An Orientation on the Jerusalem Skyline

Elevated structures along the edges of Jerusalem's historic basin help us find our bearings as we navigate the city.

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

One way this newsletter seeks to contribute to the study of Jerusalem is by applying the city’s physical setting to discussions about its past. Engaging with Jerusalem’s topography grounds our historical pursuits and helps to limit interpretations and possibilities. It also provides connective tissue that binds source material together meaningfully, whether it emerges from a text or was unearthed in a localized excavation.

Becoming familiar with Jerusalem’s geography requires intentionality, curiosity, and mindful observation. This certainly assumes the exploration of new areas in the city, but even short walks along familiar routes are opportunities to engage in these beneficial practices. The placement and details of masonry, angle of streets, dips and rises on the landscape, or patches of jarringly flat topography can all contribute to our understanding of the city’s historical development if we become aware of and internalize them.

Navigating the higher-level geography in Jerusalem is aided by existing structures on the horizon that can act as points of orientation. The city has scores of recognizable landmarks like the Dome of the Rock, Old City wall, Dormition Abbey Church, or the Tower of David. However, these are not always visible from every (or even most) vantage point(s). In this post I want to detail some of the highest, most distinctive, and easily visible structures on the rim of Jerusalem’s historic basin. I’ve tried my best to select buildings that sit on the cardinal points, although that isn’t always possible.

East: Three Towers on the Mount of Olives

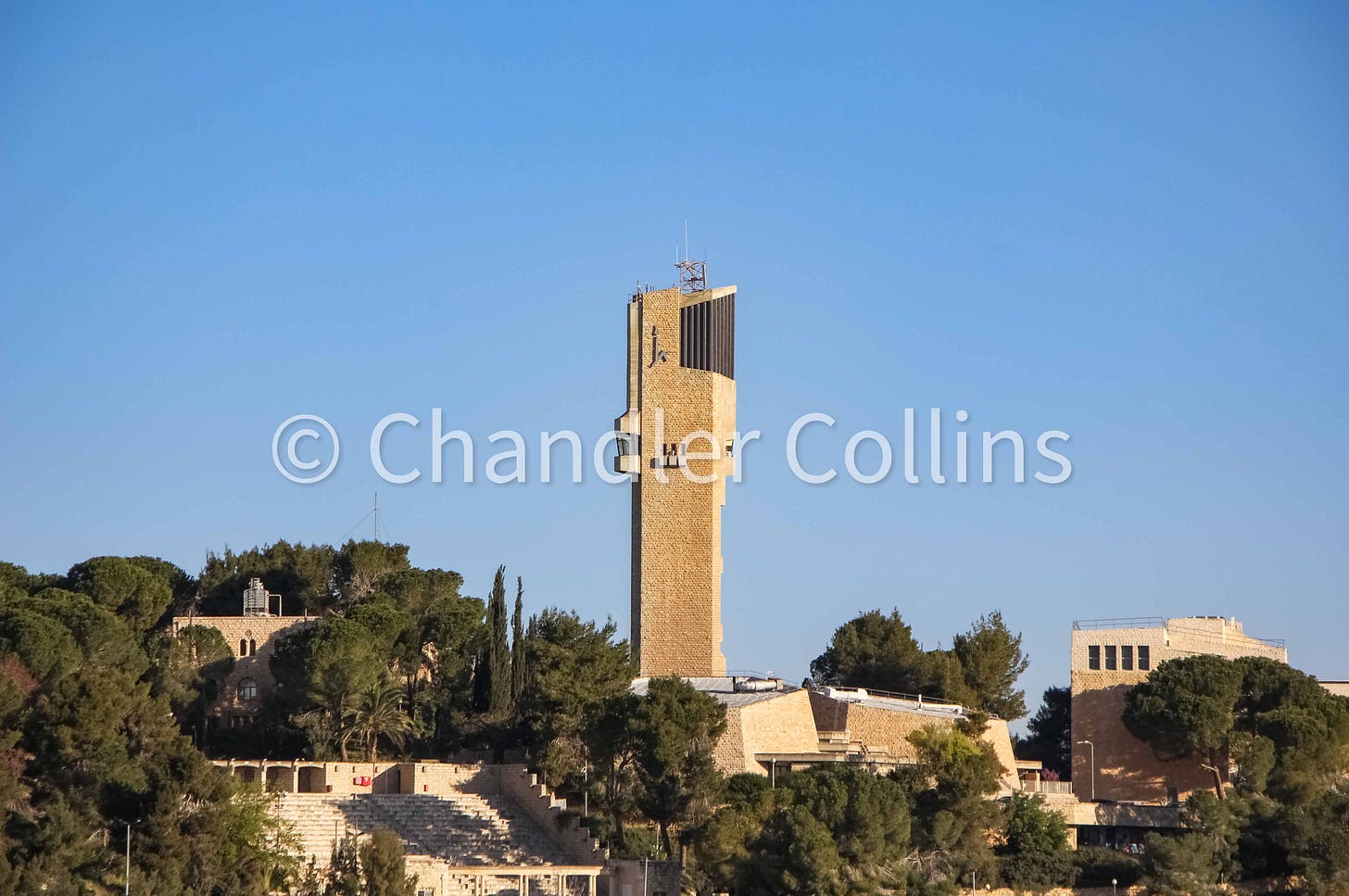

Perhaps the best known and most easily identifiable landmark on the east side of the historic basin is the Mount of Olives ridge and its three tall towers. From north to south, these include the water tower on the Hebrew University campus, and the bell towers in the Augusta Victoria complex and Russian Orthodox Church of the Ascension. The ridge and its towers can be seen at some distance, even from Transjordan on a clear day. If you can identify this ridge on the horizon, you will know with certainty that the Old City lies on its west side.

Learning to identify the details of each tower can be helpful if the mountain is partially obscured. While the Hebrew University water tower can appear somewhat rounded from a distance, the more southerly two are square with pointed roofs. Dark, fluted material on the eastern section of the water tower also sets it apart from the others. An antenna that once topped it has been dismantled in advance of renovations that will transform the tower into an observatory with several accessible glass floors and an observatory providing views from the Dead Sea to the Mediterranean on a very clear day.

Although the central and southern towers on the Mount of Olives are both square shaped, several differences make them easily distinguishable from each other. The bell tower at the Augusta Victoria has a larger base, making it appear more bulky. It is also topped with a squatty, dark roof. By contrast, the Russian Church’s bell tower appears more slender and has a narrow, pointed, and more lightly colored roof. There are also evenly spaced windows at each level, while the only openings on Augusta Victoria’s tower are near the top.

West: City Tower

We might reason that the YMCA tower is the most natural and unique orientation point on Jerusalem’s west side. However, I have found that it can be easily obscured behind the King David Hotel or other buildings depending on the angle. A taller landmark is preferable. Situated more deeply in West Jerusalem, City Tower is not only 21 stories, but also has the advantage of standing on a plateau with an elevation similar to the Russian Compound. Its height, blocky shape, and tall antenna, make it an excellent candidate to serve as a western landmark.

The value of City Tower is not only that it indicates a general western direction, which is obvious enough from the new construction and cranes on this part of the skyline. It also allows us to specifically pinpoint the heart of West Jerusalem using only the horizon. City Tower is fixed between Zion Square and Machane Yehuda Market, just above the intersection between Ben-Yehuda St. and King George St. This location is nearly a straight shot from the northwest corner of the Old City wall. It is worth walking between the two points to internalize the distance and follow changes in the topography.

South: Twin Apartment Buildings in Talpiot/Arnona

The isolation and symmetry of two apartment buildings make them the perfect southern reference point on Jerusalem’s horizon. The buildings sit in the Talpiot/Arnona neighborhood on the east side of Hebron Road which leads toward Bethlehem. They also helpfully mark the southerly extension of the Watershed Ridge, a continuous crest that divides surface rainwater flow alternatively east or west in the Jerusalem hills.

Northern Options

Unlike other directionals, the urban sprawl north of Jerusalem lacks a singular and unique landmark. Perhaps historical or municipal processes have prevented the construction of such a building here. The lower-lying and relatively even topography is another factor. These same physical characteristics made Jerusalem’s northern portion the city’s historical weak point.

From certain vantage points looking north, Nebi Samwil will be visible on the far horizon. Other distinctive buildings are unfortunately adjacent to the corners of the Old City wall rather than in the center, and they are not consistently visible. The Rockefeller Museum across from the northeast corner of the Old City provides a good northern reference from some angles but is obscured in others.

Other distinctive buildings are located at the northwest corner of the Old City, including the Notre Dame Hotel, with its crenelated towers and statue of the Virgin Mary with Jesus, and the tower of the Italian Hospital building nearby. Across the road from Notre Dame and inside the Old City stands the bell tower of Saint Saviour’s monastery. Its height and isolation probably make it the most readily identifiable of all the northern landmarks mentioned here, although it sits more to the northwest.

Learning to identify mainstays of the Jerusalem skyline will give students of the city helpful tools to orient themselves from open spaces, on rooftops, or when catching pieces of the horizon between Old City buildings. Since most landmarks described here are visible both inside and outside of the historic basin, they can also help to build geographic connections between Jerusalem and its hinterland. The city is an ever-evolving landscape, and future buildings may serve as better points of orientation on the horizon. In the meantime, I introduce this handful to my students and benefit from knowing them myself as I traverse the city. Perhaps they will help you as well.

What landmarks do you use to orient yourself in Jerusalem?

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous editions of this newsletter or follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.