prior to 1885 as I suggested above. If this was the case, it is a rare shot of both structures prior to their completion. On the other hand, it may be that the tower of the Church of the Ascension had already been completed when the photo was taken, and this part of the photo was damaged. The level nature of the bell tower as it appears in the photo makes me think the first option is more likely.

The time gap between the photos is also shown by the huge difference in tree growth. As best I can tell, the majority of the trees on the mountain are olive trees, both in hillside terraces, in the garden of Gethsemane, and at the base of the photo in the Kidron Valley (Wadi en-Nar). The distinctly pointed conifers inside the fence of Gethsemane are cypress trees. A comparison of the two photos shows that appreciable growth of these trees occurred during these decades. Today the cypress trees have been removed from Gethsemane, but many were planted in the areas behind it and are now quite tall.

Several roads can be seen in both photos, all of which are paved streets today. Three turn to the south (right), running middle, high, and low. The middle of these roads is the one used by tour groups who view Jerusalem from the lookout near the Seven Arches Hotel and then descend to the Garden of Gethsemane below. The street at the bottom of the photos runs along the stone fence built around traditional Gethsemane. Today this area is a sidewalk, and a two-lane road was later constructed west of it. The remaining two roads fork and then wind their way to the top of the mountain.

Among other things, these photos remind us of the many churches and holy sites in Jerusalem that were established at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. Several more were built between the time when these photos were taken and our own day, including the teardrop-shaped Dominus Flevit (1955) and the Church of All Nations (1924). During this time, the sacred topography of Jerusalem was impacted by a huge wave of construction that has contributed to the city we experience today.

Notes & quotes

In his book Jerusalem 1900: The Holy City in the Age of Possibilities, Vincent Lemire devotes a chapter to the creation of holy sites in Jerusalem during the 19th and 20th centuries (see my review of the book here). We have seen physical evidence of such construction in the photos above. Many of these new holy sites reflect elements of separatism, whether religious or nationalistic. However, Lemire argues that an examination of Jerusalem’s pre-19th century sacred geography suggests instead a sense of integration. He notes, for instance, the Cenacle/King David’s Tomb building, which has served as a church, mosque, and synagogue (73-74). The reality of all three can be seen in the building’s architecture. He also discusses the Mosque of the Ascension, which contains the footprint of Jesus, evoking a connection with the footprint of Muhammed enshrined across the valley in the Dome of the Rock. He continues:

“Today, even though the Mosque of the Ascension is located just a few steps away from the most popular sites on the Mount of Olives, it is nearly deserted. The site seems neutralized, as if it had been “demonetized.” This hybrid holy site, uncertain, opened to original porosities that in the past linked the various religious traditions of Jerusalem, no longer corresponds to pilgrims’ expectations of solidly established markers with impermeable limits—the sort of markers needed to reaffirm their beliefs and respective identities in a largely secularized social environment. A small mosque, bare and unpretentious, with a mihrab turned toward Mecca and bearing the footprint of the prophet Jesus, is an admirable symbol of the syncretism of “the people of Jerusalem.” It is a confusing, uncomfortable place for a European, African, or Asian pilgrim of today, who has come to Jerusalem to strengthen his or her own spiritual practice and not to weaken it through contact with disquieting composites. The extraordinary growth of pilgrimages to the holy land since the end of the nineteenth century ultimately appears to be a determining factor in explaining the polarization and the differentiation of the traditions linked to Jerusalem’s holy sites. The accumulation of these exogenous gazes, seeking clear and well-marked identities, largely explains this development” (73).

To my mind, engaging with Jerusalem’s modern sacred landscape requires fostering a spirit of curiosity and appreciation, whatever the background of the visitor or nature of holy sites that one may encounter.

Recent arrivals

Several books were waiting for me under the Christmas tree this year, including Child in Jerusalem by Felicity Ashbee (Syracuse University Press). She has also written a biography of her mother Janet. Felicity is the daughter of Charles Robert Ashbee who was an architect appointed as Civic Advisor at the beginning of the British Mandate Period (Crawford 1985:178). Felicity lived in the city from 1919-1923, spanning ages six to ten. A short perusal of the book shows that it contains narrative retellings of her childhood in Jerusalem. She describes interactions with people and visits to places across the city. The forward, written by H. V. F. Winstone describes the book’s point of view as a “delightfully naive rendering of infant wonderment” (xi). I’m happy to add this unique voice about Jerusalem to my bookshelf and look forward to reading it.

In case you missed it

My last post in 2024 listed some notable contributions to Jerusalem’s history last year. The list includes a variety of material from new books to individual studies and social media projects. I also included some honorable mentions of contributions from years prior.

Paid Supporters

The next livestream is scheduled for March 11 from 8:00-9:30pm ET. Paid supporters will receive a private link beforehand.

During these events, I discuss excavations, publications, pop media articles, and developments relevant to historical Jerusalem. I also share resources and occasionally present original research. Participants will have the opportunity to ask questions. Paid subscribers get access these quarterly events and the archive of previous recordings.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee. Less than 1% of readers do this, and it makes an enormous difference.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View the newsletter archive and follow Approaching Jerusalem on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.

I love seeing those two photos side by side! And a really interesting discussion of possible dating for the second one. Thanks!