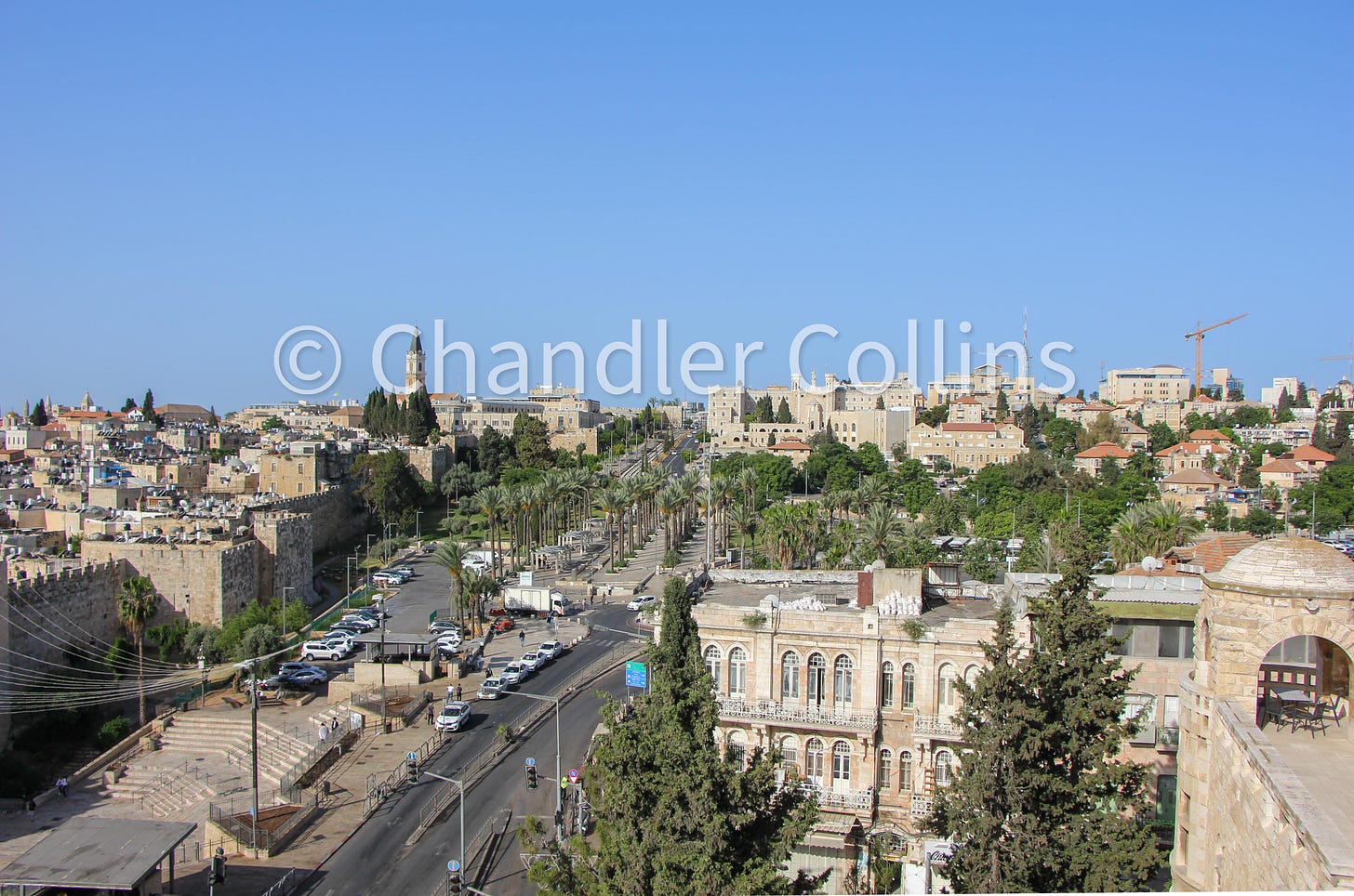

Getting to know the "Russian Compound Plateau"

The strategic plateau northwest of the Old City has played key roles in Jerusalem's historical development. It is also home to surprising archaeological remains.

If you find this newsletter valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription

Most discussion about Jerusalem’s topography understandably focuses on the city’s major hills and valleys, but smaller geographical elements like saddles, slopes, dips and ascents, and even manmade features have impacted the city’s development in important ways. Today’s newsletter is an introduction to one small element of Jerusalem’s topography northwest of the Old City walls that I have termed “The Russian Compound Plateau.”

The plateau seems to be more known than visited. Tourists and pilgrims are generally preoccupied with sites located within the historic basin further south. Besides a trip to City Hall to pay arnona (property tax) or a similarly exciting activity, there is little to draw most residents to the top of the Russian Compound. Jaffa Street provides a convenient bypass around it to the post office, Machane Yehuda Market, or the sea of cafes with outdoor tables lining both sides of the road.

Topographically, the Russian Compound Plateau represents the extension of a ridge that runs northwestward from the Jaffa Gate area. Several previous iterations of Jerusalem’s walls, including the current Ottoman wall, have been built upon this ridge. Thousands of pedestrians walk along a key part of it every day when they cross to Jaffa Street from the area of New Gate, where the light rail train bends at the northwest corner of the Old City wall. The Russian Compound Plateau is the strategic high point of this ridge, sitting near 2600 feet above sea level. Travelers walking to the Russian Compound from Jaffa Gate will feel the slow ascent as they go, especially along the Old City walls, and again in the final push to the top of the plateau.

Making the Russian Compound

The elevated plateau was purchased by the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission, and a compound to house Russian pilgrims was built in the early 1860s. In his memoirs, the Palestinian Jerusalemite and oud player Wasif Jawhariyyeh lists the Arab families of Lifta who previously owned the plot where the Russian Compound was built (pg. 79). He also gives an interesting description of the buildings, the Russian pilgrims, and the industry that sprang up along the nearby streets to serve them (pgs. 79-82).

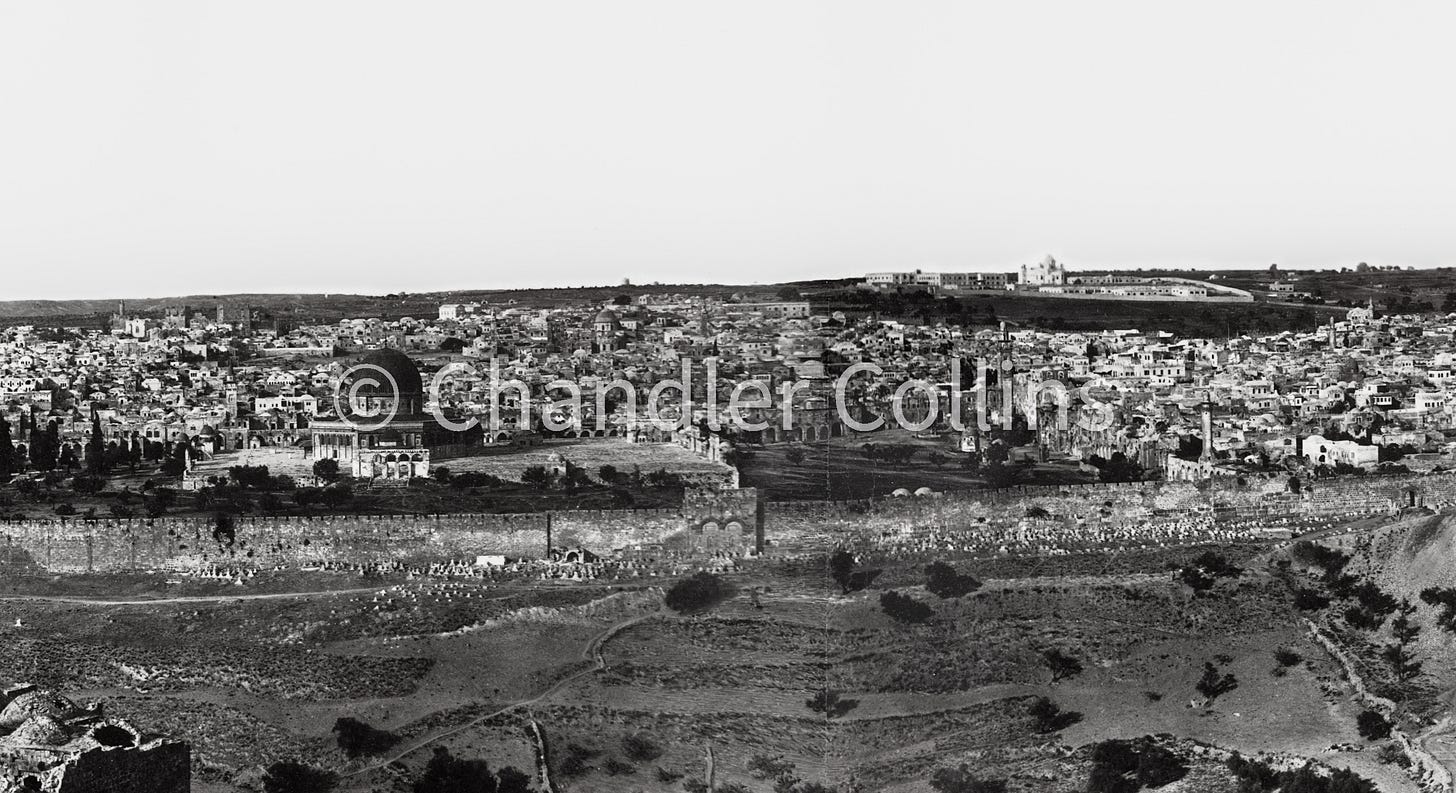

The need for these pilgrims to access Christian holy places in the Old City was one factor that led to the opening of New Gate in 1887. Because the Russian Compound was constructed along the main thoroughfare that brought travelers to the city from the coast, it altered previous first views of Jerusalem in which the walled city was set against the bare landscape. Travelers who visited in the mid-late 19th century were confronted with these and other changes springing up around the city.

Archaeological goodies

Several significant archaeological finds have been unearthed on the Russian Compound Plateau. One of the first to be excavated was a huge monolithic pillar that was found during work in front of the Russian Cathedral in 1871. The pillar presumably broke during the quarrying process and was discarded by the ancient masons. Its dating is not certain archaeologically. Charles Clermont-Ganneau, who saw the pillar as it was being excavated, originally believed that it had been destined for use in the Royal Stoa on the Herodian Temple Mount. A sign posted nearby the pillar today still reflects this interpretation. It is also possible that it was hewn for use in a later period.

Excavations on the Russian Compound Plateau have also contributed to our knowledge of the Third Wall, Jerusalem’s northern fortification in the late first century CE. Josephus famously described this wall in his book The War of the Jews, but no potential piece of its western line had been identified in a controlled excavation until 2015 when a salvage dig took place in the area of the new campus for the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. A 13-meter stretch of what seems to be the Third Wall was uncovered, along with a tower and evidence of a battle that appears to have taken place during the Roman assault on Jerusalem in 70 CE (Arbiv 2023).1

In his description of the Third Wall, Josephus states that its western line began at the tower Hippicus (almost certainly the Tower of David) and ran north to another tower called Psephinus. He includes a short description of Psephinus:

“Now the third wall was all of it wonderful; yet was the tower Psephinus elevated above it at the north-west corner, and there Titus pitched his own tent; for being seventy cubits high it both afforded a prospect of Arabia at sun-rising, as well as it did of the utmost limits of the Hebrew possessions at the sea westward. Moreover, it was an octagon, and over against it was the tower Hippicus…” (War V.161)

The location of Psephinus is not certain, and no possible remains of it have been recovered as far as I know. But most scholars place it in the area of the Russian Compound where the geography would allow it to be, in Josephus’s words, “elevated above” the Third Wall. From a tall enough building on this high plateau, it might have been possible to see both Transjordan (“Arabia”) and the Mediterranean Sea on clear days. Josephus may also, of course, be exaggerating the view for his readers.

Getting to the Russian Compound is easy from any direction. It is worth a visit to appreciate the geographical setting, the buildings of the Russian Compound—vestiges of 19th-century Russian imperialism in Ottoman Palestine—and the “Finger of Og.”

The excavation also yielded a mass grave, possibly victims of a massacre during the reign of Hasmonean King Alexander Jannaeus. Other excavations nearby have uncovered remains from Russian building activity in the 19th century preceding the Russian compound.

Enjoy this post?

Show your appreciation by leaving a tip as low as the price of a cup of coffee.

Follow Approaching Jerusalem

View previous editions of this newsletter or follow us on social media for archaeological stories, upcoming lectures, and other Jerusalem-related news, resources, and analysis.